-

How does it feel?

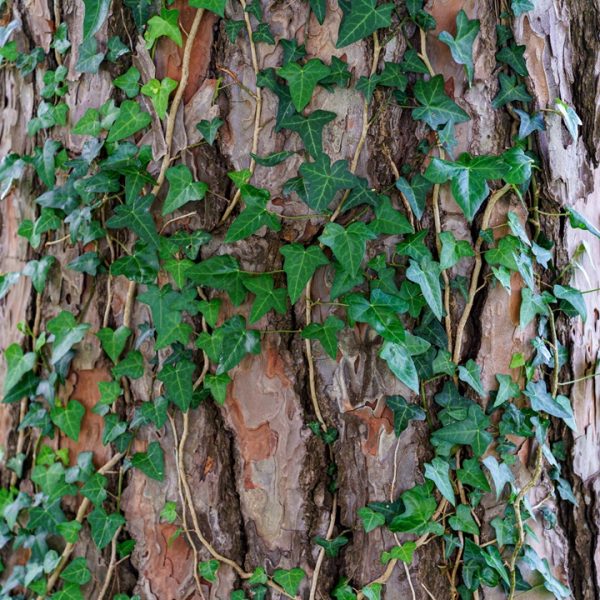

Ivy is perhaps one of the most common plants to be found in the UK. It can cover whole forest floors, trees, walls or buildings. One of the only native, evergreen flowering plants, it is incredibly resilient to all weather, sun or shade and grows on a variety of soils. As such, it might not often be noticed, and just form part of the green wall, when out in nature. Its leaves are dark green, with lighter coloured veins and can bring even in the darkest and coldest of winter, a sense of life and hope for spring.

Indeed in ancient times, this plant was seen as a symbol for immortality, fidelity and resilience. It was traditionally used for wedding ceremonies, as a symbol for the strength of the union, of the ones to be betrothed. The flowers are delicate and tend to bloom late in the year — offering vital pollen to bees in times when most flowers have perished. On a warm autumn day, one can often hear the hum of bees within an ivy thicket. But there is also something dark about its nature.

Neither the leaves, with their leathery texture nor the dark berries (which are toxic) seem very inviting to be gathered for eating or to be made into a brew, signalling to stay away. Perhaps it is also the fact that it can often be found on graveyards and old decaying buildings — a constant reminder of our impermanence — in contrast to its own seaming immortality.

-

What can I use it for?

Whilst this herb doesn’t seem to be very popular with the modern herbalist in the UK, it has a long history of medicinal use, as well as modern research. In some countries such as Germany and Poland, ivy leaf cough syrups are readily available over the counter in modern pharmacies (1).

Its main indications are for the respiratory system, where it is used as an expectorant for conditions associated with productive coughs, including asthma, upper respiratory tract infections and bronchitis (1,2,3). It acts as a bronchodilator, antispasmodic and by watering down thick mucus (4).

-

Into the heart of common ivy

Ivy (Hederay helix) Ivy makes an appearance in various ancient cultures, as it can be commonly found across Northern Africa, Asia and Europe. In ancient Egypt ivy was associated with the Osiris, god of the underworld, and who represented immortality and life after death. In ancient Greece ivy was sacred to the Greek god Dionysus, the god of wine, pleasure, and celebration. He was often depicted with an ivy crown and staff, and myths connect the plant to his divine birth and his life.

It was believed that ivy could protect someone from the negative side effects of getting drunk. The Romans had a similar association with their god of wine Bacchus, and it became tradition to hang ivy above tavern doors to signal a good quality drink, and the metaphor of ivy embracing a tree was used as a symbol for marriage. In christianity, ivy became a commonly found symbol for both faithfulness and eternal life (5).

In Geradd’s Herbal it explores ivy’s energetic qualities, which seem to be contradicting in nature, as it has both cooling, as well as heating qualities. While it is green and fresh, it contains an earthy, cold, binding nature, which, upon drying, becomes hot and biting (6).

-

Traditional uses

Ivy (Hederay helix) The traditional use of ivy is rooted in European herbal medicine where the leaves, rather than the berries, have been employed most consistently as a remedy for respiratory conditions and certain topical complaints. However, in the past the berry was also used in various ways.

According to Culpepper, the berries used to be used for treating jaundice and parasitic worms, and were seen as a preventative and remedy for the plague. Interestingly, the berries had different uses depending on their level of ripeness. Taken in wine, they were also used as a diuretic and to stimulate menstruation. Fresh ivy leaves were boiled in vinegar and applied externally to ease stitches, aches, and headaches. Fresh leaves boiled in wine were applied to infected wounds and burns and the juice of fresh berries or leaves were applied to ulcers (7). Externally, ivy was also used to treat ringworm and other skin conditions.

Another remedy mentioned is the use of young ivy shoots, extracted in butter, which is applied to the skin to aid with sunburn (8).

For more than a century ivy leaf extracts have been prepared as teas, syrups and standardised dry or liquid extracts used to relieve productive coughs by loosening mucus and facilitating expectoration. This clinical application is reflected in modern regulatory assessments and monographs, such as the European Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products that describe ivy leaf as an expectorant for bronchitic and cough-associated mucus production (2).

Phytochemically, the therapeutic activity is often attributed to triterpenoid saponins (notably hederacoside C and related glycosides) that reduce mucus viscosity and exhibit mild antispasmodic and bronchodilator effects on bronchial smooth muscle; additional anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial actions have also been reported in preclinical and clinical literature. These pharmacological findings support the longstanding use of ivy in productive coughs (9).

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

Western actions

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

Chinese energetics

Western energetics

-

What practitioners say

Respiratory

RespiratoryToday, ivy leaf is best known and understood as a remedy for chest ailments — especially for productive coughs, bronchitis and other conditions involving mucus-laden airways (1,2). It is used both for chronic conditions, such as asthma, but also acute conditions such as upper respiratory infections or bronchitis, and its use is considered safe for children from two years of age onwards (2). To understand the medicinal actions of ivy, much research has focused on the saponins present in the plant.

The saponins of Hedera helix have been extensively studied; especially α-hederin and hederacoside C have been in the focus of research. α-hederin in particular has been shown to increase the production of surfactant in the lungs, leading to a decreased mucus viscosity, as well as to increased bronchodilation and decreased spasm of the bronchi musculature (10). However, other phytochemicals present, such as the dicaffeoylquinic acids and flavonol derivatives also contribute to ivy’s overall antispasmodic effects (11). The saponins also showed anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial and antioxidant effects but often they were extracted and used in much higher concentrations than present in the leaves, which makes it difficult to use these results when talking about the whole plant extracts (11).

Musculoskeletal

Ivy has traditionally been used to treat rheumatism. The herb can be taken internally, or applied externally, directly on the affected joints. A decoction of fresh leaves (200 g/l water) may be used externally for rheumatism or a poultice can be made by mixing fresh Hedera helix leaves with linseed meal at a 1 to 3 ratio (11).

Research into the anti-arthitic effects of Hedera helix is restricted, but shows initial promising results (12,13). One study compared an ivy-gel with placebo and with diclofenac gel (NSAID) for the treatment of osteoarthitis of the knee in 150 patients. It found that the ivy-gel significantly reduced morning stiffness, daytime stiffness, and physical function compared to the placebo group (14).

Skin

Hedera helix has been used for various skin conditions in the past, and indeed is seen as an effective treatment for cellulite and also having wound healing properties (11). Note, that the fresh herb can cause allergic reactions on the skin due to its falcarinol content (11). With potential skin irritants, it is always advised to conduct a patch test first, and discontinue treatment, should any irritation skin occur.

-

Research

Ivy (Hederay helix) Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and wound-healing properties of the methanolic extracts from Hedera helix fruits and leaves

The study evaluated methanol extracts from fruits and leaves of Hedera helix (ivy) for antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and wound-healing effects. The fruit extract had slightly higher total phenolic content (100 GAE mg/g) than leaf extract (≈89.5 GAE mg/g), while the leaf extract had higher flavonoid (≈37.1 TE mg/g) and tannin (≈24.8 GAE mg/g) levels. Antioxidant tests (DPPH, ABTS, FRAP) showed both extracts neutralise free radicals, with fruit extract stronger in DPPH/FRAP and leaf extract slightly better in ABTS.

In an in vitro assay of albumin denaturation — a marker of inflammation — the leaf extract inhibited denaturation more effectively than the fruit extract, suggesting a higher anti-inflammatory potential.

In a rat skin-wound model, ointments made with the extracts significantly accelerated wound-closure compared to a plain ointment: By day 12, wounds treated with leaf-extract ointment had the greatest contraction (~95.8%), indicating enhanced healing. Overall, the study provides evidence that ivy leaf and fruit extracts exert antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and wound-healing effects — supporting traditional uses and potential for topical therapeutic applications (15).

Unveiling the antibacterial and antioxidant potential of Hedera helix leaf extracts: Recent findings

In this study the authors prepared an ethanolic extract from ivy leaves and measured its chemical composition, antioxidant capacity and antibacterial activity.

The extract was rich in phenolic compounds (≈134.3 mg gallic-acid equivalents /g) and flavonoids (≈42.4 mg catechin equivalents /g).

In laboratory assays, the extract showed substantial antioxidant activity — in the DPPH assay it inhibited ~65% of free radicals (at 80 µg/ml) and in the FRAP assay showed a reducing power of ~9.5 mmol Fe²⁺ /g dry weight.

As for antibacterial effects, the ivy-leaf extract inhibited the growth of two respiratory-relevant pathogens: Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumoniae — showing zones of inhibition of ~23.2 mm and ~18.5 mm, respectively. However, it did not inhibit Escherichia coli or Pseudomonas aeruginosa under the test conditions.

The study provides evidence that ivy-leaf ethanolic extract has both antioxidant and selective antibacterial properties, supporting its potential for combating oxidative stress and some bacterial infections — including possibly respiratory pathogens — though further research is needed to further understand these implications (16).

-

Did you know?

Ivy (Hederay helix) Ivy is commonly seen as a type of weed, which can strangulate trees, take over gardens or damage buildings. And whilst ivy can indeed damage trees and buildings, it is not as all or nothing as it seems.

Ivy doesn’t strangulate trees. It is not parasitic to trees either and doesn’t damage healthy trees. However, if a tree is already weakened and has a very light canopy, then ivy can grow all the way into the crown and shade out the already sparse leaves of the tree it grows on. In this way, it can then outcompete the tree for light.

Ivy roots cannot penetrate sound masonry, however if cracks and holes are already present, then the roots may penetrate them and enlarge them as the root grows in diameter. Additionally ivy can lift up roof tiles, if it isn’t regularly managed. If left to grow unmanaged, ivy can indeed cause damage to buildings, particularly if they are old or have damp issues. On the flipside, it has been shown that ivy can increase the insulation efficiency of buildings, ivy covered walls being 1.4°C warmer throughout the night and 1.7°C cooler during the middle of the day, than walls not covered in ivy (17,18). In summary, if left to grow unmanaged, ivy can indeed cause damage to buildings, but if managed well, it may well improve insulation.

Ivy provides shelter and food for countless animals, including insects, mammals, and birds. The leaves provide shelter year round making it a favourite nesting and hibernation plant for many animals. Its leaves are a food source to many caterpillars of native butterflies, and are also grazed by fallow, roe and red deer in deepest winter, when little else is available. Sheep also love grazing on ivy (perhaps for its anthelmintic effects) (19). Ivy typically flowers late in the year (September) and thus provides a great source of pollen and nectar at a time when little else is around.

Analysis of honey bees in the autumn showed that 89% of all pollen in the sampled hives consisted of ivy pollen and bees also gathered a high proportion of ivy nectar (20). Taxa of insects foraging on ivy included honey bees (21%), bumble bees (Bombus spp., 3%), ivy bees (Colletes hederae, 3%), common wasps (Vespula vulgaris, 13%), hover flies (Syrphidae, 27%), other flies (29%) and butterflies (4%) (20). The berries are a vital food source for birds throughout the winter. Perhaps unsurprising for such a common plant — many animal species rely on it in various ways for their survival.

Additional information

-

Botanical description

Ivy is an evergreen, woody climbing plant, often found on trees or walls, but it can also be found crawling over the ground. As a climbing vine, H. helix uses specialised aerial rootlets to adhere to surfaces, allowing it to occupy vertical spaces and compete effectively for light.

Round, branching twigs with dark green, 3–5-lobed leaves grow out of the stem that holds onto the supporting surface with tiny roots. The leathery leaves, glossy on the upper surface and with light-colored veins, are winter hardy. Leaves on flower bearing twigs tend to have an oval to lance-shaped appearance. The plant only develops little umbels of flowers when it is 8–10 years old, it propagates mainly vegetatively. The flowers develop quite late in the year, flowering from September to October, ripening into berries the following year. The berries turn from a light green colour to a purple/black colour when ripe (25).

-

Common names

- Common ivy

- English ivy

-

Safety

Safety during pregnancy and lactation has not been established. In the absence of sufficient data, the use during pregnancy and lactation is not recommended (2).

Contact with fresh leaves or plant juice of ivy may lead to sensitisation and then a delayed hypersensitivity reaction or allergic contact dermatitis. This is due to the presence of falacrinol in the plant. People, such as gardeners, who commonly handle the fresh plant would be best advised to wear protective equipment such as gloves, when handling it (21).

If using ivy topically, conduct a patch test first and do not continue treatment if any undesired side effects such a rash occur.

In large quantities, ivy leaves can provoke nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and excitation (22).

The use of ivy within the therapeutic range has been shown to be generally well tolerated and safe for children (over two years of age and with adjusted dosages), as well as the elderly (22).

-

Interactions

None known (2)

-

Contraindications

- Caution is advised in people with gastritis or gastric ulcers (2).

- Ivy is also contraindicated in children under the age of two (2).

-

Preparations

- Ivy leaf macerated in vinegar used as a mouthwash for toothache (23).

- A decoction of fresh leaves (200 g/l water) may be used externally for rheumatism (11).

-

Dosage

Information on dosage is varied within the literature. Preparations studied all rely on different extraction ratios and forms, making it difficult to extrapolate to more traditional tinctures. Adult doses tend to range to dried herb equivalent doses of 250–420 mg of dried herb and are most commonly 300 mg daily (22). If one had a traditional 1:5 ratio tincture this would be the equivalent of 1.5 ml daily.

-

Plant parts used

Dried leaf, collected in spring (22)

-

Constituents

- Triterpene saponins (2.5–6%): Derivatives of hederagenin, oleanolic acid, bayogenin. Hederagenin is an aglycone (without sugar). Glycones (With sugar) of hederagenin are: hederacoside C (1.7–4.8%), hederacoside D (0.4–0.8%), hederacoside B (0.1–0.2%), α-hederin (0.1–0.3%), hederagenin being the aglycone part of most of these saponins (24).

- Flavonoids: Quercetin, kaempferol, rutin, astragalin

- Coumarines (scopolin)

- Phenolic acids: Caffeic acid, rosmarinic acid, p-coumaric acid, 3,5-O-dicaffeoyl-quinic acid, chlorogenic acid

- Polyacetylenes: Falcarinone and falcarinol are both commonly occurring polyacetylenes found in carrot, parsley and ginseng (Eleutherococcus senticosus), and acts as a natural antifungal for the plant. It can cause allergic reactions in sensitive individuals (22,24).

- Volatile oils: (in the fresh leaves 0.1–0.3%) Consists of methylethyl ketone, methyl isobutyl ketone, trans-hexanal, germacrene D, ß-caryphyllene, sabinene, α- and ß-pinene (22)

- Sterols: Stigmasterol or its C‐24 isomer, poriferasterol, is the main component, and lesser amounts of sitosterol, α‐spinasterol, 5α‐stigmast‐7‐en‐3β‐ol, cholesterol, and campesterol (24).

- Alkaloid: Emetin — the presence of this alkaloid in the leaf is disputed (22).

- Vitamins E, C, pro-vitamin A (24)

-

Habitat

Ivy is native to much of Europe and Western Asia, where it thrives across a wide range of climates and ecological conditions. Its natural distribution extends from the British Isles and Scandinavia in the north, across Central and Southern Europe, and into the Caucasus and parts of the Middle East. This broad native range reflects the species’ remarkable adaptability and resilience.

Ivy typically grows in temperate woodlands, forest edges, and shaded hedgerows, where it benefits from cool, moist soils and protection from intense sunlight. It can be found carpeting the forest floor, climbing tree trunks, or scrambling over rocks and old stone structures.

Beyond its native range, Hedera helix has been widely introduced as an ornamental plant and has naturalised in many regions, including North America, Australia, and parts of East Asia. In some of these areas, it has become invasive, flourishing especially in mild, moist coastal climates. Despite this, in its native habitats it plays a valuable ecological role, offering shelter and late-season nectar to various wildlife species (26).

-

Sustainability

There are currently no threats to the species Hedera helix. Due to its wide geographical occurrence and its ability to thrive in various climates and ecological conditions, ivy plant populations are very stable and often considered invasive (26,27,28).

Habitat loss and over-harvesting from the wild are two of the biggest threats faced by medicinal plant species. There are an increasing number of well-known herbal medicines at risk of extinction. We must, therefore, ensure that we source our medicines with sustainability in mind.

The herb supplement industry is growing at a rapid rate and until recent years a vast majority of medicinal plant produce in global trade was of unknown origin. There are some very real and urgent issues surrounding sustainability in the herb industry. These include environmental factors that affect the medicinal viability of herbs, the safety of the habitats that they are taken from, as well as the welfare of workers in the trade.

The botanical supply chain efforts for improved visibility (transparency and traceability) into verifiably sustainable production sites around the world is now certificated through the emergence of credible international voluntary sustainability standards (VSS).

Read our article on Herbal quality & safety: What to know before you buy and Sustainable sourcing of herbs to learn more about what to look for and questions to ask suppliers about sustainability.

-

Quality control

Herbal medicines are often very safe to take, however, it is important to buy herbal medicines from a reputed supplier. Sometimes herbs bought from disreputable sources are contaminated, adulterated or substituted with incorrect plant matter.

Some important markers for quality to look for would be to look for certified organic labelling, ensuring that the correct scientific/botanical name is used and that suppliers can provide information about the source of ingredients used in the product.

A supplier should be able to tell you where the herbs have come from. There is more space for contamination and adulteration when the supply chain is unknown.

-

How to grow

Ivy is an easy-to-grow, versatile plant that thrives in a range of conditions, making it suitable for both indoor and outdoor cultivation. It prefers bright, indirect light but can tolerate shade, especially outdoors where it naturally grows beneath tree canopies.

Plant ivy in well-drained, moderately fertile soil, and keep the soil consistently moist but not waterlogged. Regular watering during dry spells helps maintain lush growth, while allowing the top layer of soil to dry slightly between waterings prevents root rot. Be aware that it can easily overtake your garden, and before planting any outside, make sure it is already native in your area, as in some parts of the world it is considered an invasive species (7).

-

References

- Sierocinski E, Holzinger F, Chenot JF. Ivy leaf (Hedera helix) for acute upper respiratory tract infections: an updated systematic review. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. Published online February 1, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-021-03090-4

- European Medicines Agency. European Union Herbal Monograph on Hedera Helix L., Folium.; 2017.

- Sierocinski E, Holzinger F, Chenot JF. Ivy leaf (Hedera helix) for acute upper respiratory tract infections: an updated systematic review. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. Published online February 1, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-021-03090-4

- European Medicines Agency. Ivy Leaf.; 2017.

- Artefacts-Collector Ivy – A Symbol of Eternal Life, Fidelity, and Resilience, accessed via https://artefacts-collector.com/ivy/#:~:text=Historical%20Origins%20of%20the%20Ivy,symbols%2C%20especially%20in%20funerary%20contexts. On 27/11/2025

- Gerard J. Gerard’s Herbal – Part 3, CHAP. 316. Of Ivy.

- Culpepper N. 1642 The Complete Herbal. Accessed via http://www.complete-herbal.com/culpepper/ivy.htm on 27/11/2025

- Grieve M. 1971 A Modern Herbal. Accessed via https://www.botanical.com/botanical/mgmh/i/ivycom15.html on 27/11/2025

- Baharara H, Moghadam AT, Sahebkar A, Emami SA, Tayebi T, Mohammadpour AH. The Effects of Ivy (Hedera helix) on Respiratory Problems and Cough in Humans: A Review. Natural Products and Human Diseases. Published online 2021:361-376. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-73234-9_23

- Pourová J, Dias P, Pour M, et al. Proposed mechanisms of action of herbal drugs and their biologically active constituents in the treatment of coughs: an overview. PeerJ. 2023;11:e16096-e16096. :https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.16096

- Lutsenko Y, Bylka W, Matławska I, Darmohray R. Hedera helix as a medicinal plant. Herba Polonica. Published 2018. Accessed December 12, 2025. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Hedera-helix-as-a-medicinal-plant-Lutsenko-Bylka/0f38cf404822fe200cb69c42a3a9dd067503369c

- Al-jaafreh AM. Anti-inflammatory, Antioxidant, and Wound-healing Properties of the Methanolic Extracts from Hedera helix Fruits and Leaves. Biomedical and Pharmacology Journal. 2024;17(2):1091-1102. https://doi.org/10.13005/bpj/2925

- Qabaha K, Abbadi J, Yaghmour R, Hijawi T, Naser SA, Al-Rimawi F. Unveiling the antibacterial and antioxidant potential of Hedera helix leaf extracts: recent findings. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 2023;102(01):26-32. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjpp-2023-0264

- Shokry AA, El-Shiekh RA, Kamel G, Bakr AF, Sabry D, Ramadan A. Anti-arthritic activity of the flavonoids fraction of ivy leaves (Hedera helix L.) standardized extract in adjuvant induced arthritis model in rats in relation to its metabolite profile using LC/MS. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & Pharmacotherapie. 2022;145:112456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112456

- Rai A. The Antiinflammatory and Antiarthritic Properties of Ethanol Extract of Hedera helix. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2013;75(1):99. https://doi.org/10.4103/0250-474x.113537

- Dehghan M, Saffari M, Rafieian-kopaei M, Ahmadi A, Lorigooini Z. Comparison of the effect of topical Hedera helix L. extract gel to diclofenac gel in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Journal of Herbal Medicine. 2020;22:100350-100350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hermed.2020.100350

- Bolton C, Rahman MA, Armson D, Ennos AR. Effectiveness of an ivy covering at insulating a building against the cold in Manchester, U.K: A preliminary investigation. Building and Environment. 2014;80:32-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2014.05.020

- The RHS Advice Team, 2025. Ivy on buildings and fences Accessed via https://www.rhs.org.uk/prevention-protection/ivy-on-buildings on the 01/12/2025.

- METCALFE DJ. Hedera helix L. Journal of Ecology. 2005;93(3):632-648. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2005.01021.x

- Garbuzov M, Ratnieks FLW. Ivy: an underappreciated key resource to flower-visiting insects in autumn. Leather SR, Roubik D, eds. Insect Conservation and Diversity. 2013;7(1):91-102. https://doi.org/10.1111/icad.12033

- Ozdemir C, Schneider LA, Hinrichs R, et al. [Allergic contact dermatitis to common ivy (Hedera helix L.)]. Der Hautarzt; Zeitschrift Fur Dermatologie, Venerologie, Und Verwandte Gebiete. 2003;54(10):966-969. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00105-003-0584-4

- European Medicines Agency. Assessment Report on Hedera Helix L., Folium.; 2017.

- Barker J. 2001. The Medicinal Flora of Britain and Northwestern Europe.

- Lutsenko Y., Bylka W., Matlawska I., Darmohray R. 2010 Hedera Helix as a Medicinal Plant.

- Royal Botanical Gardens Kew. Ivy – Hedera helix | Kew. Kew.org. Published 2024. https://www.kew.org/plants/common-ivy

- Emerine S. Hedera helix (ivy). CABI Compendium. 2022;CABI Compendium. https://doi.org/10.1079/cabicompendium.26694

- IUCN Redlist. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Published 2025. Accessed December 12, 2025. https://www.iucnredlist.org/search?taxonomies=106667&searchType=species

- Blinkova O, Rawlik K, Jagodziński AM. Effects of limiting environmental conditions on functional traits of Hedera helix L. vegetative shoots. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2024;15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2024.1464006

- RHS. Hedera (ivy) / RHS Gardening. www.rhs.org.uk. https://www.rhs.org.uk/plants/ivy/growing-guide