-

How does it feel?

Turmeric has a powerful earthy, rich and aromatic distinctive flavour. Upon tasting, the first impression is of a very powerful aromatic spice, quickly turning into a taste similar to black pepper. This is followed by a significant bitterness, followed by a second wave of heat and finally a lingering aromatic and warming aftertaste.

The warming effects on the body can be felt almost immediately after tasting, with a specific effect felt on the digestive system, which then spreads throughout the body.

-

What can I use it for?

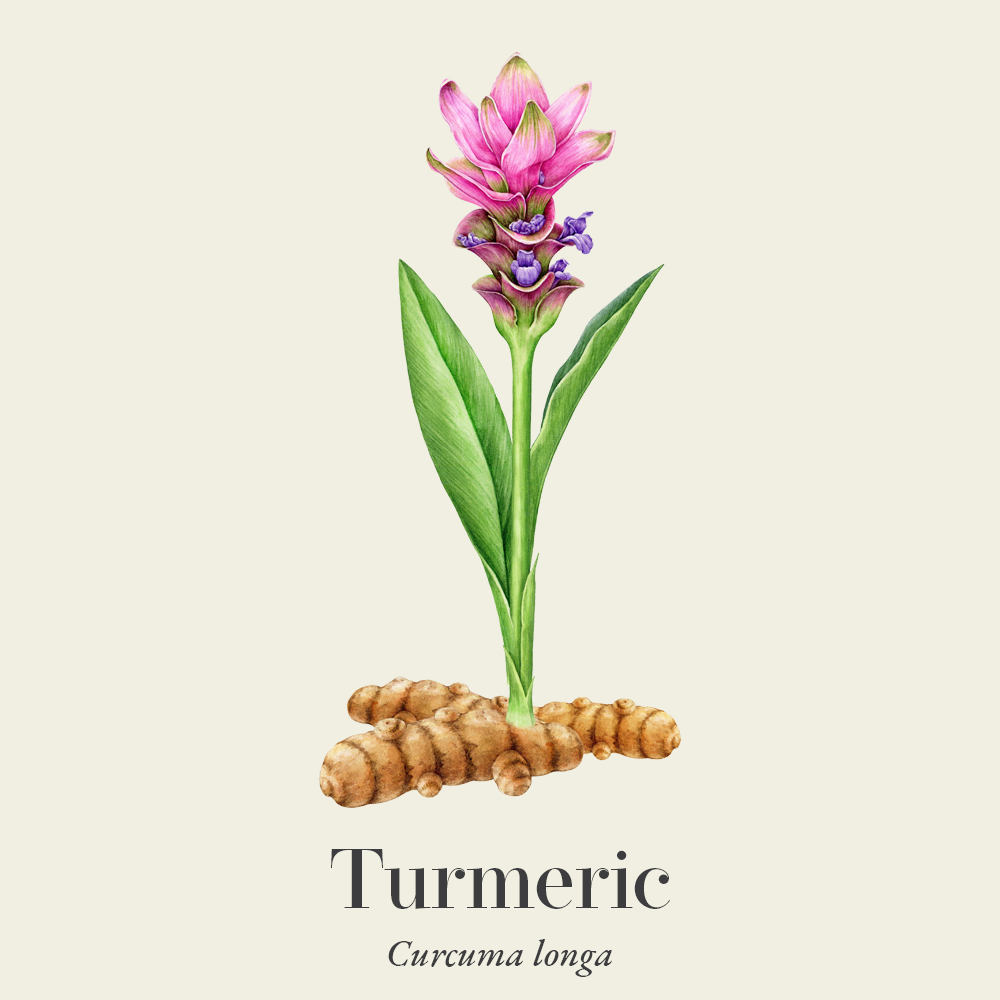

Turmeric (Curcuma longa) Turmeric can be included in a daily routine to help support long term inflammatory conditions including skin and joint problems, such as arthritis and other rheumatoid conditions. Turmeric is often consumed in regular daily quantities in India as part of a balanced diet incorporated into cooking.

Turmeric has an affinity for the digestive system, and is known to ignite agni (digestive fire) within Ayurvedic medicine. Its anti-inflammatory properties act directly on the digestive system, helping to treat chronic inflammatory conditions originating in the gut including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s. Many chronic inflammatory diseases are linked to inflammation in the gut and intestinal barrier dysfunction, and in such cases turmeric can support positive treatment outcomes (1). T

Turmeric has wider benefits on gut health and due to its prebiotic properties, and can help in building a healthy gut microbiome (2). It can be taken after a course of antibiotic treatment or to help in recovery from a debilitating illness to aid recovery and support the regrowth of a healthy microbiota. It has also been shown to reduce symptoms of indigestion and IBS (3,4).

Turmeric is a hepatic and helps to stimulate bile flow, which supports the body in detoxification from drugs, alcohol and toxins (5). It is advisable to source turmeric from reputable sources and pay attention to recommended dosages to reduce the risk of liver injury. It contains high levels of antioxidants, which have shown to reduce oxidative stress and increase free radical scavenging potential.

Turmeric is a warming, drying spice in the same category as ginger (Zingiber officinale) (to which it is related), black pepper (Piper nigrum) and chillies (Capsicum minimum). Turmeric can be called upon when symptoms are worsened by cold, damp conditions which is often the case with arthritic problems.

Turmeric is helpful in relieving a variety of menstrual conditions, including in cases of pelvic inflammation and stagnation, bloating and in instances where symptoms are relieved with a hot water bottle. Turmeric’s anti-inflammatory actions help to increase circulation and provide warmth, thereby helping to alleviate pain in the pelvic area (5).

-

Into the heart of turmeric

A key concept in Ayurvedic health is that of supporting agni (fire) in digestion, as a metaphor for all digestive and metabolic processes at the core of health. It relates to the Ayurvedic term ãma — the idea that an accumulation of toxins in the digestive system can lead to problems elsewhere in the body.

Turmeric is known as deepana — enkindling the digestive fire, and pachana — helping digestion. This may be the most powerful image for understanding the benefits of turmeric.

-

Traditional uses

Turmeric (Curcuma longa) Turmeric has been one of the most valued remedies in Ayurvedic medicine, as a heating and drying remedy that moves the circulation, and clears digestive-based toxins (ãma or damp) especially from the lower abdomen and pelvic areas. This ties in closely with the Ayurvedic concept of supporting agni (fire) in the digestion.

Turmeric has a long list of traditional health uses across many cultures. In India, it is regarded as a stomachic, tonic and blood purifier and used for poor digestion, fevers, skin conditions, vomiting in pregnancy and liver disorders. Externally, it is applied for conjunctivitis, skin infections, cancer, sprains, arthritis, haemorrhoids and eczema.Another common use is to promote wound healing (6).

In traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), different applications are attributed to the rhizome and tuber. Turmeric rhizome is said to be a blood and qi tonic with analgesic properties. It is used to treat chest and abdominal pain and distension, jaundice, frozen shoulder, amenorrhoea due to blood stasis and postpartum abdominal pain due to stasis. It is also applied to wounds to disinfect and accelerate wound healing. The tuber has similar properties, but is used in hot conditions as it is considered to be more cooling. One particular application is viral hepatitis (6,7).

Traditional Thai medicinal uses include for gastrointestinal ulcers, anal haemorrhage, vaginal haemorrhage, skin disease, ringworm, insect bites and to prevent the common cold. In earlier Western herbal medicine, turmeric was regarded as an aromatic digestive stimulant and as a cure for jaundice (6).

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

Western actions

Ayurvedic actions

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

Ayurvedic energetics

-

What practitioners say

Digestive system

Digestive systemTurmeric has widespread application to digestive problems. As a very widely consumed culinary spice it has long been favoured for reducing indigestion in many forms, including dyspepsia, colic and IBS. It can help to restore a disturbed microbiome and can be considered in many inflammatory bowel diseases and even as part of a bowel cancer support regime (6).

Turmeric has a stimulant effect on the liver, increasing bile output and helping to dissolve and prevent gallstones. It is traditionally considered a blood purifier and is often used for promoting clear skin and clearing systemic toxaemia; eczema, urticaria, psoriasis and acne (6,7).

Reproductive system

In Ayurvedic terms turmeric is used to clear kapha accumulations from the lower abdomen, uterus and apanakshetra. This is specific for treatment of fibroids, cysts, endometriosis, dysmenorrhoea, amenorrhoea and congestive pelvic inflammatory conditions and unusual vaginal discharge. As a specific herb for rasa dhatu it also works on the secondary tissue stanyasrotas and is used to purify breast milk as well as to promote the flow of the menses.

Immune system

Turmeric is known to reduce systemic inflammation. It is used in arthritic problems, dermatitis, and other skin problems. In Ayurveda it is favoured for pitta-kapha conditions and in this case mixed with more bitter herbs.

Cardiovascular system

Turmeric has circulatory stimulating and warming properties similar to ginger, chillies or black pepper. This leads to increased blood flow through the tissues, and is likely to accentuate its value in treating inflammatory conditions that are worsened by the cold (5).

Integumentary system

Turmeric is excellent for reducing pain as a topical application in bruises, infections, swellings as well as for inflammations like mastitis, sprains and pain. Caution is advised as it is a powerful dye and will stain everything it comes into contact with.

-

Research

Turmeric essential oil (Curcuma longa) Curcumin is the main constituent in turmeric responsible for many of its therapeutic actions, however it is insoluble in water, and rapidly converted to inactive metabolites in the gut, so is in fact poorly absorbed into the tissues (8). Studies have shown that potentially only 1% of curcumin consumed is absorbed through the gut wall and into the body (9). One review of more than 120 clinical trials found no successful double blind, placebo controlled trial of curcumin, and concluded that it is an unstable, reactive, non bioavailable compound(4).

Fortunately, as one author has reported “curcumin does not need to be absorbed to bring about its effects since it has profound effects on the intestinal wall and can effectively reduce inflammation by this mechanism” (10). The following summary identifies research that follows the action of both curcumin and other turmeric constituents on the gut wall.

Chili peppers, curcumins, and prebiotics in gastrointestinal health and disease

Curcumin has been shown to reduce the activity of gut wall proinflammatory factors, including cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), 5-lipoxygenase (LOX), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), TNF-a, IL-1, -2, -6, -8 and -12, TLR 4, and Nf-kappa-β (11).

Curcumin improves intestinal barrier function: Modulation of intracellular signaling, and organization of tight junctions

An in vitro study using human intestinal epithelial cell (IEC) lines (Caco-2 and HT-29) and macrophages was carried out to analyse the effects of curcumin on LPS-induced inflammation and barrier dysfunction. Curcumin was administered at 5 μM for 48 hours and the results showed curcumin successfully reduced LPS-induced inflammatory signalling and preserved tight junction integrity. The study suggested that turmeric can be used to treat metabolic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, resulting from diet-induced gut barrier dysfunction (12).

Curcumin-mediated regulation of intestinal barrier function: The mechanism underlying its beneficial effects

A review carried out amongst preclinical studies and human trials found that curcumin acts locally in the gut due to poor systemic availability. It concluded there were a number of different mechanisms of action including: Preserving the mucus layer, reducing direct bacterial contact with epithelial cells; enhancing tight junction protein (e.g., ZO-1, claudins) expression and organisation thereby reducing paracellular permeability and gut bacteria-derived lipopolysaccharide (LPS) translocation and by increasing secretion of antimicrobial peptides. The study found positive outcomes in the treatment of metabolic, inflammatory, and neurological diseases including obesity, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, depression, and arthritis (13).

Curcumin as a therapeutic agent in the chemoprevention of inflammatory bowel disease

A systematic review and meta-analysis was carried out to examine placebo-controlled randomised clinical trials (RCTs) on curcumin in treating inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including both ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). Thirteen RCTs were included with curcumin being administered orally and compared to placebo across a range of dosages. The results showed a significant improvement in UC patients achieving remission in, with adverse effects being similar between placebo and curcumin groups. No clear benefit was found for Crohn’s disease, however it concluded that turmeric is an effective anti-inflammatory and gut protective herb to use in treating UC (14).

Comparison of remicade to curcumin for the treatment of Crohn’s disease: A systematic review

A systematic review was carried out amongst peer reviewed human studies after 2007 to evaluate the effect of curcumin as a treatment in conjunction with remicade amongst patients with Crohn’s disease (CD). It found that patients using curcumin saw an average reduction of 55 points in the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) and improved inflammatory markers (15).

Effect of different curcumin dosages on human gall bladder

A randomised, single-blind, three-phase, crossover clinical trial was carried out amongst healthy human volunteers to explore the effect of curcumin on gallbladder contraction. Curcumin was administered orally to 12 healthy volunteers at dosages of 20 mg, 40 mg and 80 mg, with each participant receiving all three doses in different phases. Results showed 40 mg of oral curcumin was sufficient to induce a 50% contraction of the gallbladder within two hours in participants (16).

There are also other powerful constituents of turmeric that are likely to be more easily absorbed and have their own significant activity elsewhere in the body (17). Particular interest has been in ar-turmerone which, as well as being readily bioavailable, has shown to have promising anti-inflammatory, anti-angiogenic and neurorestorative properties (18,19,20,21). Given the current interest in the inflammatory aetiology of mental health problems and neural disease, it is of interest that turmeric has been identified to play a role in modulating microglial inflammation (22).

-

Did you know?

The reason turmeric is called turmeric is because it is considered a blessing of the earth from the Latin ‘terra merita’.

In Chinese Herbal Medicine turmeric (jiang huang) is taken as a decocted tea and in Ayurveda turmeric (haridra) is often taken with other oils and spices.

Additional information

-

Botanical description

It is a tall, stemless herb that can grow up to 1.5 m in height and has characteristic large, pale green and elongated leaves. Turmeric flowers are a pale yellow colour. The root (technically rhizome) is oblong or cylindrical and often short-branched. The external colour of the rhizome is brown and internally the colour ranges from yellow to bright yellow-orange.

The rhizome consists of two parts: An egg-shaped primary rhizome and several cylindrical and branched secondary rhizomes growing from the primary rhizome. These two parts were once differentiated in the Western trade as C. rotunda and C. longa. In traditional Chinese medicine, this differentiation is retained, the primary rhizome being called the ‘tuber’ and the secondary rhizome, the ‘rhizome’ (27).

-

Common names

- Indian saffron (Eng)

- Kurkumawurzelstock (Ger)

- Gelbwurzel (Ger)

- Rhizome de curcuma (Fr)

- Safran des Indes (Fr)

- Haridra (Sanskrit)

- Haldi (Hindi)

- Jianghuang (Chin)

-

Safety

Large medicinal doses should be avoided during pregnancy (5).

-

Interactions

Owing to turmeric’s antioxidant qualities, it is posited that turmeric may attenuate the effects of alkylating agents used as chemotherapy. There has also been research to suggest that turmeric may reduce the concentration of tamoxifen (23).

Turmeric also has potential additive effects with anticoagulant drugs, such as warfarin, methotrexate, and amlodipine (23).

For anyone taking any medications wishing to work with herbs, working under the guidance of a herbal practitioner is always advised.

-

Contraindications

Contraindicated with duodenal and gastric ulcers, gallstones and biliary tract obstruction (5).

-

Preparations

- Fresh rhizome

- Dried powdered

- Capsules

- Tincture

-

Dosage

- Tincture (ratio 1:3| 60%): Take between 3–15 ml in a little water per day.

- Dried powdered or capsule: 4 g or a heaped teaspoon of powdered turmeric (or equivalent preparation) 1 to 2 times daily (24)

-

Plant parts used

Root (rhizome)

-

Constituents

- Terpenoids

- Monoterpenes: α-pinene, β-pinene, limonene, p-cymene, α-terpineol

- Sesquiterpenes: Ar-turmerone, bisabolene, curcumene, germacrone, γ-atlantone, curcumenol, turmerone

- Triterpenes: Phytosterols (campesterol, stigmasterol, β-sitosterol)

- Curcuminoids: Yellow pigments (3–6 %), (diarylheptanoids and diarylpentanoids), 22 identified including curcumin (diferuloylmethane) and demethoxylated curcumins.

- Phenolic compounds: Caffeic acid, protocatechuic acid, coumaric acid, coumarins, phenylpropanoids

- Carotenoids: β-Carotene

- Polysaccharides: Arabinose

- Essential oil (2.5 to 5%) containing sesquiterpene bisabalones (including ar-turmerone 28%, β-turmerone 17% and curlone 14%), zingiberene, phellandrene, sabinene, cineole, borneol

- Vitamins and minerals: Vitamin C, calcium, phosphorous, potassium, sodium, magnesium, iron, zinc, manganese, chromium, cobalt, nickel, copper

Turmeric’s most prominent active constituent curcumin is generally referred to as if it was a single chemical entity. However, it is actually a variable mixture of three diarylheptanoids: diferuloylmethane (curcumin I), desmethoxycurcumin (curcumin II), and bisdesmethoxycurcumin (curcumin III). Sample-to-sample variability of curcuminsignificantly reduces the consistency of research findings for its effects and bioavailability (25,26).

- Terpenoids

-

Habitat

Turmeric originated in south Asia, in particular India, but it is cultivated in many warm tropical regions of the world where it is found to have naturalised. It is no longer found in its native habitats however, its native habitat would be humid warm climes with a lot of rainfall (26).

-

Sustainability

Not currently on risk lists but complete data may be missing on the status of the species. Read more in our sustainability guide. According to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Plants Status this species is currently classed as data deficient, meaning it has not been assessed. It is occasionally found to have naturalised in places where cultivation takes place. Further research would be needed to understand its conservation needs (28). Turmeric is widely cultivated to meet growing consumer demand (29).

Habitat loss and over-harvesting from the wild are two of the biggest threats faced by medicinal plant species. There are an increasing number of well-known herbal medicines at risk of extinction. We must, therefore, ensure that we source our medicines with sustainability in mind.

The herb supplement industry is growing at a rapid rate and until recent years a vast majority of medicinal plant produce in global trade was of unknown origin. There are some very real and urgent issues surrounding sustainability in the herb industry. These include environmental factors that affect the medicinal viability of herbs, the safety of the habitats that they are taken from, as well as the welfare of workers in the trade.

The botanical supply chain efforts for improved visibility (transparency and traceability) into verifiably sustainable production sites around the world is now certificated through the emergence of credible international voluntary sustainability standards (VSS).

Read our article on Herbal quality & safety: What to know before you buy and Sustainable sourcing of herbs to learn more about what to look for and questions to ask suppliers about sustainability.

-

Quality control

Turmeric provides a clear example of how important it is to ensure the quality of the herbs purchased over the counter. Research into why pregnant women in rural Bangladesh had high levels of lead revealed that it was linked to turmeric intake (30).

Turmeric in Bangladesh was contaminated with lead, from a paint dye added to improve the colour. Apparently brighter, more vibrantly coloured turmeric is considered to be better quality and sells for a higher price. This practice of colouring the turmeric was initiated in the 1980s after a poor harvest which was mouldy, to disguise the brown colour of the poor-quality turmeric. Whilst manufacturers were not necessarily aware of the health risks involved in this, the practice was not reviewed and continued for almost 40 years until these investigations revealed the source of lead intake, and was presented to government, agriculture and food industry representatives (30).

This is a cautionary tale to ensure the quality and traceability of supply chain when buying herbs, and preferably to buy herbs from reputable suppliers.

Herbal medicines are often very safe to take; however, their safety and efficacy can be jeopardised by quality issues. So, it is important to buy herbal medicines from a reputable supplier, from sources known to test their herbs to ensure there is no contamination, adulteration or substitution with incorrect plant matter, as well as ensuring that recognised marker compounds are at appropriate levels in the herbs.

Some important quality assurances to look for are certified organic labelling, the correct scientific/botanical name, and the availability of information from the supplier about ingredient origins. A supplier should be able to tell you where the herbs have come from, what contaminants are not in the herb, and what the primary compounds are.

-

How to grow

Turmeric plants are fairly easy to grow indoors in a planter or container. They need plenty of warmth and sunlight to replicate the growing conditions of their native habitat.

You will need a 14–18-inch pot or planter for each six to eight inches of rhizome, and enough potting soil to fill it. To start, you can sprout your turmeric rhizome in a smaller container to be transplanted later into the larger containers (usually once they have a few leaves).

You can purchase a store bought turmeric rhizome. Cutting into sections, with two or three buds (nodules that protrude from the sides of each rhizome) on each section.

Fill 3-inch pots halfway with a good potting soil and then lay the rhizome sections flat on the soil. Then cover with more potting soil.

Water well and slip the pots into clear plastic bags to create a warmer temperature inside.

These pots need to be placed in the warmest place you can find (germination is most successful at temperatures between 25–30°C ). Sprouting at lower temperatures will be very slow. Rhizomes are also susceptible to rot during this period if the temperature is not sufficient.

Check on them every few days and once the sprouts start to emerge, pots should be moved to a windowsill or under a grow light. Optimal growing temperature at this stage is between 24–27°C . If the room doesn’t meet this temperature range, they should be placed on a heat mat.

Regularly check the soil inside the mini greenhouses to keep the soil moist, but not soggy. Misting the leaves once or twice a day with water to keep the humidity up is advised. Allowing the soil to dry out at any point will reduce your final harvest.

When plants reach around 6–8 inches tall they can be carefully transplanted into larger pots (either the final ones or an intermediate size) topping up the potting soil. Begin turning the heat mat down several degrees each week gradually down to around 21°C. At this point, you can remove the heat mat as long as your indoor temperature averages at around 20°C.

The plants can be taken outside when warmer nights are expected and all chance of frost has passed. Water as needed during the summer and autumn to keep the soil moist (but not soggy) (30).

-

Recipe

Natural balance tea

When digestive fire is low and metabolism feels sluggish, it cannot transform food into nourishing energy. Instead, food can get stored as fat, starting a vicious cycle where digestion becomes weaker and weaker, leading to steady weight gain. This delicious tea helps to stimulate the metabolism and supports your body to find a natural and balanced weight.

Ingredients

- Cinnamon bark 4 g

- Ginger root powder 2 g

- Orange peel 2 g

- Green tea 2 g

- Turmeric root powder 1 g

- Black pepper 1 g

- Orange essential oil a drop per cup

This will serve 2–3 cups of digestion enhancing, weight-balancing tea that works together with lots of exercise.

Method

- Put all of the ingredients in a pot (except for the orange essential oil).

- Add 500 ml (18fl oz) freshly boiled filtered water. Leave to steep for 10–15 minutes, then strain.

- Add one drop of orange essential oil to each cup

Let me glow tea

This delicious recipe is a healing blend of chlorophyll-rich herbs that purify the blood, soothe the liver and cleanse the skin, helping you glow from the inside out. Good for anyone with pimples, acne or other skin blemishes.

Ingredients

- Nettle leaf 3 g

- Fennel seed 2 g

- Peppermint leaf 2 g

- Dandelion root 2 g

- Burdock root 2 g

- Red clover 2 g

- Turmeric root powder 1 g

- Licorice root 1 g

- Lemon juice a twist per cup

This will serve 2 cups of beautifying tea.

Method

- Put all of the ingredients in a pot (except the lemon). Add 500 ml (18fl oz) freshly boiled filtered water.

- Leave to steep for 10–15 minutes, then strain and add the lemon.

Joint protector tea

It’s almost an inevitable human condition that we will suffer from some sort of joint pain as we get older. All that wear-and-tear throughout life can catch up with us but we have a herbal tea recipe that will help keep the red-hot inflammation of arthritis and gout at bay.

Ingredients

- Turmeric root powder 3 g

- Boswellia resin 2 g

- Ginger root powder 2 g

- Celery seed 2 g

- Ashwagandha root 1 g

- Liquorice root 1 g

- Meadowsweet leaf 1 g

- Honey to taste

This will serve 2–3 cups of ache-free tea.

Method

- Put all of the ingredients (except for the meadowsweet leaf and honey) in a saucepan with 600 ml (21fl oz) cold filtered water. Cover with a lid and simmer for 15 minutes.

- Take off the heat and add the meadowsweet leaf.

- Leave to steep for 10 minutes, strain and add some honey to taste.

Recipes from Cleanse, Nurture, Restore by Sebastian Pole

-

References

- Burge K, Gunasekaran A, Eckert J, Chaaban H. Curcumin and Intestinal Inflammatory Diseases: Molecular Mechanisms of Protection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019;20(8):1912. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20081912

- Ghiamati Yazdi F, Soleimanian-Zad S, van den Worm E, Folkerts G. Turmeric Extract: Potential Use as a Prebiotic and Anti-Inflammatory Compound? Plant Foods for Human Nutrition. 2019;74(3):293-299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11130-019-00733-x

- Jafarzadeh E, Shoeibi S, Bahramvand Y, et al. Turmeric for Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review of Population-Based Evidence. Iranian Journal of Public Health. 2022;51(6). https://doi.org/10.18502/ijph.v51i6.9656

- Verma R, Kumari P, Maurya R, Kumar V, Verma RB, Singh R. Medicinal properties of turmeric (Curcuma longa L.): A review. International Journal of Chemical Studies. 2018;6 (4):1354-1357.

- Mcintyre A. Complete Herbal Tutor : The Definitive Guide to the Principles and Practices of Herbal Medicine (Second Edition). Aeon Books Limited; 2019.

- Prasad S, Aggarwal BB. Turmeric, the Golden Spice. Nih.gov. Published 2011. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK92752/

- Jain D, Singh K, Gupta P, et al. Exploring Synergistic Benefits and Clinical Efficacy of Turmeric in Management of Inflammatory and Chronic Diseases: A Traditional Chinese Medicine Based Review. Pharmacological Research – Modern Chinese Medicine. Published online January 1, 2025:100572-100572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prmcm.2025.100572

- Dei Cas M, Ghidoni R. Dietary Curcumin: Correlation between Bioavailability and Health Potential. Nutrients. 2019;11(9):2147. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092147

- Tapal A, Tiku PK. Complexation of curcumin with soy protein isolate and its implications on solubility and stability of curcumin. Food Chemistry. 2012;130(4):960-965. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.08.025

- Ghosh S, Gehr T, Ghosh S. Curcumin and Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD): Major Mode of Action through Stimulating Endogenous Intestinal Alkaline Phosphatase. Molecules. 2014;19(12):20139-20156. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules191220139

- Patcharatrakul T, Gonlachanvit S. Chili Peppers, Curcumins, and Prebiotics in Gastrointestinal Health and Disease. Current Gastroenterology Reports. 2016;18(4):19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11894-016-0494-0

- Wang J, Ghosh SS, Ghosh S. Curcumin improves intestinal barrier function: modulation of intracellular signaling, and organization of tight junctions. American Journal of Physiology – Cell Physiology. 2017;312(4):C438-C445. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpcell.00235.2016

- Ghosh SS, He H, Wang J, Gehr TW, Ghosh S. Curcumin-mediated regulation of intestinal barrier function: The mechanism underlying its beneficial effects. Tissue Barriers. 2018;6(1):e1425085. https://doi.org/10.1080/21688370.2018.1425085

- Sreedhar R, Arumugam S, Thandavarayan RA, Karuppagounder V, Watanabe K. Curcumin as a therapeutic agent in the chemoprevention of inflammatory bowel disease. Drug Discovery Today. 2016;21(5):843-849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2016.03.007

- Schneider A, Hossain I, VanderMolen J, Nicol K. Comparison of remicade to curcumin for the treatment of Crohn’s disease: A systematic review. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2017;33:32-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2017.06.002

- Rasyid A, Rahman ARA, Jaalam K, Lelo A. Effect of different curcumin dosages on human gall bladder. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2002;11(4):314-318. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-6047.2002.00296.x

- Aggarwal BB, Yuan W, Li S, Gupta SC. Curcumin-free turmeric exhibits anti-inflammatory and anticancer activities: Identification of novel components of turmeric. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 2013;57(9):1529-1542. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201200838

- Orellana-Paucar A, Afrikanova T, Thomas J, et al. Insights from Zebrafish and Mouse Models on the Activity and Safety of Ar-Turmerone as a Potential Drug Candidate for the Treatment of Epilepsy. PLOS ONE. 2013;8(12):e81634-e81634. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0081634

- Park SY, Jin ML, Kim YH, Kim Y, Lee SJ. Anti-inflammatory effects of aromatic-turmerone through blocking of NF-κB, JNK, and p38 MAPK signaling pathways in amyloid β-stimulated microglia. International Immunopharmacology. 2012;14(1):13-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2012.06.003

- Yue GGL, Kwok HF, Lee JKM, et al. Novel anti-angiogenic effects of aromatic-turmerone, essential oil isolated from spice turmeric. Journal of Functional Foods. 2015;15:243-253. Accessed April 4, 2025. https://doaj.org/article/6c1cfdb6104546ab831a97eed7fa5f8b

- Hucklenbroich J, Klein R, Neumaier B, et al. Aromatic-turmerone induces neural stem cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo. Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2014;5(4):100. https://doi.org/10.1186/scrt500

- Park SY, Kim YH, Kim Y, Lee SJ. Aromatic-turmerone’s anti-inflammatory effects in microglial cells are mediated by protein kinase A and heme oxygenase-1 signaling. Neurochemistry International. 2012;61(5):767-777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2012.06.020

- Curcuma longa interactions. Natural Medicines. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/Tools/InteractionChecker. Accessed July 15, 2025.

- Thomsen M. Phytotherapy Desk Reference. 6th ed. Aeon Books; 2022.

- Chanda S, Ramachandra T. Phytochemical and Pharmacological Importance of Turmeric (Curcuma Longa): A Review.; 2019:16-23. https://wgbis.ces.iisc.ac.in/energy/water/paper/Turmeric/Pub_%20Phytochemical%20and%20Pharmacological%20Importance%20of%20Turmeric%20(1).pdf

- Cavaleri F. Presenting a New Standard Drug Model for Turmeric and Its Prized Extract, Curcumin. International Journal of Inflammation. 2018;2018:1-18. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/5023429

- Royal Botanical Gardens Kew. Turmeric | Kew. www.kew.org. Published 2025. https://www.kew.org/plants/turmeric

- Oleander S. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Curcuma longa. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Published May 31, 2019. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/88308047/88308057

- Team E. Sustainability in Turmeric Farming Reducing Environmental Impact and Enhancing Soil Health. EssFeed. Published March 17, 2025. Accessed April 7, 2025. https://essfeed.com/sustainability-in-turmeric-farming-reducing-environmental-impact-and-enhancing-soil-health-sustainability-in-turmeric-farming-reducing-environmental-impact-and-enhancing-soil-health/

- Global Health: The Spice Sellers Secret. Stanford Medicine Magazine. June 2023. https://stanmed.stanford.edu/turmeric-lead-risk-detect/. Accessed 21 December 2023.

- Marshall R. Grow Your Own Turmeric – by Roger Marshall. Hartley Botanic. Published November 24, 2021. Accessed April 7, 2025. https://hartley-botanic.co.uk/magazine/grow-your-own-turmeric/