-

How does it feel?

The plant itself has a delicate and soft sensation to the touch. When rubbed, all aerial parts, but particularly the leaves release a strong scent, which has been described as unpleasant. The flowers have a nutty flavour and are slightly astringent.

-

What can I use it for?

With its high tannin content, herb robert is particularly indicated where astringency is required. It is used for the gastrointestinal system, for peptic ulcers, gastric ulcers or diarrhoea. In the reproductive system, it can be used for metrorrhagia and menorrhagia (1). A hot water infusion, once cooled, can be used as a mouthwash for gum disease or sore throats as well as for skin conditions, where astringency is called for (2).

Bruton-Seal & Seal (2017) suggest that it may be used similarly to the much more well known American species Geranium maculatum, and, traditionally, various geranium species were used interchangeably in the past (2). As a vulnerary and anti-inflammatory, it may help with wound healing, burns and cold sores (3).

-

Into the heart of herb robert

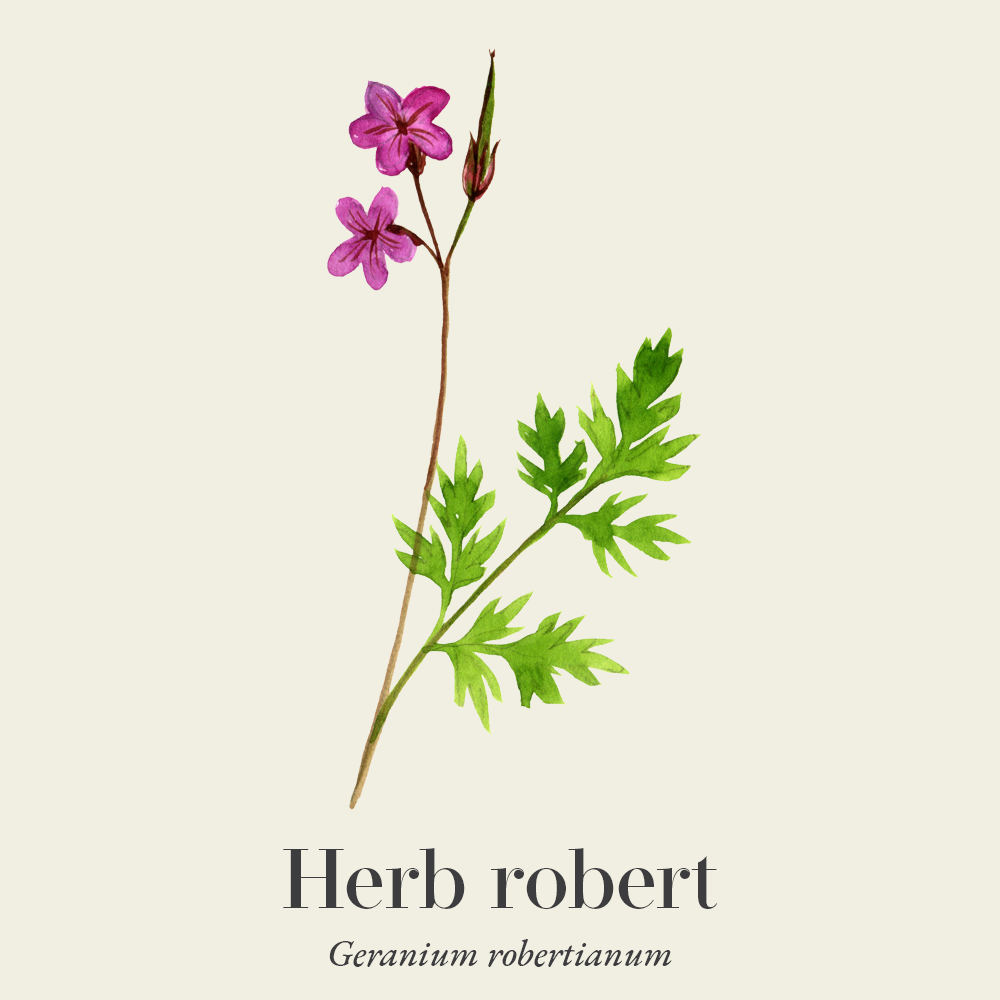

Herb robert (Geranium robertianum) In modern times, this herb is often neglected in common Materia Medica. This is perhaps a reflection of its deceptively delicate nature, with its small appearance, slender stalks and delicate leaves and flowers. However, its widespread habitat all over the world, as well as its ability to grow in the tiniest cracks and rocky places, full sun as well as shade, suggests a great adaptability and strength. Its stems are off a dark red colour, lending itself to the signature for the treatment of conditions involving blood.

Perhaps somewhat surprising to those unfamiliar with herb robert, is its strong pungent smell, which suggests the presence of volatile oils and is part of its defence mechanism (alongside the bitter molecule geraniin, and the high tannin content) against predators and can be used to repel midges and other biting insects by rubbing the fresh plant on the skin (2). These essential oils have been found to have antimicrobial properties, especially against gram-positive bacteria, perhaps contributing to the overall vulnerary effects of the plant (4).

-

Traditional uses

The most common association is its use in healing wounds and ulcers and to stop bleeding. The herb seems to be known for these qualities in various parts of the world. However, in Italy the herb was also traditionally used for the urinary system and for infertility (5). And in Portuguese herbal medicine, the herb is known for its hypoglycaemic properties (6). Barker reports that the herb has a folk tradition for being used for cancer, but while there exists some evidence, it is not enough and thus “one is ill-advised either to dismiss or to promote it” (1). Modern research indeed shows that the herb has some cytostatic and antioxidant properties that may make it a useful chemotherapeutic agent, though further research is needed (7).

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

Western energetics

Ayurvedic energetics

-

What practitioners say

Skin

Skin Herb robert can be thought of as an effective first aid herb, by helping to stop nosebleeds, acting as a styptic for wounds or soothing burns (8). The tannins contribute to this through their astringent and haemostatic properties. Geraniin, a type of ellagitannin, has been found to have high antioxidant and antimicrobial properties (9,10).The flavonoids, phenolic acids and essential oils also contribute to these actions with their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and mildly antimicrobial properties. Herb robert may also be useful for skin conditions of a more chronic nature such as varicose veins. Additionally, when rubbed on the skin it may help to repel insects.

Gastrointestinal system

As with its topical wound healing properties, herb robert’s anti-inflammatory, astringent and antimicrobial effects are of benefit to the treatment of ulceration, inflammation or problems associated with diarrhoea in the gastrointestinal tract, and may explain its longstanding traditional use for these types of conditions (10).

Endocrine system

Herb robert may be considered within the treatment of type 2 diabetes due to its effect on lowering blood glucose levels and supporting mitochondrial function (3).

-

Research

Herb robert (Geranium robertianum) “MitoTea”: Geranium robertianum L. decoctions decrease blood glucose levels and improve liver mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in diabetic Goto–Kakizaki rats

In this 2010 study, researchers evaluated the effects of Geranium robertianum leaf decoctions on glucose metabolism and mitochondrial function in Goto–Kakizaki rats, a non‐obese model of type 2 diabetes. Over a four‑week period, diabetic rats received daily oral doses of the decoction. Compared to untreated controls, treated rats exhibited significantly reduced fasting plasma glucose levels, demonstrating a clear hypoglycemic effect.

Furthermore, liver mitochondria were isolated to assess respiratory performance. The decoction enhanced mitochondrial respiration, indicating overall improvement in electron transport chain efficiency. Notably, the oxidative phosphorylation efficiency — a key measure of how effectively mitochondria convert nutrients into ATP — was also significantly elevated.

These findings suggest that the bioactive compounds in herb robert not only lowers blood glucose but also restores mitochondrial energy metabolism in diabetic conditions. Such dual effects — enhancing glycemic control while improving hepatic mitochondrial function — point to its potential as a complementary therapeutic agent for type 2 diabetes (6).

Promising effect of Geranium robertianum L. leaves and aloe vera gel powder on Aspirin®-induced gastric ulcers in Wistar rats: anxiolytic behavioural effect, antioxidant activity, and protective pathways

This in-vivo study assessed Geranium robertianum leaf decoction and aloe vera gel powder for their protective effects against aspirin-induced gastric ulcers in female Wistar rats. Forty rats were split into five groups: a negative control, a positive ulcer control, and three pretreated groups receiving aloe, geranium, or the reference drug famotidine.

Phytochemical analysis revealed that both treatments were rich in polyphenols and exhibited strong antioxidant activity, including free-radical scavenging and ferric-reducing power. Pretreated rats showed significant improvements in locomotor function and anxiety-like behaviors compared to ulcer-only animals. Ultrasonography and histopathology confirmed reduced gastric wall thickening and mucosal damage.

Biochemically, both extracts lowered ulcer index (geranium achieved ~88.5% protection; aloe ~84.2%), decreased gastric juice volume while raising pH, reduced oxidative stress, and downregulated pro‑inflammatory markers.

The researchers concluded that Geranium robertianum and aloe vera offer potent gastroprotective effects in aspirin-induced ulcers via antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anxiolytic, and mucosal-preserving mechanisms, highlighting their therapeutic potential for gastric ulcer prevention or treatment (11).

Herb robert’s Gift against human diseases: Anticancer and antimicrobial activity of Geranium robertianum L.

The study analysed four extracts (hexane, ethyl acetate, methanol, aqueous) from commercially sourced, certified organic herb robert aerial parts. The researchers identified a diverse phytochemical profile including organic and phenolic acids, gallo- and ellagitannins, and flavonoids. Subsequent bioassays revealed that both hexane (GrH) and ethyl acetate (GrEA) extracts showed notable anticancer activity, with selectivity indices ranging from 2.0 to 4.4, indicating preferential toxicity toward cancer cells.

Antiviral assays demonstrated that both hexane and ethyl acetate effectively inhibited HHV‑1 cytopathic effects and viral load, reducing viral replication by 0.5 log (GrH) and 1.4 log (GrEA). Notably, active fractions from GrEA further decreased viral activity.

Furthermore, the extracts and their fractions exhibited broad antibacterial and antifungal effects, particularly against gram‑positive bacteria. A standout fraction, GrEA4, inhibited Micrococcus luteus (MIC = 8 µg/mL), S. epidermidis (16 µg/mL), S. aureus, E. faecalis, and B. subtilis (MICs = 125 µg/mL), supporting its traditional use in treating persistent wounds.

The research concludes that G. robertianum extracts — especially ethyl acetate and hexane fractions — demonstrate promising anticancer, antiviral, and antibacterial activity. Their selectivity toward cancer cells and efficacy across pathogens underscore the plant’s therapeutic potential against human diseases (12).

-

Did you know?

Herb robert and the other members of the crane’s-bill family, Geraniaceae, are so called because of the unique structure of their seed pods, which resemble a crane’s bill. This family contains more than 800 species worldwide. Two of the largest subgroups, the Geranium genus (the cranesbills) and the Erodium genus (the storksbills), have pink, red, mauve or blue five-petalled flowers. When mature, the seed pods dry and spring open, ejecting seeds, along with a spring-like structure, with force, allowing them to travel up six meters. This method of dispersal helps members of this family, including herb robert, spread rapidly and colonise new areas (13).

Additional information

-

Botanical description

Herb robert is a small plant, usually growing to around 30 cm in height. The soft triangle-shaped leaves are compound, formed by multiple leaflets with lobed or serrated margins adhered to a single petiole (3). Leaves and stalks tend to be covered in tiny hairs, giving the plant a soft feel. Stalks and leaves may be entirely green, but can turn a deep red, especially if the plants are growing in bright sunshine and dry conditions. The flowers have a delicate pink colour and the herb can be found flowering from early spring through to late autumn in the UK. Once pollinated, the typical storkbill shaped fruit pods form, which once matured eject the seeds into the surrounding environment. Plants tend to be biennial.

-

Common names

- Herb Robert

- Stinking Bob

- Red Robin

- Death-come-quickly

- Crow’s Foot

- Storksbill

- Squinter-pip

-

Safety

Since this is not a commonly used medicinal herb, not much is known about any safety considerations. Safety of this herb has not been established for use during pregnancy or lactation (14).

-

Interactions

None known (14)

-

Contraindications

None known (14)

-

Preparations

- Infusion

- Tincture

-

Dosage

- Tincture (ratio 1:5| 25%): 0.5–5ml, up to three times daily (1)

- Infusion/decoction: 25 g to 500 ml. Double strength for topical use (1).

-

Plant parts used

- Leaves

- Flowering tops

-

Constituents

- Tannins: Hydrolisable tannins, more specifically ellagitannins- the main one in G. robertianum being Geraniin, which exhibits potent antioxidant activity (15)

- Condensed tannins: Proanthocyanidins (16)

- Phenolic acids: Egallic acid, gallic acid, ferulic acid, caffeic acid, caftaric acid (16)

- Flavonoids: Quercetin, kaempferol, rutin, quercetin, hyperoside (16)

- Vitamins: C, A, B1, B3 and vitamin E (16)

- Minerals: Calcium, sodium and iron (16)

- Essential oils: Over a 100 different compounds have been detected, the main ones being linalool, 𝛾-terpinene, germacrene-D, limonene, geraniol, α-terpineol and phytol (16).

-

Habitat

The native range of Geranium robertianum spans much of Europe, parts of North Africa, western Asia. and eastern parts of North America. It has been introduced and naturalised in New Zealand, and other temperate regions (17). It typically grows in shaded or semi-shaded environments, including woodlands, hedgerows, rocky crevices, and along the edges of paths and walls and has a wide ecological amplitude — ranging from Mediterranean to boreal and across oceanic to continental conditions (18).

-

Sustainability

Not currently on risk lists but complete data may be missing on the status of the species. Read more in our sustainability guide. Given its wide distribution around the world, Geranium robertianum is currently under no threat of extinction (17,19). The IUCN has not assessed the threat status of this species (20).The herb is also not currently available on a commercial scale and grows wild in many places in the UK and, therefore, there is little threat from overharvesting.

Habitat loss and over-harvesting from the wild are two of the biggest threats faced by medicinal plant species. There are an increasing number of well-known herbal medicines at risk of extinction. We must, therefore, ensure that we source our medicines with sustainability in mind.

The herb supplement industry is growing at a rapid rate and until recent years a vast majority of medicinal plant produce in global trade was of unknown origin. There are some very real and urgent issues surrounding sustainability in the herb industry. These include environmental factors that affect the medicinal viability of herbs, the safety of the habitats that they are taken from, as well as the welfare of workers in the trade.

The botanical supply chain efforts for improved visibility (transparency and traceability) into verifiably sustainable production sites around the world is now certificated through the emergence of credible international voluntary sustainability standards (VSS).

Read our article on Herbal quality & safety: What to know before you buy and Sustainable sourcing of herbs to learn more about what to look for and questions to ask suppliers about sustainability.

-

Quality control

Herbal medicines are often very safe to take; however, their safety and efficacy can be jeopardised by quality issues. So, it is important to buy herbal medicines from a reputable supplier, from sources known to test their herbs to ensure there is no contamination, adulteration or substitution with incorrect plant matter, as well as ensuring that recognised marker compounds are at appropriate levels in the herbs.

Some important quality assurances to look for are certified organic labelling, the correct scientific/botanical name, and the availability of information from the supplier about ingredient origins. A supplier should be able to tell you where the herbs have come from, what contaminants are not in the herb, and what the primary compounds are.

-

How to grow

Herb robert grows easily in most habitats within the temperate climate and is mostly regarded as a weed that needs to be weeded out. Given its effective seed dispersal mechanism, it will easily spread once on site. For bigger, more leafy plants, grow in rich soil and semishade; however, it will tolerate most soil types and conditions. It is a hardy annual or biennial plant (21).

-

Recipe

Herb robert mouthwash (Geranium robertianum) Herb robert mouthwash

This mouthwash will help to reduce inflammation and soothe inflamed or irritated gums. Its antibacterial action helps to reduce dental plaque and gum infections.

Ingredients

- Two teaspoons dried herb robert

- Two cloves

- 250 ml boiled filtered water

How to make herb robert mouthwash

- Boil the kettle with the filtered water.

- Pour onto the herbs and leave to steep for 10 minutes.

- Strain and let the mixture cool.

- Use two tablespoons of the liquid to rinse and swill in the mouth for one minute and spit out afterwards. Do not swallow.

- Repeat daily for maximum effects.

-

References

- Barker J. The Medicinal Flora of Britain & Northwest Europe : A Field Guide, Including Plants Commonly Cultivated in the Region. Winter Press; 2001.

- Bruton-Seal J. Wayside Medicine : Forgotten Plants to Make Your Own Herbal Remedies. Merlin Unwin Books; 2017.

- Ali DH, Dărăban AM, Ungureanu D, et al. An Up-to-Date Review Regarding the Biological Activity of Geranium robertianum L. Plants. 2025;14(6):918-918. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14060918

- Elzbieta Gebarowska, Politowicz J, Antoni Szumny. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of geranium robertianum L. essential oil. PubMed. 2017;74(2):699-705.

- Petelka J, Plagg B, Säumel I, Zerbe S. Traditional medicinal plants in South Tyrol (northern Italy, southern Alps): biodiversity and use. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2020;16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-020-00419-8

- Ferreira FM, Peixoto F, Nunes E, Sena C, Seiça R, Santos MS. “MitoTea”: Geranium robertianum L. decoctions decrease blood glucose levels and improve liver mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats. Acta biochimica Polonica. 2010;57(4):399-402. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21046015/

- Neagu E, Paun G, Constantin D, Radu GL. Cytostatic activity of Geranium robertianum L. extracts processed by membrane procedures. Arabian Journal of Chemistry. 2017;10:S2547-S2553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2013.09.028

- Alshehri B. The geranium genus: A comprehensive study on ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemical compounds, and pharmacological importance. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 2024;31(4):103940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2024.103940

- Wang P, Peng X, Wei ZF, et al. Geraniin exerts cytoprotective effect against cellular oxidative stress by upregulation of Nrf2-mediated antioxidant enzyme expression via PI3K/AKT and ERK1/2 pathway. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – General Subjects. 2015;1850(9):1751-1761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2015.04.010

- Boakye Y, Agyare C. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of geraniin and aqueous leaf extract of Phyllanthus muellerianus (Kuntze) Exell. Planta Medica. 2013;79(13). https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1352024

- Abd M, Rabab MA, Gohari ST, et al. Promising effect of Geranium robertianum L. leaves and Aloe vera gel powder on Aspirin®-induced gastric ulcers in Wistar rats: anxiolytic behavioural effect, antioxidant activity, and protective pathways. Inflammopharmacology. Published online May 15, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-023-01205-0

- Świątek Ł, Wasilewska I, Boguszewska A, et al. Herb Robert’s Gift against Human Diseases: Anticancer and Antimicrobial Activity of Geranium robertianum L. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(5):1561. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15051561

- Lis-Balchin L. Geranium and Pelargonium: History of Nomenclature, Usage and Cultivation. Informa; 2002. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780203216538

- Natural Medicines Database. Herb Robert. Therapeuticresearch.com. Published 2025. Accessed August 4, 2025. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/Data/ProMonographs/Herb-Robert

- Perera A, Ton SH, Palanisamy UD. Perspectives on geraniin, a multifunctional natural bioactive compound. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2015;44(2):243-257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2015.04.010

- Graça VC, Ferreira ICFR, Santos PF. Phytochemical composition and biological activities of Geranium robertianum L.: A review. Industrial Crops and Products. 2016;87:363-378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.04.058

- Royal Botanical Gardens Kew. Geranium robertianum L. | Plants of the World Online | Kew Science. Plants of the World Online. Published 2017. Accessed August 4, 2025. https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:109269-2

- TOFTS RJ. Geranium robertianum L. Journal of Ecology. 2004;92(3):537-555. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-0477.2004.00892.x

- BSBI Plant Atlas 2020. PlantAtlas. Plantatlas2020.org. Published 2019. https://plantatlas2020.org/atlas/2cd4p9h.8nb

- IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN Red List. Published 2025. https://www.iucnredlist.org/

- RHS. Herb robert / RHS Gardening. www.rhs.org.uk. Published 2025. https://www.rhs.org.uk/weeds/herb-robert