Whilst Ayurveda and TCM retained a constitutional approach to medicine, it was lost in Western practice. Stephen Taylor introduces humoral medicine, an ancient medical system based on the elements.

Humoral medicine is the traditional ancient health care system of the Western world. It is intrinsically holistic in its viewpoint taking its starting point from the belief that the nature of the cosmos is a harmonious interaction of all its parts.

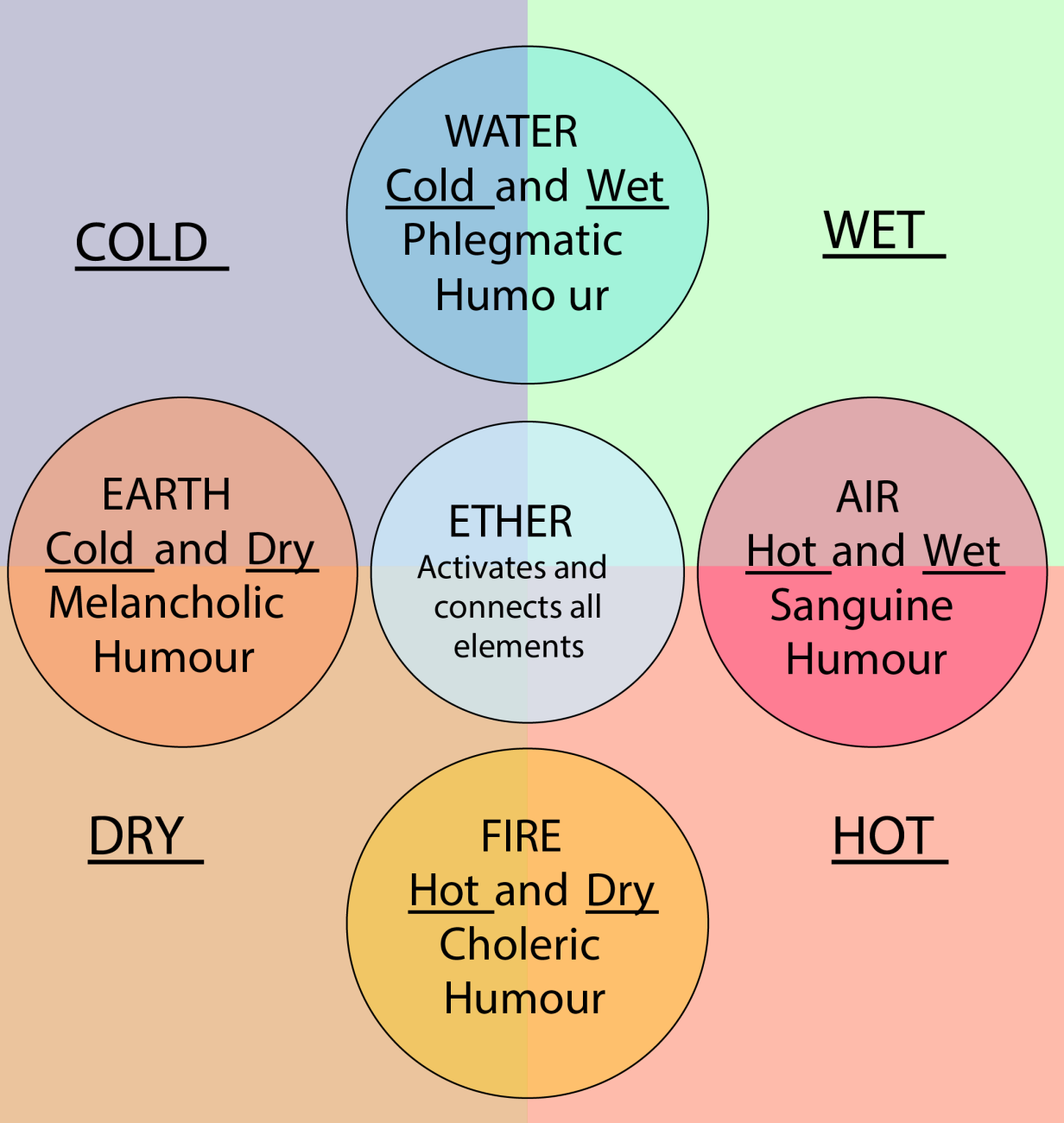

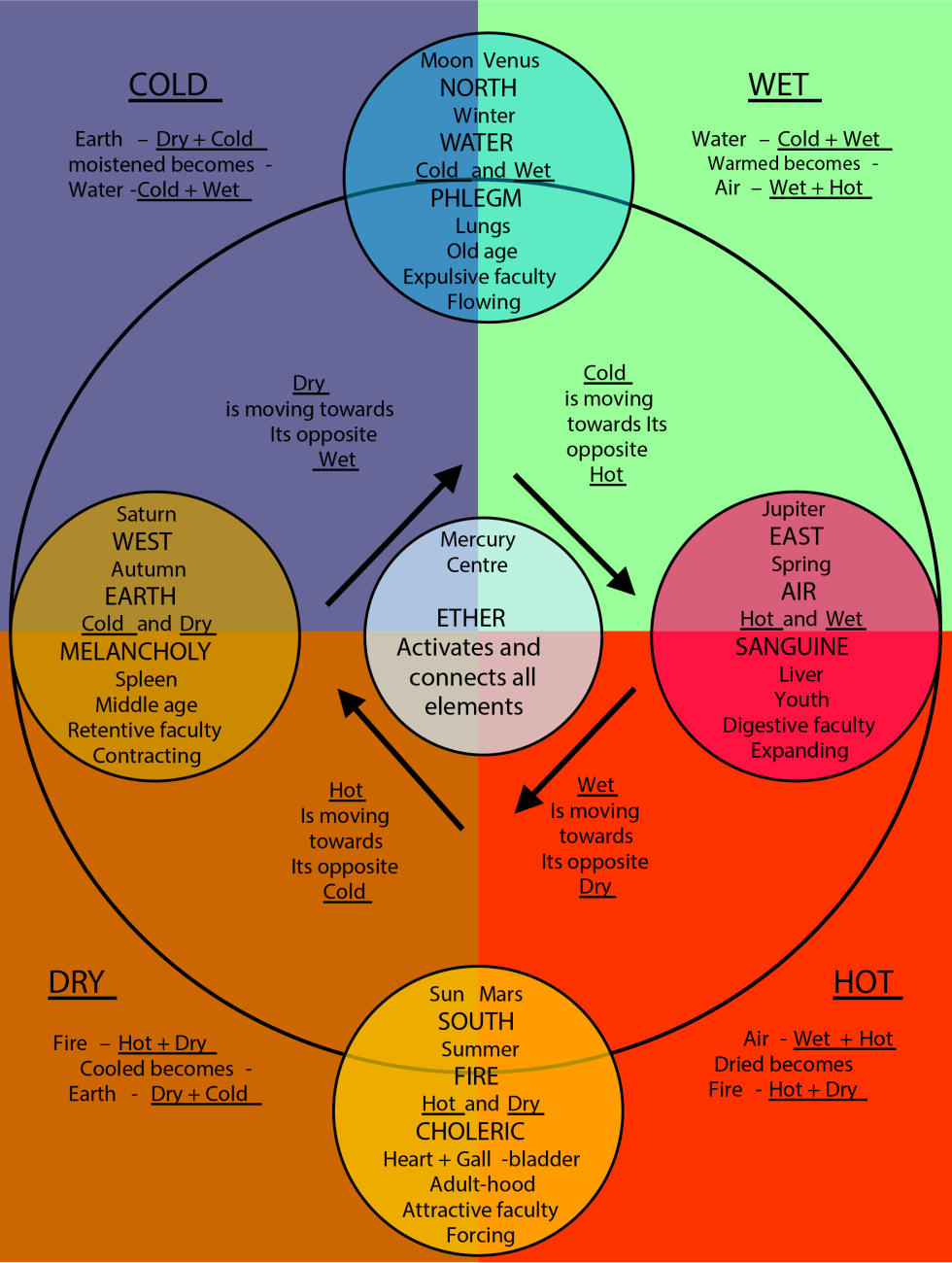

Humoral medicine evolved out of a world view shared across the Eurasian continent that described all natural phenomena as being combinations of basic elements. These elements are identified by a combination of the ‘qualities’ hot and cold, wet and dry.

Humoral philosophy was formalised in Western culture around 400 BCE within the ‘Hippocratic School’ of medicine. This was the medical practice of the Ancient Greek world and was used within healing temple complexes called Asclepions, it was further refined by the Roman physician Galen in the second century ACE.

In the early medieval period humoral medical philosophy was revived in Europe via the arrival of Arabic translations of the original Hippocratic and Galenic texts. By the Sixteenth century the humoral system had been further enriched by the addition of the mystical philosophy of Hermeticism, a tradition contained in the ‘Corpus Hermeticum’ written around 300 BCE. Hermeticism envisioned existence to be created from a divine source, which through the medium of ether vitalised and connected all living things.

The basic elements in humoral philosophy are air, fire, earth, water and ether. Ether is akin to space and emptiness, it is thought of as a medium which has no substance or qualities of its own but accommodates and enables the interaction of the four physical elements. It is within ether that the life force or ‘pneuma’ is transmitted and absorbed into the body via the breath.

When these elements manifest in either physical or non-physical ways in the body they are referred to as ‘humours’.

The temperamental qualities of the humours engender and impart a particular ‘temperament’ or heat wherever they manifest, and every aspect of the living body has an ideal temperament or humour within which it functions best.

This means that organs, systems and people have a particular correspondence to a humour depending on their ideal or natural temperament. For instance, the lungs, stomach, kidneys, bladder, bowels and brain are all said to have a generally moist and cool temperament, and are therefore considered to be phlegmatic organs connected to the water element. Whilst the gall bladder, full of acidic or ‘hot’ bile is said to be a choleric organ, with an association to the fire element.

The health of any organ, system, tissue, or bodily function is best maintained when it is held in its correct or ideal temperament. The role of medicine is to promote the ideal temperament of the various bodily organs and functions and restore them when they have lost their correct balance or ratio of humours.

When the balance of a temperament is lost, herbs, diet and lifestyle may be used to return the organ, system or person back to the most beneficial temperamental state. This is done through both countering the change with its opposite, for instance using heating remedies when coldness overwhelms etc., or by strengthening the correct temperament through supporting its natural processes of homeostasis. These are called the antipathetic (countering), and the sympathetic (supporting) approaches.

Humoral medicine proposes that the excess of one or more of the humours is the main cause of loss of natural balance, and although this will initially present in the form of excess it often leads to a depletion of vitality. This means that when we see a lack of natural vitality, we must primarily determine what humour has been in excess and has overwhelmed the system causing imbalance.

The humours

Most of us are already likely to be familiar with the qualities and names of these four Humours:

- Air: Sanguine or blood humour — hot and wet

- Fire: Choleric humour — hot and dry

- Earth: Melancholic humour — cold and dry

- Water: Phlegmatic humour — cold and wet

Perhaps the first guiding concept of humoral theory that we have not retained in the Western biomedical model is the role of cycles in health and disease.

In all ancient medical systems and traditions, rhythm and cycles are understood as the core expression of life, and the loss of cycle is associated with sickness and ill health.

We frequently find the ancient concept of dynamic cosmic change and repetitive cycles expressed through the symbol of a circle; it has no beginning, no end, it is in continual motion. It also corresponds to the world around us; the circular and cyclical nature of the sun and moon, the circle and cycle of the continual dance of day and night, the cycle of the four seasons coming, going and returning, the circle and cycle of being born from the earth and returning to the earth at death.

The humours themselves are bodily manifestations of the phases of movement in this cycle, a movement we see reflected in the seasonal cycle; winter — cold and wet, through spring — hot and wet, to summer — hot and dry, and back again through autumn — cold and dry. This humoral cycle is seen in the life cycle with spring being birth and youth, summer adulthood, autumn middle age, and winter old age and death.

The activity of the humours in the body is likened to the seasonal changes that make up the annual cycle of growth and regeneration in the world around us. If the seasonal temperaments are in balance and there is a year without extreme heat and drought, or without extreme cold and wet flooding the land; everything grows well, and there will be a plentiful harvest.

Similarly, if the humours are well balanced like good seasons, the vitality of the body is nourished. This living vitality then manifests in the body as healthy and strong ‘spirits’. Loss of health arises when one aspect of the cycle becomes excessive and overwhelms the body.

A fever may be likened to a heat wave in the summer, which although can be made easier by finding a cool breezy place offering instant respite, it will only properly resolve when the balancing coolness of autumn arrives.

When treating a fever, we must first address the excess temperature by using cooling strategies, such as swabbing with a tepid cloth and giving antipyretics, such as willow (Salix alba). But, we also need to find a way to move things on to the next cooler phase, for instance using sweat inducing and immune stimulating diaphoretics (traditional cleansing cathartic herbs) such as vervain (Verbena officinalis) or elder (Sambucus nigra). This is like moving the fever cycle from being stuck in summer heat into the cooler days of autumn.

It is then important to consider what excess humour initially overwhelmed the system and lead to the depletion of the vital spirit and its innate heat, as it is this heat that confers protection against any ‘invasion of poisons’ (infection and fevers).

When the underlying temperamental balance is lost, the most powerful way of bringing the balance back is through using sympathetic supportive strategies, even if we have to initially respond with countering ‘antipathetic’ interventions to address the immediate imbalance.

Sympathetic supportive strategies consist of:

- Restoring and nourishing weakened tissues and organs ensuring that their temperament is returned to normal.

- Supporting any weakened ‘spirits’, including the organs that they reside in — the heart, the head, the liver, the reproductive organs.

- Using constitutional medicines that help to balance the individual’s dominant humour, or effects of their stage of life.

The spirits

Even today when we ask someone if they are in ‘good spirits’, or if they are feeling ‘dispirited’ we are continuing the use of these ancient humoral concepts in our language.

In humoral physiology there are four spirits which arise in the body.

- The vital spirit resides in the heart and consists of the innate heat and radical moisture. It activates all the bodily functions, gives the body its vitality, and protects it from infection.

- The natural spirit resides in the liver, it enables digestion and the dispersal of the humours in healthy blood.

- The animal spirit resides in the head, corresponds to the element ether, and initiates motivation, movement, and sensory perception.

- The procreative spirit resides in the testes, ovaries and womb. It arises as desire and provides the ability to conceive and procreate.

Causes of loss of temperament

As the loss of correct temperament is the main underlying cause of sickness, we need to look at its main possible causes.

- Life stage

- Constitution

- External influences

Lifecycle

Each stage of life is dominated by a particular humour, during each phase it is more likely that a loss of temperament will be caused by the dominant humour of that stage becoming an overwhelming influence:

- Youth: Sanguine / air

- Adulthood: Choler / fire

- Middle age: Melancholic / earth

- Old age: Phlegm / water

Individual constitution

Each person is born with a constitutional temperament, and this remains the same throughout life. We can quickly recognise the dominant temperament of some people, in others it may be a bit more subtle. We automatically recognise ‘warm’ people and ‘hot’ fiery people, as well as those who are ‘cool and chilled’, or perhaps even ‘cold’.

Determining a person’s constitution is important, as the temperament that dominates is always most likely to be the underlying cause of an imbalance for any individual. Having this temperament as a dominant influence in our bodies makes it always most likely to be the one which will become excessive.

Sanguine / air constitution

We all know the energetic, explorative, creative, embracing but slightly flighty types, the ones who can’t stay still for too long, who being similar to an energetic youngster have an exuberant sanguine/air temperament.

Choleric / fire constitution

These are those with a strong personal drive, focus, high motivation, and often low tolerance of failure and a short temper, this typifies the time of our lives when we are working toward goals as adults and corresponds to the choleric/ fire temperament.

Melancholic / earth constitution

We expect these types to be more introverted, solitary and studious, also reliable and trustworthy, often going deeply into ideas, but often prone to getting a bit stuck. This corresponds to middle age, when we slow down, become steadier and more anchored in our lives. This more grounded energy is the melancholic/earth temperament.

Phlegmatic / water constitution

Like the water element that rules them, phlegmatics are more likely to accommodate and flow with others, being more tolerant, but also a bit dreamy, and prone to getting overwhelmed. This corresponds to becoming an elder, with the wisdom of age making one more tolerant, and being able to let go of fixed ideas and attitudes. This softer gentler energy corresponds to the phlegmatic/water temperament.

Each of these four temperaments may manifest in combination with another, one still being the dominant aspect and one being secondary.

External factors affecting the temperament

In humoral medicine, there is a recognition that external factors have a very important influence on health and disease. These are seen as influences that arise from outside of the body rather than from its own nature, thus they are named the ‘six non-naturals.’

Air

The natural temperament of air is cold and moist like the lungs. When hot it may irritate the naturally damp lungs and blood, and when too cold and moist it may add to excess moisture causing putrefaction and infection. Each constitution is balanced by air of the opposite temperament — cool air for hot people, etc. Purity of air is of utmost importance.

Diet

Foods all have an intrinsic heat or cold, and each of the different constitutions are challenged or benefitted by them. In summer, the digestive heat is more dispersed due to the summer heat, and in winter, digestive heat is concentrated in the body. This corresponds to us eating more lightly in the summer with a preponderance for cooling foods such as lettuce, chicory and cucumber. Hotter people have stronger digestive heat and better digestion than cool phlegmatics, who benefit from always adding warming herbs, spices and pepper to their food.

Exercise and rest

Exercise activates innate heat and energises the body. The heat of excess exercise damages the body, and lack of exercise leads to stagnation and congestion.

Sleep and wakefulness

Sleep is brought on by the rising upwards of a sweet calming restoring vapour from the heart to the head. It has a moistening and refreshing effect on the brain and the nerves. During sleep the innate heat settles in the liver completing digestion and the production of the humours. Insomnia dissipates the spirits and dries the brain.

Retention and evacuation

The body has a retentive faculty associated with the Earth element and the spleen, and an expulsive faculty associated with the Water element, the bowels and bladder. If either faculty is lowered through disease, an excess of the retentive melancholic humour, or inadequate innate heat or moisture to activate the expulsive faculty then blockage occurs. This kind of congestion can lead to melancholic vapours rising up from the spleen effecting the heart, stomach and head.

Perturbations of the mind and emotions

The maintenance of a calm state throughout the body and mind is beneficial to health. Reducing stress and releasing extreme emotions through cathartic activities is very helpful. Singing, dancing, and expressing emotions in a healthy way are all considered very important, especially to the health of the vital spirit. Activities that promote joyfulness and practicing kindness are as important as any other measure we may take to maintain health.

Summary

Although the physiological and anatomical descriptions that underpin the historic humoral model now seem to be redundant due to our advances in the understanding of human biology and physiology, we shouldn’t discount the many important insights it can offer which have been drawn from millennia of medical observation and practice. Through embracing the humoral system, we gain a therapeutic model with which we can anchor our herbal practice to a holistic core.