-

How does it feel?

-

What can I use it for?

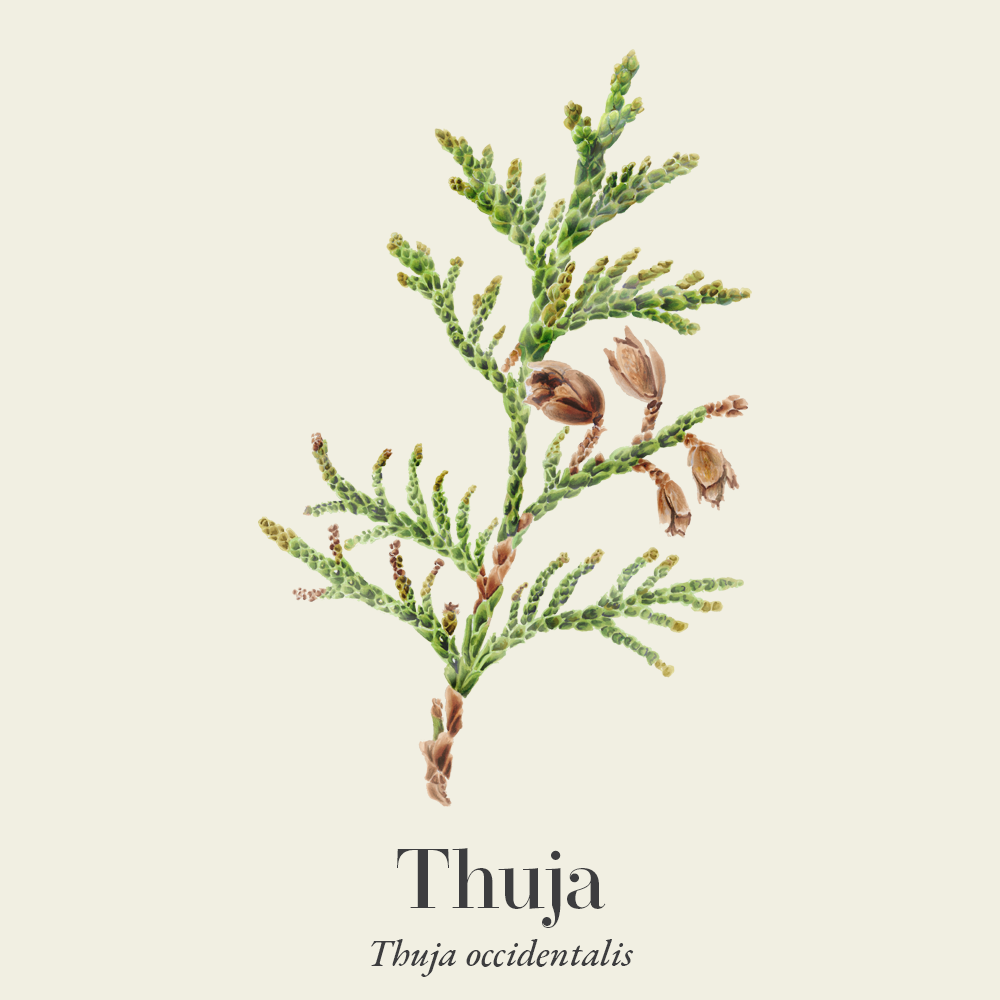

Thuja (Thuja occidentalis) Thuja may be used to treat viral infections affecting the skin, respiratory and other body systems. It has been shown to be active against herpes and other viruses including some strains of influenza. Internally, it may be given together with other herbs such as echinacea (Echinacea angustifolia) and wild indigo (Baptisia tinctoria) as a preventative medicine or to treat chronic viral conditions (1). Thuja can be prescribed for respiratory conditions, owing to its qualities as as a stimulating expectorant, diaphoretic and immune tonic.

The combined alterative, antimicrobial, antifungal and diuretic properties are helpful in treating a range of skin conditions including tinea, ringworm, eczema, and psoriasis. Thuja is commonly used topically, being applied repeatedly in tincture form onto warts and verrucas. It can be similarly applied to nasal polyps or taken internally to reduce fibroids and other growths (2). It is used for treating virally induced cancers, such as squamous cell in the mouth and throat, cervical cancer, melanoma, and lymphoma. Thuja can also be applied for pelvic and reproductive system cancers(3).

Thuja stimulates smooth muscle in the heart, bladder and uterus, improving muscle tone in the urinary system and treating incontinence where this is the cause. It can also stimulate uterine contractions in cases of amenorrhoea (4).

-

Into the heart of thuja

The thuja tree, when mature, gives a sense of strength and permanence. It has a strong presence, the wood is rot-resistant and the oil is powerful against pathogens. Although rarely so long-lived, some trees in North America have been found to be over 800 years old and a few well over 1,000 (5). The branches spread almost horizontally and are thickly layered so that the reddish trunk is almost hidden, giving a sense of its protective nature and strong defense.

A spicy insect repellent aroma comes from the leaves. Repeated handling of the foliage can irritate the skin, with a place in poison guides,due to the thujone content of the essential oil, thuja deserves respect and care in medicinal use (6).

It is thanks also to the power of the essential oil that thuja has become a familiar part of many herbal treatments and is featured in ongoing research. Looked upon as a systemic resolvent in cases of lymphatic stagnation, it is valued in skin and mucosal conditions alike (7).

-

Traditional uses

Thuja (Thuja occidentalis) In the 18th century in the Quebec area of its native Canada, thuja leaves were pounded in a mortar with grease and the mix boiled to make a salve which was spread on linen and applied to relieve rheumatic pain. The Iroquois people used thuja to treat coughs and the decoction was taken to relieve intermittent fevers near Saratoga (8).

The Eclectic physicians used thuja to treat multiple conditions. Ellingwood gives a long and enthusiastic entry peppered with examples of cases treated. He advises beginning with a small dose which might be raised as necessary. He presents thuja as a herb to be used, among other conditions, for gangrenous ulcers, treating blood dyscrasias and abnormal growths of the skin or mucous membranes (9). Thuja was listed in the US Pharmacopoeia from 1882–1894 as a uterine stimulant and diuretic (10).

Physio-medicalists in America widened the use treating several cancers, amenorrhoea and venereal warts with thuja preparations. They continued native American use as a counterirritant for rheumatism and pain and combined thuja and witch hazel (Hamamelis virginiana) to relieve eczema (11). In Britain it was included in the Extra Pharmacopoeia of 1885 and 1892 as being used to remove warts and fungoid granulations from ulcers. Internal use was for amenorrhoea, pulmonary catarrh, and worms (12). Early use to counteract the effects of the smallpox vaccination has been repeatedly referred to (13,14,15).

In summary, thuja has had a wide range of traditional uses in treating mucosal conditions including bronchial catarrh and intermittent fevers. Tincture from the bark as well as from the leaves has been applied to remove small warts, the treatment sometimes lasting several weeks (16). Additionally, urinary problems such as enuresis, cystitis, and urethritis, have all benefitted from thuja. Most frequent are references to treatments for skin conditions such as psoriasis. The herb or tincture has been applied topically for fungal skin infections, skin ulcers, and carcinomatous ulcerations. The stimulant effect on the uterus has meant thuja has been prescribed to treat amenorrhea (2). Thuja was also used to treat uterine cancer by Eclectic physicians(13).

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

Western energetics

-

What practitioners say

Cardiovascular system

Cardiovascular systemSeveral authors comment on the stimulating action of thuja for the heart muscle and it appears in the British Herbal Pharmacopoeia as specifically indicated in bronchitis with cardiac weakness, for this reason (14).

Immune system

Thuja offers support to the immune system against pathogens due to its antiviral, antibacterial and antifungal roles (15). It is seen as a key herb for treating chronic viral infections (1). Thuja and echinacea may be the most important herbs for adjuvant treatment of infectious diseases and colds with research supporting these applications (16).

Nervous system

Thuja has long been seen as a nervine and was used alongside oatstraw (Avena sativa) to support the nervous system (11). More recently it has been classified as a nervine with tonic and stimulant actions (11,13,15).

Reproductive system

Thuja stimulates uterine muscles which is the reason for its contraindication in pregnancy, as this may cause abortion. This stimulant action is useful in treating amenorrhoea and thuja has had further traditional use in treating uterine carcinomas. It is recommended for reducing the size of fibroids and lesions in endometriosis. It is also prescribed for reducing prostatic enlargement (2,15).

Respiratory system

Hoffmann suggests painting nasal polyps daily with the fluid extract of thuja, in combination with a nasal snuff to shrink them (4). Thuja is listed as a stimulant to mucous and serous membranes with an expectorant action. This also recommends the herb for treating sinusitis (15,2) .

Musculoskeletal system

The traditional use as an analgesic for rheumatic and arthritic pain is still relevant today (17). It is indicated more specifically for the extreme pain from sensitivity in gout, and thuja has been combined with other herbs such as burdock root (Arctium lappa), celery seed (Apium graveolens) and yarrow (Achillea millefolium) to provide relief (4).

Skin

Hoffmann suggests thuja as an antimicrobial application for use in eczema and itchy skin conditions, such as psoriasis (4). Molluscum contagiosum, tinea, warts and verrucas are also addressed by the antiviral properties of thuja (15). Thuja can be used in salves for healing wounds, bedsores, and cancerous ulcers.

Urinary system

Thuja has traditional recognition as a diuretic with a strong influence on the urinary system and has been prescribed for urinary infections, bed-wetting and urethritis. In the case of treating urinary incontinence, the effect is most helpful when it is due to lack of muscle tone (13,15,2).

-

Research

Thuja (Thuja occidentalis) Thuja occidentalis (Arbor vitae): A review of its pharmaceutical, pharmacological and clinical properties

There have been many reviews of the mode of action of thuja, but no controlled trials of the herb when used alone. Clinical studies have used extracts of Thuja occidentalis and other immunostimulants, demonstrating safety in respiratory tract infections. In vitro and in vivo studies have shown the antiviral and immunostimulant effects with cytokine and antibody production and activation of macrophages. Mice have commonly been used for in vivo trials, rats and rabbits less often. More clinical studies are indicated and needed. Several studies have looked at use of thuja and its antimetastatic action (18).

Effect of Thuja occidentalis and its polysaccharide on cell-mediated immune responses and cytokine levels of metastatic tumor-bearing animals

In this article, mice were administered with thuja occidentalis extract and its polysaccharide (TPS) to test the ability of the immune cells to maintain antitumour activity in the microenvironment of a metastatic tumour. Metastasis was injected into a tail vein of each mouse and effector mechanisms studied. The effect of Thuja occidentalis extract and TPS on pro-inflammatory cytokines and tissue inhibitor matrix metalloproteinases (TIMP) levels were also analysed.

It was found that the actions of natural killer (NK) cells were enhanced and antibody-dependent cell and complement-mediated cytotoxicity increased earlier than in control animals. Additionally, pro-inflammatory cytokines were lowered and anti-tumour factors elevated by the treatment with thuja. It was concluded there were clear indications that Thuja occidentalis and TPS were effective at stimulating the cell-mediated immune system and decreasing inflammation as well as inhibiting metastasis of tumour cells (19).

A further area of pertinent interest for prescribing thuja is in actions within the reproductive system. The following research, although on rats and using the essential oil and α-thujone rather than orally administered extract of thuja, may give some indication of support for the current practice of treating polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) by herbalists.

Thuja occidentalis L. and its active compound, α-thujone: Promising effects in the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome without inducing osteoporosis

Rats with letrozole-induced PCOS received the oil of Thuja occidentalis and its constituent α-thujone for 21 days. They were then sacrificed and blood samples were taken by cardiac puncture.

The results of testing demonstrated that estradiol and progesterone levels significantly increased, while luteinizing hormone (LH) and testosterone levels decreased in the T. occidentalis- and α-thujone-administered groups. The plasma low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C), leptin, and glucose concentrations were also significantly decreased in the T. occidentalis and α-thujone groups when compared to the control group. Histopathological findings demonstrated that the T. occidentalis and α-thujone groups displayed good healing. It was concluded that T. occidentalis oil and α-thujone can be used for the treatment of PCOS without inducing osteoporosis (20).

Antidiabetic activity of Thuja occidentalis Linn.

In this study shade dried aerial part (twigs) of Thuja occidentalis were extracted in ethanol. Phytochemical investigations showed the presence of flavonoids (quercetin, kaempherol), tannic acids, polysaccharides and proteins. Wistar albino rats of either sex, weighing 175–220 g, were used. The animals were maintained as per the norms of IAEC and the experiments were cleared by IAEC and the local institutional ethical committee.

The animals were fasted for 18 hours and had induced diabetes by alloxan monohydrate (150 mg/kg, i.p) dissolved in sterile normal saline. Their diabetic state was confirmed when the blood sugar value was greater than 180 mg/dl. All the animals were randomly divided into the four groups with six animals in each group. Group A, B, and C were given vehicle, diabetic and standard drug (glibenclamide, 10 mg/kg per day p.o) control, respectively.

Treatment with the ethanolic fraction of thuja was started 48 hours after the alloxan injection. Blood samples were drawn at weekly intervals until the end of study (i.e. 3 weeks). Fasting blood glucose, blood glutathione estimation and body weight measurement were done on days 1, 7, 14 and 21 of the study. On day 21, blood was collected by cardiac puncture under mild ether anaesthesia from overnight fasted rats and fasting blood sugar was estimated.

Serum cholesterol, serum triglycerides, serum LDL, serum creatinine, serum urea and serum alkaline phosphatase levels were decreased significantly, and serum HDL levels were increased significantly in both standard and test drug. The conclusion drawn from the study was that it indicated the ethanolic fraction of Thuja occidentalis had shown good antidiabetic activity, with significant antihyperglycemic activities in alloxan induced hyperglycemic rats without significant change in body weight. It further showed improvement in the lipid profile along with serum creatinine, serum urea and serum alkaline phosphatase by enhancing the effect on cellular antioxidant defences to protect against oxidative damage (21).

-

Did you know?

There are five types of thuja, with T. plicata also having been investigated for medicine. Thuja plicata was known as the grandmother of the forest as it was often the oldest tree in the area. Such older trees have a huge capacity for photosynthesis and make more sugars than they need. They channel this extra food via the mushroom mycelium to nearby saplings, feeding them as a grandmother might care for her grandchildren (3).

Additional information

-

Botanical description

Thuja is a long-lived monoecious tree which can reach an age of over 800 years in its natural habitat in North America, and a height of between 15–20 metres. In Britain it rarely grows above nine metres tall. An evergreen conifer, it has a densely branched crown, growing to an initial pyramidal or conical shape. The flattened twigs grow on slender branches slanted to be horizontal. The small leaves are 2.5 mm thick, a paler green and glandular on the underside. They resemble feathers on wings, laid thickly one on another and appear scaly and matted. When touched they give a strong scent described variously as resinous, camphoraceous or like apples.

Swathes of spreading slender branches lean outwards almost hiding the dark reddish orange bark of the trunk. The bark is smooth on a young tree but peels in long strips with age. The tiny flowers, yellow male and pinkish female are found on separate twigs and are followed by tiny 1 cm female cones sitting upright in clusters on strong shoots along the side of young branches. The seed cones, brown in autumn, mature in one season having four or six alternating pairs of woody scales with rounded scale tips. The seeds are oval. The wood is soft and fragrant from sparse resin cells, but resistant to decay (26,27,28).

-

Common names

- Arbor-vitae

- Tree of life

- White cedar

- Swamp cedar

- Hackmatack

-

Safety

Contraindicated in pregnancy and lactation. Associated with a substantial risk of causing foetal malformation. Not recommended during breastfeeding as there is potential toxicity from the essential oil. Do not exceed the recommended dose range. Caution with epilepsy (13,23,24,25).

-

Interactions

-

Contraindications

None known (23,24,25)

-

Preparations

- Liquid extract

- Tincture

- Ointment

-

Dosage

- Tincture (ratio 1:10 | 45%): 3–6 ml per day or (1:5) 1–3 ml per day (23)

- Fluid extract (1:1 | 50%): 2 ml three times per day (14)

- Infusion/decoction: 1–2 g by infusion three times per day (14)

-

Plant parts used

- Twigs

- Leaves

- Bark

-

Constituents

- Essential oil: α-thujone [31–65%], β-thujone [8–15%], fenchone [7–15%]. Essential oil content varies with the season and preparation (23)

- Coumarins: p-coumarinic acid, umbelliferone

- Flavonoids: Quercetin, kaempferol

- Proanthocyanidines: Procyanidin B 3

- Glycoproteins

- Polysaccharides (18)

-

Habitat

Thuja occidentalis is native to Northeastern America, and Southeastern Canada. It extends from the Gulf of St Lawrence to the southern part of James Bay and through central Ontario to southeastern Manitoba; then south and east to New Hampshire, and Maine. The species also grows locally in northwestern Ontario, west-central Manitoba, southeastern Minnesota, southern Wisconsin, north-central Illinois, Ohio, southern New England, and in the Appalachian Mountains. It is also recorded growing in Siberia.

Thuja grows well in a variety of soils with neither soggy nor very dry conditions. It is found in pastures and cool, moist sites which are nutrient rich. Growing both in fen areas and on loam over limestone or sandstone cliffs, the trees thrive in a neutral or slightly alkaline environment. The tree can be found up to 600 m above sea level (29).

-

Sustainability

Not currently on risk lists but complete data may be missing on the status of the species. Read more in our sustainability guide. Thuja occidentalis is not on the CITES endangered species list.

Thuja occidentalis is ranked as G5, secure, on Nature Server. [checked 2016] (30)

It is not listed on TRAFFIC.

IUCN listed Thuja occidentalis as least concern in 2011 (31)

However, an article from the Northern Journal of Applied Forestry written in 2009 on northern white-cedar ecology and silviculture in the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada states that white cedar sustainability is a concern due to regeneration failures, difficulty recruiting seedlings into sapling and pole classes, and harvesting levels that exceed growth. The authors conclude that because management of this resource has proven difficult, northern white-cedar silvicultural guidelines are needed throughout its range (32)

Habitat loss and over-harvesting from the wild are two of the biggest threats faced by medicinal plant species. There are an increasing number of well-known herbal medicines at risk of extinction. We must, therefore, ensure that we source our medicines with sustainability in mind.

The herb supplement industry is growing at a rapid rate and until recent years a vast majority of medicinal plant produce in global trade was of unknown origin. There are some very real and urgent issues surrounding sustainability in the herb industry. These include environmental factors that affect the medicinal viability of herbs, the safety of the habitats that they are taken from, as well as the welfare of workers in the trade.

The botanical supply chain efforts for improved visibility (transparency and traceability) into verifiably sustainable production sites around the world is now certificated through the emergence of credible international voluntary sustainability standards (VSS).

Read our article on Herbal quality & safety: What to know before you buy and Sustainable sourcing of herbs to learn more about what to look for and questions to ask suppliers about sustainability.

-

Quality control

Herbal medicines are often very safe to take; however, their safety and efficacy can be jeopardised by quality issues. So, it is important to buy herbal medicines from a reputable supplier, from sources known to test their herbs to ensure there is no contamination, adulteration or substitution with incorrect plant matter, as well as ensuring that recognised marker compounds are at appropriate levels in the herbs.

Some important quality assurances to look for are certified organic labelling, the correct scientific/botanical name, and the availability of information from the supplier about ingredient origins. A supplier should be able to tell you where the herbs have come from, what contaminants are not in the herb, and what the primary compounds are.

-

How to grow

It should be remembered that a full-size tree takes up a wide space in a garden. Thuja can be grown from seed sown in autumn or stratified before sowing (32). Grow in moist but well drained soil, being careful to protect young trees from drying winds. Trees are readily propagated by layering which can happen naturally in their native situation as branches lean down and root. Layering can be done in autumn or spring, or cuttings taken in September and planted in shade (26).

-

Recipe

Thuja infusion (Thuja occidentalis) Thuja prescription

The following prescription (100 ml) was given to treat a patient after her annual Pap smear showed cervical atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance. The treatment plan also included dietary advice and the suggestion of relaxation activities. The patient complied with the treatment and a repeat test after three months showed a normal result.

Prescription ingredients

- 40 ml Echinacea spp.

- 20 ml Glycyrrhiza glabra

- 20 ml Hypericum perforatum

- 15 ml Melissa officinalis

- 5 ml Thuja occidentalis

-

References

- Bone K. Functional Herbal Therapy : A Modern Paradigm for Western Herbal Clinicians. Stylus Publishing, London Aeon Books; 2021.

- Bone K. A Clinical Guide to Blending Liquid Herbs: Herbal Formulations for the Individual Patient. Churchill Livingstone; 2003.

- Cabrera C. Holistic Cancer Care. Storey Publishing, LLC; 2023.

- Hoffmann D. The New Holistic Herbal : A Herbal Celebrating the Wholeness of Life. Element; 1991.

- Larson DW. The paradox of great longevity in a short-lived tree species. Experimental Gerontology. 2001;36(4-6):651-673. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00233-3

- Frohne D, Pfänder HJ. A Colour Atlas of Poisonous Plants. Wolfe Publishing (SC); 1984.

- Holmes P. The Energetics of Western Herbs . Snow Lotus Press; 1998.

- Erichsen-Brown C. Medicinal and Other Uses of North American Plants : A Historical Survey with Special Reference to the Eastern Indian Tribes. Dover Publications; 1989.

- Finley Ellingwood. American Materia Medica, Therapeutics and Pharmacognosy. Theclassics Us; 2013.

- Bown D. The RHS Encyclopedia of Herbs & Their Uses. Dorling Kindersley; 1996.

- Lyle TJ. Physio-Medical Therapeutics, Materia Medica and Pharmacy. National Association of Medical Herbalists; 1932.

- Martindale W, Martindale WH, Westcott WW. The Extra Pharmacopoeia of Martindale and Westcott. London ; 1912.

- Weiss RF, Volker Fintelmann. Herbal Medicine. Thieme; 2000.

- Bartram T. Encyclopedia of Herbal Medicine. Robinson; 2015.

- British Herbal Medicine Association. British Herbal Pharmacopeia 1996. British Herbal Medicine Association; 1996.

- Menzies-Trull C. Herbal Medicine Keys to Physiomedicalism Including Pharmacopoeia. Faculty Of Physiomedical Herbal Medicine (Fphm; 2013.

- Kelly. Nursing Herbal Medicine Handbook. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

- Naser B, Bodinet C, Tegtmeier M, Lindequist U. Thuja occidentalis(Arbor vitae): A Review of its Pharmaceutical, Pharmacological and Clinical Properties. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2005;2(1):69-78. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecam/neh065

- Küpeli Akkol E, İlhan M, Demirel MA, Keleş H, Tümen I, Süntar İ. Thuja occidentalis L. and its active compound, α-thujone: Promising effects in the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome without inducing osteoporosis. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2015;168:25-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2015.03.029

- E.S. Sunila, Hamsa Thayele Purayil, Girija Kuttan. Effect ofThuja occidentalisand its polysaccharide on cell-mediated immune responses and cytokine levels of metastatic tumor-bearing animals. Pharmaceutical Biology. 2011;49(10):1065-1073. https://doi.org/10.3109/13880209.2011.565351

- Dubey S, Batra A. Anti diabetic activity of Thuja occidentalis Linn. Research Journal of Pharmacy and Technology. 2008;1(4):362-365.

- Romm A. Botanical Medicine for Women’s Health. London Elsevier Health Sciences; 2017.

- Mills S, Bone K. The Essential Guide to Herbal Safety. Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005.

- Natural Medicines Database. Thuja occidentalis. Therapeuticresearch.com. Published 2025. Accessed August 26, 2025. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/Data/ProMonographs/Thuja#safety

- Thomsen M. Phytotherapy Desk Reference. 6th ed. Aeon Books; 2022.

- Stapley C. The Tree Dispensary. Aeon Books; 2021.

- Rushforth KD. The Pocket Guide to Trees. Bounty Books; 2000.

- Conifer’s garden. Conifers Garden. Conifersgarden.com. Published 2025. Accessed August 26, 2025. https://conifersgarden.com/encyclopedia/thuja

- Nature Serve Explorer. NatureServe Explorer 2.0. explorer.natureserve.org. Published 2025. https://explorer.natureserve.org/Taxon/ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.145680/Thuja_occidentalis

- Group S. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Thuja occidentalis. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Published April 27, 2011. Accessed August 26, 2025. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/42262/2967995