-

How does it feel?

The bland, slightly sweet taste that is neither hot nor cold make poria an excellent herb for bringing things back to a neutral place. Sweet is the flavour that nourishes the centre in Chinese medicine, enhancing this ability to bring things into balance, while blandness drains dampness, meaning that poria can both relieve excess fluids obstructing the digestive system, while nourishing its deficiencies and facilitating the return to a tranquil state of mind.

-

What can I use it for?

Most of the therapeutic properties of fu ling come from its ability to promote urination and modulate the gut microbiota (1). This makes it useful for a variety of disorders relating to fullness, swelling and sensations of heaviness, regardless of whether these are physical manifestations, such as in oedema, or subjective sensations of fullness and distension in the epigastrium or bloating sensation in the abdomen (2,3). This dual effect also makes it ideal for firming the stool in cases of diarrhoea by eliminating some of the excess water.

By improving the gut microbiota and releasing excess fluids that are congesting the system, poria can also influence fatigue, oxidative stress, inflammatory responses and regulate blood sugar and lipid profiles, protecting the gut, liver and vascular tissues (4,5,6). This can also affect psychological wellbeing through the well-established link between the microbiome and neurocognitive disorders (7).

-

Into the heart of fu ling

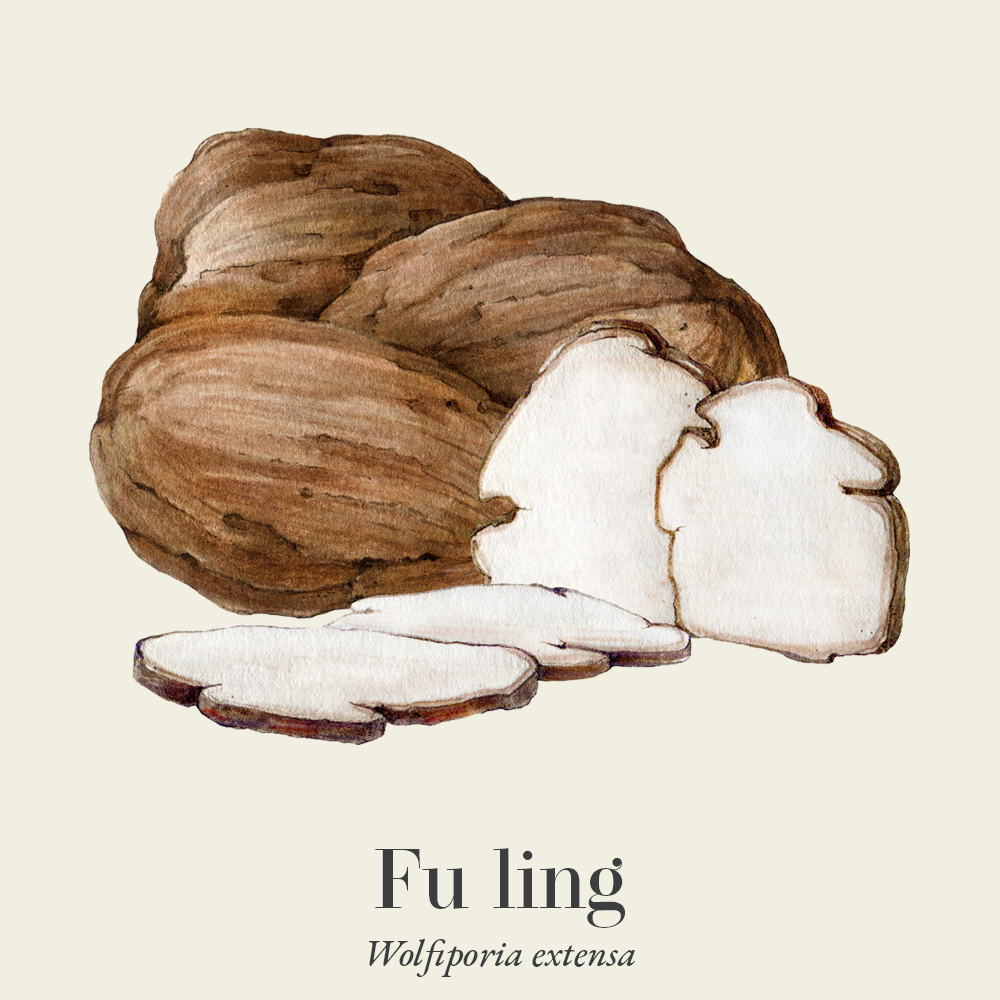

Fu Ling (Wolfiporia extensa) All of the functions of fu ling can be traced to its taste and properties in Chinese medicine. Its sweet taste fortifies the Spleen, while its blandness drains out dampness (2). The role of the Spleen is to transform and transport fluids, the failure of which results in the accumulation of dampness in the centre leading to feelings of fullness, bloating or swelling. This herb’s dual tonifying and draining properties make it ideal for dealing with this pathology by fortifying the Spleen’s deficiency, promoting its ability to manage fluids, while also leaching out the excess. The result is that fu ling can treat urinary dysfunction, swelling, bloating, and digestive disorders. It can also be applied to treat relating to the Heart and the spirit for example when the fluid builds up in the centre, and rises to oppress the Heart, for palpitations and anxiety, or when the Spleen fails to generate sufficient Blood to nourish the Heart.

This traditional logic also extends to different parts of the poria mushroom. When treating the Spleen, it is common to use the white part in the main body of the fungus (bai fu ling), while the nucleus, that grows directly around the pine root and often includes sections of the root itself (fu shen), has a stronger effect on soothing the Heart and calming the spirit (3). The reddish colour of the outer part near the skin (chi fu ling) provides it with an affinity for Heat patterns and the Blood so is often used for burning urination as a result of damp-heat or Blood stasis obstructions of the urinary tract (2). Meanwhile the very outer peel (fu ling pi) has the darkest colouration( blackish-brown).

Traditionally, dark colours are associated with the Kidneys, and therefore this part has the strongest effect on draining excess water to treat oedema and urinary conditions. Both of these outer parts have the strongest draining action, while the inner parts are the most tonifying, which corresponds with their constituents where the outer parts have the most triterpenoids with the most direct pharmacological action, while the main body is primarily polysaccharides that can modulate the gut microbiome (6).

-

Traditional uses

The main use of fu ling is to promote urination and drain dampness. All parts of the fungus are used for this, although the most powerful are the outer layers and the skin. It can be used for urinary difficulty, diarrhoea, oedema, or scanty urine (2,3).

Poria also strengthens the Spleen and harmonises the Middle Burner, for Spleen deficiency accompanied by dampness with symptoms such as loss of appetite, loose stools, fatigue and epigastric distension (2,3).

Poria also quietens the Heart and calms the spirit to treat palpitations, insomnia and forgetfulness. It can treat both excess patterns caused by turbid phlegm or dampness rising to obstruct the Heart, as well as patterns of Heart and Spleen deficiency (2,3).

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

Chinese energetics

-

What practitioners say

Urinary system

Urinary systemOne of the main functions of fu ling is to drain excess fluids from the body by promoting urination (2,3). In Chinese medicine, fluid pathologies can give rise to a wide range of disorders, as diverse as oedema, bloating, swellings, nodules, phlegm, arthritis and even clouded consciousness which are all perceived as accumulations of dampness in various locations (8). Poria can therefore be applied to treat all the aforementioned conditions.

It is often paired with pinellia (Pinellia ternata), whose drying and draining action on fluids complements and enhances the actions of poria for the treatment of chronic, stubborn disorders of fluid metabolism where the fluids have congealed into phlegm, seen in the classic formula Er Chen Tang, which serves as the basis for nearly all subsequent phlegm based formulas.

Digestive, endocrine and immune systems

The polysaccharide content of fu ling gives it a sweet taste and nourishing properties in Chinese medicine (2). However, many of these sugars act as prebiotics, modulating the microbiome to produce subtle but long lasting effects on a variety of conditions through a range of different actions, including antiobesity, antitumour, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory activities (6).

It achieves many of these effects by promoting the growth of intestinal bacteria that produce short chain fatty acids, which are involved in the regulation of blood glucose, energy metabolism and the prevention of obesity, diabetes, inflammatory conditions and tumour formation.

Nervous system

Dampness can also cloud the mind causing forgetfulness, confusion, anxiety and inability to concentrate, which is often treated with Settle the Emotions Pill (Ding Zhi Wan). In this formula it is combined with ginseng (Eleutherococcus senticosus), sweet flag (Acorus calamus) and yuan zhi (Polygala tenuifolia) root and serves the important function of draining the dampness which is obscuring the Spirit. This same function can lead to its inclusion in formulas where anxiety, insomnia and forgetfulness are due to a Blood deficiency, as in the formula Sour Jujube Seed Decoction (Suan Zao Ren Tang).

Here, it serves as an assistant to sour jujube seed, which strongly nourishes the Heart Blood but may lead to dampness if overconsumed. Therefore, poria assists in draining any dampness, whilst also strengthening the digestive system that is responsible for converting food, including herbs, into valuable fluids such as blood (2).

Musculoskeletal system

Dampness is also a common cause for the swelling of joints in Chinese medicine, making fu ling appear in many formulas for joint pain of the damp variety. In particular, it appears in the formula Fu Ling Wan (poria pill) where dampness accumulates in the centre, transforming into phlegm which then overflows into the channels causing pain and swelling in fixed locations that does not change with the weather and has a slow, chronic onset (9).

In modern terms, this may correspond to forms of arthritis that have their origin in metabolic disorders, displaying a classic Chinese strategy of treating the root by assigning a herb with no pain relieving properties as the chief herb in a formula for a painful condition.

-

Research

Fu Ling (Wolfiporia extensa) The role of Wolfiporia cocos (F. A. Wolf) Ryvarden and Gilb. polysaccharides in regulating the gut microbiota and its health benefits

This review looked at the polysaccharide content of Poria cocos and its role in regulating the gut microbiota, which are related to but different from the traditional pharmacological actions of its components. These polysaccharides offer an improvement in intestinal barrier function and a reduction in intestinal inflammation via short chain fatty acids. These provide an indirect but complementary approach to the more direct pharmacological actions of the triterpene components, for a more stable and integrated approach to treatment.

They also note that Poria cocos polysaccharides are divided into water soluble and alkali soluble varieties, the latter of which need to be processed through degradation into oligosaccharides, or carboxymethylating and sulfating, in order to improve bioavailability (6).

Benefits of herbal formulae containing Poria cocos (fu ling) for type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis

This systematic review included 73 randomised controlled trials, finding that the integration of herbal formulae containing poria with hypoglycaemic agents in type 2 diabetic patients resulted in lower fasting blood glucose, two-hour postprandial blood glucose and haemoglobin A1c, while also having lower adverse events reported. This indicated that the combined therapies were well tolerated and the combined use of poria with hypoglycaemic agents was supported but heterogeneity and poor reporting of the randomisation methods in many of the studies indicated caution when interpreting these results (5).

Molecular basis for Poria cocos mushroom polysaccharide used as an antitumour drug in China

This review examined 72 studies looking at polysaccharides extracted from Poria cocos in the treatment of tumours. They reported low toxicity and improved effects when combined with chemotherapy treatments, although their effects were largely related to biological markers and not survival rates or patient quality of life scores. They acknowledged that a major obstacle is a lack of clarity in the active ingredients involved in these effects and advocated for the development of better quality standards to create more consistent extracts.

These sentiments were echoed in an update to this review in 2024, which concluded that poria polysaccharides contained many potential health benefits, including antioxidant, immunomodulatory, neuroregulatory, antitumour, hepatoprotective and gut regulatory properties but many of their structures, mechanisms and effects on humans were still unknown (11).

Phytochemistry and pharmacological activities of Wolfiporia cocos

This review explored the pharmacology of poria, assessing its antitumour, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, nephroprotective, hepatoprotective and antibacterial effects, concluding that the triterpenes and polysaccharide fractions are promising agents for the treatment of disease or as functional foods, but acknowledged difficulties with yield, separation and purification of its active ingredients (12).

-

Did you know?

Despite being the most commonly used mushroom in Chinese medicine where it has been used as a functional food in China for over 2000 years, fu ling has received relatively little attention in other traditions, with the exception of native North Americans, who used it as a source of food during time of scarcity, giving it the common names of Tuckahoe and Indian bread (13).

Originally it was believed to be an outgrowth of the pine trees themselves, formed from the resin or a gas that was exuded from the roots (1). It was not until the 16th century that it was described as being a parasite and finally classified as a fungus in the 19th century.

Additional information

-

Botanical description

Poria cocos refers to the large, edible sclerotum of a saprotrophic polypore fungus that grows around the dead roots of pine trees (28).

-

Common names

- Poria

- Fu ling

- China root

- Indian bread

- Hoelen

- Tuckahoe

- Matsuhodo

-

Safety

No adverse effects have been recorded within normal dose ranges besides occasional allergic reactions with symptoms of pruritis, papular rashes, achy extremities, vertigo and nausea (2). Contact with the powdered drug may also cause allergic asthma, symptoms of hayfever, tachypnoea and cold sweats.

At doses 500 times the normal adult dose, a slight decrease in body weight and increase in white blood cell counts has been observed (3).

-

Interactions

No interactions have been documented, although it may be prudent to avoid concurrent use with other diuretics (3).

-

Contraindications

Traditional contraindications include urinary dribbling, incontinence or spermatorrhoea due to Kidney deficiency since its ability to mobilise water can fatigue the Kidneys (2). This applies to both yin and yang deficiency. Caution is also recommended in sunken Spleen qi with symptoms such as prolapse or haemorrhoids, as its downward draining action may enhance this sinking tendency (2,3).

-

Preparations

- Thinly sliced: Increases the surface area making it best for decoctions.

- Square sliced: 1–2 cm squares of poria sclerotum. These may be powdered and made into pills but are not ideal for decoctions since the water often fails to penetrate to the centre of the block.

- Dry frying or baking: Enhances its ability to strengthen the digestion (Spleen)

- Cinnabar coated: A traditional method of enhancing its spirit calming properties but rarely done now and should be avoided due to the toxicity of cinnabar.

-

Dosage

- Tincture (ratio 1:3| 45%): Take between 5–15 ml three times daily (16)

- Fluid extract (1:1 | %): Take between 40–80 ml per week (16)

- Infusion / decoction: 9–15 g (2,3); 9–30 g of the main body or core, or 6–15 g of the outer sclerotum, or 15–30 g of peel (17)

-

Plant parts used

- White part of the main sclerotium (bai fu ling)

- The sclerotium directly surrounding and including the pine root (fu shen)

- Red part near the outer skin (chi fu ling)

- Dark outer peel (fu ling pi)

-

Constituents

- Triterpenes

- Pachymic acid: The main quality indicator of poria, unique to poria cocos and which should be present at a minimum quantity of 0.04% of dried material (16,18). It has cytotoxic, anti‑inflammatory, antihyperglycemic, antiviral, antibacterial, sedative‑hypnotic, and anti‑ischemia/reperfusion activities but its bioavailability is limited by poor water solubility (19).

- Polyporenic acid C: The main quality indicator for poria peel which should be present at a minimum quantity of 0.1% (16). It is best known for its potential to induce apoptosis in lung cancer cells through the caspase-8 pathway (19), but it has also been implicated in metabolic and anti-ageing pathways and modulation of blood lipid and glucose profiles through inhibition of bile acid uptake transporters and α-glucosidase (21,22,23,24).

- Tumulosic acid: Several forms may regulate blood sugar through the inhibition of α-glucosidase and lipid profiles through the inhibition of bile acid uptake transporters (23,24).

- Trametenolic acid: Some forms may regulate blood sugar through the inhibition of α-glucosidase (24).

- Poricoic acids: A group of triterpenes, some of which may regulate blood sugar through the inhibition of α-glucosidase and lipid profiles through the inhibition of bile acid uptake transporters (23,24).

- Polysaccharides

- β-pachyman: the principal polysaccharide found in poria, a β-glucan with poor water solubility but decent antitumour activity (18). Also referred to as pachymose in older literature where it was found to constitute up to 84% of the total content of dried weight (25).

- Pachymaran: β-pachyman with the glucose side chains removed that improves water solubility (18).

- Glucan H11: One of the first polysaccharides with antitumour activity isolated from poria in 1983, which appears to work through a host-mediated pathway rather than blocking tumour growth directly (18).

- Sterols: Ergosterol provides membrane structure and fluidity in fungi, and is also the precursor to vitamin D2, which is formed when exposed to ultraviolet light (26).

- Cholines: Choline is an essential nutrient required for the synthesis of neurotransmitter acetylcholine and which is the strongest promoter of neuronal differentiation and most abundant constituent in poria (27).

- Triterpenes

-

Habitat

Poria cocos grows mainly in subtropical east and southeast Asia, but also in North America (18,28). Around 70% of the cultivation area for poria is found within China, mainly in the areas south of the Yangtze river although it can be cultivated throughout Asia, Americas, Oceania and Africa (1).

-

Sustainability

Not currently on risk lists but complete data may be missing on the status of the species. Read more in our sustainability guide. Fu ling was originally cultivated by inoculating pine logs and burying them in sandy soil. This method, however, resulted in deforestation and affected the local ecosystem. Overharvesting and habitat destruction reduced the biodiversity of pine forests in southern China (29). Recent cultivation methods, however, are through substrate bags and pine sawdust, which is a more sustainable method of cultivation (30).

Habitat loss and over-harvesting from the wild are two of the biggest threats faced by medicinal plant species. There are an increasing number of well-known herbal medicines at risk of extinction. We must, therefore, ensure that we source our medicines with sustainability in mind.

The herb supplement industry is growing at a rapid rate and until recent years a vast majority of medicinal plant produce in global trade was of unknown origin. There are some very real and urgent issues surrounding sustainability in the herb industry. These include environmental factors that affect the medicinal viability of herbs, the safety of the habitats that they are taken from, as well as the welfare of workers in the trade.

The botanical supply chain efforts for improved visibility (transparency and traceability) into verifiably sustainable production sites around the world is now certificated through the emergence of credible international voluntary sustainability standards (VSS).

Read our article on Herbal quality & safety: What to know before you buy and Sustainable sourcing of herbs to learn more about what to look for and questions to ask suppliers about sustainability.

-

Quality control

Pachymic acid is the main marker compound for assessing the quality of poria, and should be present in quantities of 0.04% in the sclerotum (fu ling), 0.05% in the core (fu shen) and outer sclerotum (chi fu ling) (15). The peel should contain not less than 5.0% of dilute ethanol-soluble extractives and not less than 3.0% of water extractives and not less than 0.1% of polyporenic acid C (15).

-

How to grow

Fu ling is a wood decay fungus that has been artificially cultivated for over 1500 years during the Southern and Northern Dynasties (420–589 CE) (1). Today, three main cultivation methods are practiced: It can be cultivated on pine segments, on pine stumps, or by using a substitute. It is usually harvested in autumn, after 9–12 months of growth, when the sclerotia epidermis is yellowish-brown with no white cracks (31).

-

Recipe

Fu Ling (Wolfiporia extensa) Poria, cinnamon, atractyloides and liquorice decoction

The pairing of poria and cinnamon is the basis of a number of classical Chinese formulas that treat circulatory disorders which cause fluid accumulation, first recorded by the famous Han Dynasty physician Zhang Zhongjing (c. 200 CE). A number of formulas based on this pairing have been in continuous use since and contemporary research suggests that this pair targets inflammatory pathways involved in coronary heart disease (14).

The classical indications for this formula include fullness below the heart, surging palpitations, dizziness upon standing and a sunken pulse; or shortness of breath with mild rheum; or phlegm-rheum under the heart with tightness of the chest and ribs and dizziness (15). Most of the herbs in this formula nourish the Spleen, which governs fluid metabolism, with the role of poria being central to directing this action towards the draining of accumulated fluids downwards through the urine, while also having a capacity to calm heart palpitations (9).

Ingredients

- 12 g poria

- 9 g cinnamon twigs

- 12 g white atractyloides

- 6 g honey fried liquorice

- 500 ml filtered water

How to make a fu ling decoction

- Place all ingredients into a saucepan and cover with water.

- Bring to the boil and reduce the heat.

- Simmer gently for 15 minutes.

- Strain and drink three cups per day.

Four gentlemen decoction

This formula derives from the Taiping era (12th century) and is identical to the previous, except it exchanges cinnamon for ginseng. This single alteration changes the focus of the formula towards strengthening the ability of the body to acquire energy from digestion (Spleen qi), and so is indicated for symptoms of pallid complexion, fatigue, reduced appetite, sensitive digestion and weakness in the limbs, usually accompanied by a pale, swollen tongue and weak pulse (9).

Ingredients

- 9 g ginseng

- 9 g poria

- 9 g white atractyloides

- 6 g honey fried liquorice

How to make a four gentlemen decoction

- Place all ingredients into a saucepan and cover with water.

- Bring to the boil and reduce the heat.

- Simmer gently for 15 minutes.

- Strain and drink three cups per day.

- Fresh ginger (Zingiber officinale) and jujube berries (Zizhyphus jujube) are also often added.

-

References

- Lei J, Gong D, Duan L, et al. A multidimensional perspective on Poria cocos, an ancient fungal traditional Chinese medicine. J Ethnopharmacol. 2025;348:119869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2025.119869

- Bensky D, Clavey S & Stoger E. Chinese Herbal Medicine: Materia Medica, 3rd Edition. Seattle: Eastland Press. 2004.

- Chen JK & Chen TT. Chinese Medical Herbology and Pharmacology. Art of Medicine Press. 2012.

- Zhou X, Li Y, Yang Y, et al. Regulatory effects of Poria cocos polysaccharides on gut microbiota and metabolites: evaluation of prebiotic potential. NPJ Sci Food. 2025;9(1):53. Published 2025 Apr 22. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41538-025-00416-91

- Di YM, Sun L, Lu C, et al. Benefits of herbal formulae containing Poria cocos (Fuling) for type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2022;17(12):e0278536. Published 2022 Dec 1. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0278536

- Lai Y, Lan X, Chen Z, et al. The Role of Wolfiporia cocos (F. A. Wolf) Ryvarden and Gilb. Polysaccharides in Regulating the Gut Microbiota and Its Health Benefits. Molecules. 2025;30(6):1193. Published 2025 Mar 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30061193

- Song M, Zhang S, Gan Y, Ding T, Li Z, Fan X. Poria cocos Polysaccharide Reshapes Gut Microbiota to Regulate Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Alleviate Neuroinflammation-Related Cognitive Impairment in Alzheimer’s Disease. J Agric Food Chem. 2025;73(17):10316-10330. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.5c01042

- Clavey S. Fluid Physiology and Pathology in Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2nd Edition. Churchill Livingstone. 2002.

- Scheid V, Bensky D, Ellis A, Barolet R. Chinese Herbal Medicine: Formulas & Strategies 2nd edition. Seattle: Eastland Press. 2009.

- Li X, He Y, Zeng P, et al. Molecular basis for Poria cocos mushroom polysaccharide used as an antitumour drug in China. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23(1):4-20. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.13564

- Ng CYJ, Lai NPY, Ng WM, Siah KTH, Gan RY, Zhong LLD. Chemical structures, extraction and analysis technologies, and bioactivities of edible fungal polysaccharides from Poria cocos: An updated review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;261(Pt 1):129555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.129555

- Nie A, Chao Y, Zhang X, Jia W, Zhou Z, Zhu C. Phytochemistry and Pharmacological Activities of Wolfiporia cocos (F.A. Wolf) Ryvarden & Gilb. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:505249. Published 2020 Sep 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.505249

- Wu F, Li SJ, Dong CH, Dai YC, Papp V. The Genus Pachyma (Syn. Wolfiporia) Reinstated and Species Clarification of the Cultivated Medicinal Mushroom “Fuling” in China. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:590788. Published 2020 Dec 15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.590788

- Duan B, Han L, Ming S, et al. Fuling-Guizhi Herb Pair in Coronary Heart Disease: Integrating Network Pharmacology and In Vivo Pharmacological Evaluation. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2020;2020:1489036. Published 2020 May 17. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/1489036

- Liu G. Discussion of Cold Damage (Shang Han Lun): Commentaries and Clinical Applications. 2015. London: Singing Dragon.

- Thomsen M. Phytotherapy Desk Reference. 6th ed. Aeon Books; 2022.

- Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan. Taiwan Herbal Pharmacopeia 4th Edition, English Version. Taiwan: Ministry of Health of Welfare. 2022.

- Wei C, Wang H, Sun X, et al. Pharmacological profiles and therapeutic applications of pachymic acid (Review). Exp Ther Med. 2022;24(3):547. Published 2022 Jul 1. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2022.11484

- Ling H, Zhou L, Jia X, Gapter LA, Agarwal R, Ng KY. Polyporenic acid C induces caspase-8-mediated apoptosis in human lung cancer A549 cells. Mol Carcinog. 2009;48(6):498-507. https://doi.org/10.1002/mc.20487

- He J, Yang Y, Zhang F, et al. Effects of Poria cocos extract on metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease via the FXR/PPARα-SREBPs pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1007274. Published 2022 Oct 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.1007274

- Ke H, Zhang X, Liang S, et al. Study on the anti-skin aging effect and mechanism of Sijunzi Tang based on network pharmacology and experimental validation. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024;333:118421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2024.118421

- Cai H, Cheng Y, Zhu Q, et al. Identification of Triterpene Acids in Poria cocos Extract as Bile Acid Uptake Transporter Inhibitors. Drug Metab Dispos. 2021;49(5):353-360. https://doi.org/10.1124/dmd.120.000308

- Ma C, Lu J, Ren M, et al. Rapid identification of α-glucosidase inhibitors from Poria using spectrum-effect, component knock-out, and molecular docking technique. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1089829. Published 2023 Aug 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2023.1089829

- Read BE, Wong SY. Chemical Analysis and Physiological Properties Fuh-Ling. Chin Med J. 1925; Apr 1: 314 – 320. Accessed 25 September 2025. https://mednexus.org/doi/abs/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.1925.04.104

- Rangsinth P, Sharika R, Pattarachotanant N, et al. Potential Beneficial Effects and Pharmacological Properties of Ergosterol, a Common Bioactive Compound in Edible Mushrooms. Foods. 2023;12(13):2529. Published 2023 Jun 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12132529

- Jiang X, Hu Z, Qiu X, et al. Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf, a Traditional Chinese Edible Medicinal Herb, Promotes Neuronal Differentiation, and the Morphological Maturation of Newborn Neurons in Neural Stem/Progenitor Cells. Molecules. 2023;28(22):7480. Published 2023 Nov 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28227480

- Wang L, Wang Q, Wang Y, Wang Y. Comparison of Geographical Traceability of Wild and Cultivated Macrohyporia cocos with Different Data Fusion Approaches. J Anal Methods Chem. 2021;2021:5818999. Published 2021 Jul 21. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5818999

- Lee S, Lee D, Lee SO, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of the sclerotia of edible fungus, Poria cocos Wolf and their active lanostane triterpenoids. J Funct Foods. 2017;32:27-36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2017.02.012

- Lei J, Gong D, Duan L, et al. A multidimensional perspective on Poria cocos, an ancient fungal traditional Chinese medicine. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2025;348:119869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2025.119869

- Jiang Y, Ren A, Sun X, Yang B, Peng H, Huang L. Fuling production areas in China: climate and distribution changes (A.D. 618–2100). Frontiers in plant science. 2024;15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2024.1289485

- Joconn. Example of specific cultivation method of Poria cocos. Joconnmushroom.com. Published 2025. Accessed October 24, 2025. https://www.joconnmushroom.com/video/example-of-specific-cultivation-method-of-poria-cocos.html