-

How does it feel?

Boneset is a bitter herb with a predominantly diaphoretic action (1). Its effects are most apparent in acute febrile states, where it supports sweating and assists in the regulation of body temperature (2). Taken as a hot infusion, it acts to relieve the heaviness, aching, and congestion associated with influenza and similar infections (1).

-

What can I use it for?

Boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum) Boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum) is used in the management of acute infectious and febrile conditions, particularly influenza and influenza-like illnesses (3). It is indicated where symptoms include fever, chills, profound fatigue, and deep musculoskeletal aching (1,3). Its primary application is during the early stages of acute illness, where it supports diaphoresis and assists the body in regulating temperature and resolving fever. Boneset is not used as a long-term immune tonic but rather as a short-term medicine during acute infection.

Boneset is also used to support immune function during acute illness (1). Its polysaccharides have been shown to influence immune activity, including enhancement of phagocytosis, while the sesquiterpene lactones contribute to its anti-inflammatory action (4,5). These actions support its use in infections characterised by systemic involvement (like fever and general malaise) and inflammatory symptoms (1,6). Although some constituents demonstrate cytotoxic activity in vitro, boneset is not used clinically as a herb with antitumour properties (7).

In the respiratory system, boneset is used for acute conditions involving fever and congestion of the respiratory mucosa (1,3).Taken as a hot infusion, it is used in influenza, acute bronchitis, nasopharyngeal catarrh, colds, coughs and allergic rhinitis (1,8). Its diaphoretic and mild expectorant actions assist in clearing congestion and supporting the resolution of respiratory symptoms associated with infection.

Boneset can also be used to improve digestion. In small doses, its bitterness supports digestion, relieving indigestion, wind and bloating (1,3). In larger doses, its bitter principles can contribute to a laxative effect and mild hepatic stimulation, supporting elimination during short-term use (1). These actions support its use in conditions associated with metabolic congestion, such as inflammatory joint conditions and certain skin disorders (1).

-

Into the heart of boneset

Boneset carries a distinctly bitter, cooling and drying energetic profile, with an affinity for conditions of cold, stagnation and systemic congestion. Its action moves inward and downward, engaging the core of the body rather than acting superficially. This makes it particularly suited to conditions that feel heavy and exhausting, where fever struggles to resolve and pain penetrates deeply. The plant’s bitterness supports its capacity to stimulate hepatic processes, while its diaphoretic action and heat encourage movement, circulation and release (2).

-

Traditional uses

Boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum) Boneset has a long history of use in North America, particularly among Indigenous peoples of the eastern woodlands, where it was regarded as an important remedy for fever and systemic illness (6). Native American tribes used the plant extensively for influenza, febrile conditions, and severe musculoskeletal pain (1,6). The common name “boneset” reflects its traditional use in illnesses where pain was described as penetrating ‘to the bones’, such as severe influenza and other high-fever conditions.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, boneset was adopted into European-American medical practice and became a well-established remedy in Eclectic and Physiomedical medicine. It was used in the treatment of intermittent fevers, including malaria, as well as serious infectious diseases such as typhoid and yellow fever (3,6). Boneset appeared in the United States Pharmacopoeia from 1820 until 1916, where it was classified as a stimulant and diaphoretic, reflecting its perceived ability to promote sweating and support the resolution of fever during acute illness (6).

In addition to its role in febrile conditions, boneset was traditionally used for muscular rheumatism, dyspepsia, and digestive weakness, particularly in older adults (1). Its bitter properties were used to improve digestive function and appetite during convalescence. Other historical applications included the treatment of cutaneous diseases and the elimination of intestinal parasites, such as tapeworm (1).

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

-

What practitioners say

Respiratory system

Respiratory systemBoneset is widely recognised for its effects on the respiratory system. It has been used for influenza, acute bronchitis, and fevers accompanied by deep body aches, and was even used successfully during yellow fever outbreaks according to Bartram (6). For children with colds or feverishness, it is often combined with yarrow (Achillea millefolium) or elderflower (Sambucus nigra) and traditionally administered three times daily (6).

It is also indicated for conditions such as nasopharyngeal catarrh or influenza with congested respiratory mucosa and pronounced aching (3). A hot infusion is considered the most effective way to promote diaphoresis and sweating, supporting the body’s natural response to fever (3). Hot infusions are also used to ease symptoms of allergic rhinitis, bronchitis, catarrh, colds, and coughs, and externally, a tea made from boneset can be applied to the skin to help reduce fevers (1).

Immune system

Boneset is indicated for flu as it promotes sweating, clears heat, and helps the body eliminate toxins (1). Laboratory studies suggest that its polysaccharides and sesquiterpene lactones can enhance white blood cell production and stimulate phagocytosis, providing measurable immune support (1). It also has anti-inflammatory properties, and some constituents, including sesquiterpene lactones and eupatorin, exhibit cytotoxic activity in vitro, although these effects are not applied clinically (1).

Digestive system

The bitterness of boneset can lead to a laxative effect, especially when used in larger doses, supporting digestive function (3). Because of boneset’s bitter compounds, this herb can relieve indigestion, bloating, wind and spasmodic abdominal pain (1). Additionally, boneset supports the body’s elimination processes through mild hepatic stimulation, and asa mild laxative, which explains its traditional use in arthritis, skin conditions and intestinal worms (1).

-

Research

Boneset (Eupatorium perfoliatum) Research into the effects of boneset in humans has not been conducted.

Eupatorium perfoliatum counteracts TNF-α mediated pathogenesis in chikungunya virus infection (9)

This study aimed to evaluate whether an ultradiluted hydroethanolic preparation of Eupatorium perfoliatum could counteract TNF-α-mediated pathogenic processes in chikungunya virus (CHIKV) infection, focusing on inflammatory mechanisms rather than direct antiviral effects.

No human participants were involved; the research was conducted using in silico molecular docking, in vivo transcriptional and translational analyses, and in vitro cytopathic assays in experimental models to simulate disease processes and treatment effects. The primary outcome was reduction of TNF-α transcription and translation levels, with secondary outcomes including lowered expression of hub genes implicated in CHIKV pathogenesis and reduced cytopathic effects following infection.

Results showed strong predicted molecular interactions between boneset’s constituents and TNF-α, and treatment with the candidate preparation was associated with lowered TNF-α expression, attenuation of inflammatory pathology, and reduced cytopathic impacts in the models used, suggesting potential to modulate inflammation linked to CHIKV pathogenesis (9).

Anti-inflammatory activity of Eupatorium perfoliatum L. extracts, eupafolin, and dimeric guaianolide via iNOS inhibitory activity and modulation of inflammation-related cytokines and chemokines

This study investigated the anti-inflammatory effects of Eupatorium perfoliatum extracts and isolated compounds (eupafolin and a dimeric guaianolide) using LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophage cells (in vitro). The extracts and compounds were tested for inhibition of nitric oxide (NO) production and modulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines.

The dichloromethane extract and the isolated compounds showed significant inhibition of NO and reduced expression of cytokines including IL-1α, IL-1β, CCL2, CCL22, and CXCL10, while TNF-α was moderately affected. These results demonstrate measurable anti-inflammatory activity at the cellular level, providing experimental support for boneset’s traditional use in inflammatory conditions, although no human or animal subjects were involved (10).

Antiviral activity of hydroalcoholic extract from Eupatorium perfoliatum L. against the attachment of influenza A virus

This study investigated the antiviral activity of hydroalcoholic extracts from Eupatorium perfoliatum against influenza A virus in MDCK II cells (in vitro). No human participants were involved. The extract was tested for its ability to inhibit viral attachment, plaque formation, and hemagglutination. It significantly reduced viral binding and plaque formation at concentrations of ~1–10 µg/mL, with low cytotoxicity, and high-molecular-weight polyphenols were identified as likely active compounds.

These results suggest that boneset extracts can inhibit influenza A virus attachment in cell culture, supporting further investigation as a potential antiviral agent (11).

-

Did you know?

The name Eupatorium perfoliatum comes from the unique way its leaves grow. The stem appears to pass through a single pair of joined leaves, a feature called “perfoliate” leaves, which is uncommon and makes the plant easy to identify in the wild (12).

Additional information

-

Botanical description

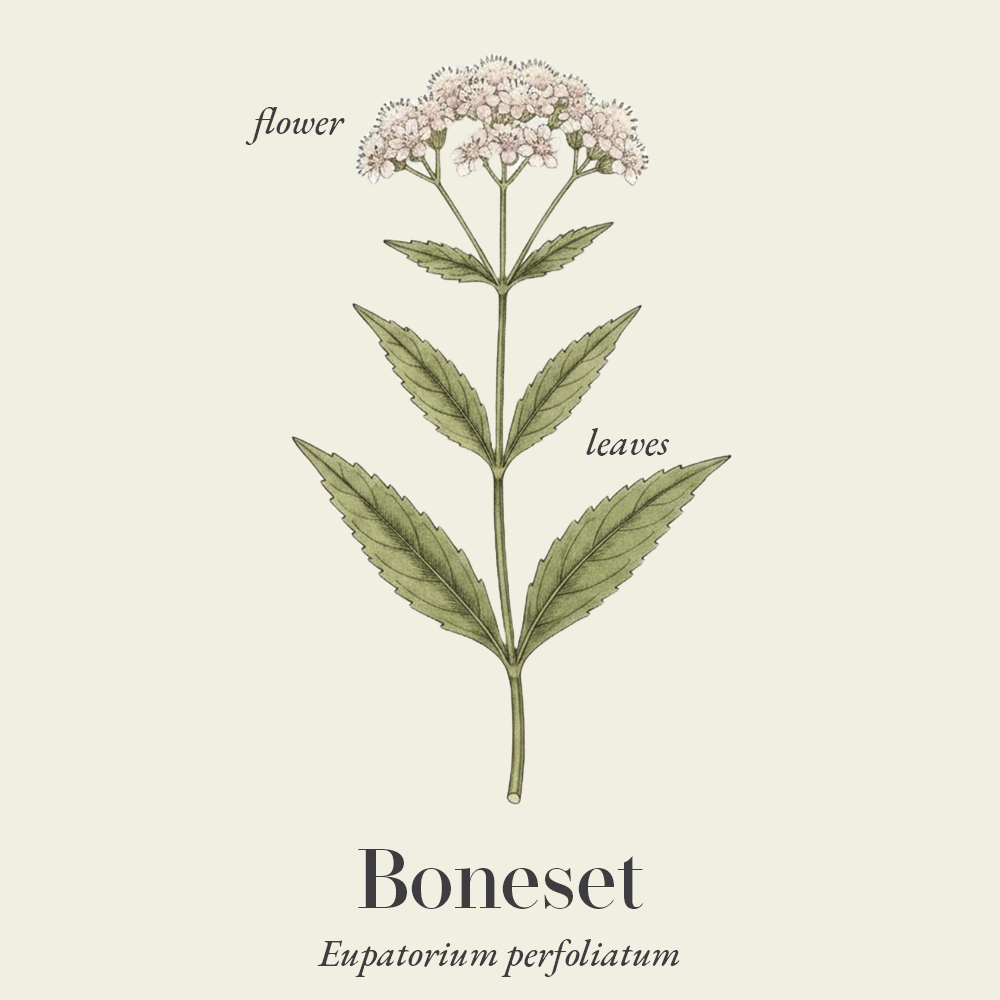

Boneset is a perennial herb in the Asteraceae family, growing 0.6–1.8 m tall with erect, branching, hairy stems. It arises from a fibrous root system and is found in moist habitats such as marshes, wet meadows and stream banks.

The leaves are opposite, lance-shaped to triangular, with serrated margins. Mid- and lower-stem leaves are perfoliate, with their bases joined around the stem, giving the appearance that the stem passes through the leaf. Stems are green and hairy, sometimes reddish at the base.

White flowers are grouped in flat-topped or slightly convex clusters (corymbs) at the ends of stems from mid-summer to early fall. Each cluster contains 9–23 small disk flowers. The fruit is a small, dry achene with fine hairs that helps wind dispersal (13).

-

Common names

- Boneset

- Feverwort

- Thoroughwort (1, 3, 6, 13)

-

Safety

Boneset contains pyrrolizidine alkaloids (PAs), which are potentially toxic compounds that can cause liver damage with long-term or excessive use, making caution essential when considering extended use (15,16).

There is no information on safety during pregnancy and breastfeeding, but due to the PA content, it is not recommended during pregnancy or breastfeeding. Large doses may cause gastrointestinal upset, including vomiting and diarrhoea (1).

-

Interactions

None described (1,15,16)

-

Contraindications

None known (1,8,15)

-

Preparations

- Hot infusion

- Ethanolic extract (tincture)

- Powder or capsules

-

Dosage

- Tincture (1:5 | 45%): 1–4 ml a day (3,8)

- Fluid extract (1:1 | 25%): 1–2 ml per day (3)

- Infusion/decoction: 0.7–2 g per day, one heaped teaspoon to each cup boiling water, infuse 5–20 minutes (6,8). Drink half to one cup every two hours if needed for acute or three times daily if chronic (6)

- Powder: 375 mg (quarter of a teaspoon) (6)

-

Plant parts used

Aerial parts (1)

-

Constituents

- Sesquiterpene lactones: Eupafolin, euperfolitin, eufoliatin, eufoliatorin, euperfolide, eucannabinolide and helenalin (3)

- Polysaccharides: 4-O-methylclucuroxylans (1,3,8)

- Flavonoids: Eupatorin, astragalin, kaempferol, quercetin, hyperoside, rutin (1,3)

- Diterpenes (1,3)

- Phytosterols (3,8)

- Volatile oils (1,3,8)

- Tannins (1,8)

- Caffeic acids (14)

- Alkaloids: Pyrrolizidine alkaloids (1)

-

Habitat

It is native to North America from Nova Scotia to Florida, Louisiana, Texas and North Dakota, growing in moist woods or thickets (3). It thrives in moist to wet environments such as marshes, wet meadows, stream banks, and low prairies (12). The plant prefers full to partial sunlight and is commonly found in open, damp areas where the soil remains consistently moist.

-

Sustainability

Eupatorium perfoliatum was most recently been assessed for The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species in 2015 and is listed as Least Concern (17). It appears in NatureServe Explorer with a G5 (secure) global conservation status, indicating that the species is widespread, abundant and not at risk of extinction across its range (eastern North America) (18).

There are no records of boneset being monitored or listed by TRAFFIC (the organisation that tracks trade in wildlife species), suggesting it is not a species of concern in international trade monitoring (19). Boneset is not listed on Species+, meaning it is not protected under Multilateral Environmental Agreements like CITES (20).

Read our article on Herbal quality & safety: What to know before you buy and Sustainable sourcing of herbs to learn more about what to look for and questions to ask suppliers about sustainability.

-

Quality control

Boneset is harvested from both wild and cultivated sources for medicinal use. Analyses show variation in toxic alkaloid content among samples, possibly due to hybridisation or contamination with related species (15). Authentication and quality control are important to avoid adulteration and ensure correct botanical identity.

-

How to grow

Boneset can be propagated from seed or by root division. Spring growth is slow, but the plant is frost-resistant and tolerant of periods of drought (3). It prefers moist, rich soils and full to partial sunlight. The aerial parts are harvested during or just before flowering for medicinal use, when the concentration of active constituents is highest (3).

-

Recipe

Boneset infusion

A hot infusion of Eupatorium perfoliatum aerial parts, traditionally prepared to support sweating and respiratory ease in acute febrile conditions. The bitter infusion is taken warm in small quantities.

Ingredients

- 1–2 teaspoons dried boneset aerial parts

- 250 ml boiling water

How to make a boneset infusion

- Place the dried boneset in a teapot or heat-proof cup.

- Pour 250 ml of boiling water over the herb.

- Cover and steep for 10–15 minutes.

- Strain and drink while warm.

- Repeat up to 2–3 times daily when needed.

-

References

- McIntyre A. The Complete Herbal Tutor: The Definitive Guide to the Principles and Practice of Western Herbal Medicine. London, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2004.

- Hoffmann D. Medical Herbalism: The Science and Practice of Herbal Medicine. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press; 2003.

- Fisher C. Materia Medica of Western Herbs. London, UK: Aeon Books; 2018.

- Rüngeler P, Castro V, Mora G, et al. Inhibition of transcription factor NF-κB by sesquiterpene lactones: a proposed molecular mechanism of action. Bioorg Med Chem. 1999;7(11):2343-2352. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0968-0896(99)00195-9

- Vollmar A, Schäfer W, Wagner H. Immunologically active polysaccharides of Eupatorium cannabinum and Eupatorium perfoliatum. Phytochemistry. 1986;25(2):377-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9422(00)85484-9

- Bartram T. Bartram’s Encyclopedia of Herbal Medicine. London, UK: Robinson; 2013.

- Hensel A, Maas M, Sendker J, et al. Eupatorium perfoliatum L.: phytochemistry, traditional use and current applications. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;138(3):641-651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2011.10.002

- Thomsen M, Gennat H, eds. Phytotherapy Desk Reference. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics; 2000.

- Sarkar A, Roy A, Ghorai T, et al. Eupatorium perfoliatum counteracts TNF-α mediated pathogenesis in chikungunya virus infection. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2025;1-24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-025-05472-1

- Maas M, Deters AM, Hensel A. Anti-inflammatory activity of Eupatorium perfoliatum L. extracts, eupafolin, and dimeric guaianolide via iNOS inhibitory activity and modulation of inflammation-related cytokines and chemokines. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;137(1):371-381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2011.05.040

- Derksen A, Kühn J, Hafezi W, Sendker J, Ehrhardt C, Ludwig S, Hensel A. Antiviral activity of hydroalcoholic extract from Eupatorium perfoliatum L. against the attachment of influenza A virus. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;188:144-152. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2016.04.048

- Missouri Botanical Garden. Eupatorium perfoliatum. Accessed [January 20th 2026].

https://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/PlantFinder/PlantFinderDetails.aspx?taxonid=277187 - Henriette’s Herbal Homepage. Eupatorium perfoliatum – Boneset. Accessed [January 20th 2026].

https://www.henriettes-herb.com/eclectic/king1854/eupatorium-perf.html - Maas M, Petereit F, Hensel A. Caffeic acid derivatives from Eupatorium perfoliatum L. Molecules. 2008;14(1):36-45. doi:10.3390/molecules14010036.

- Colegate SM, Upton R, Gardner DR, Panter KE, Betz JM. Potentially toxic pyrrolizidine alkaloids in Eupatorium perfoliatum and three related species: implications for herbal use as boneset. Phytochem Anal. 2018;29(6):613-626. https://doi.org/10.1002/pca.2775

- Fu PP, Xia Q, Lin G, Chou MW. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids—genotoxicity, metabolism enzymes, metabolic activation, and mechanisms. Drug Metab Rev. 2004;36(1):1-55. https://doi.org/10.1081/dmr-120028426

- International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Eupatorium perfoliatum. Accessed [January 24th 2026].

https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/64311538/67729486 - NatureServe Explorer. Eupatorium perfoliatum. Accessed [January 24th 2026].

https://explorer.natureserve.org/Taxon/ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.143537/Eupatorium_perfoliatum - TRAFFIC. Search results for Eupatorium perfoliatum. Accessed [January 24th 2026].

https://www.traffic.org/search/?q=eupatoriumperfoliatum - Species+. Accessed [January 24th 2026].

https://www.speciesplus.net/