-

How does it feel?

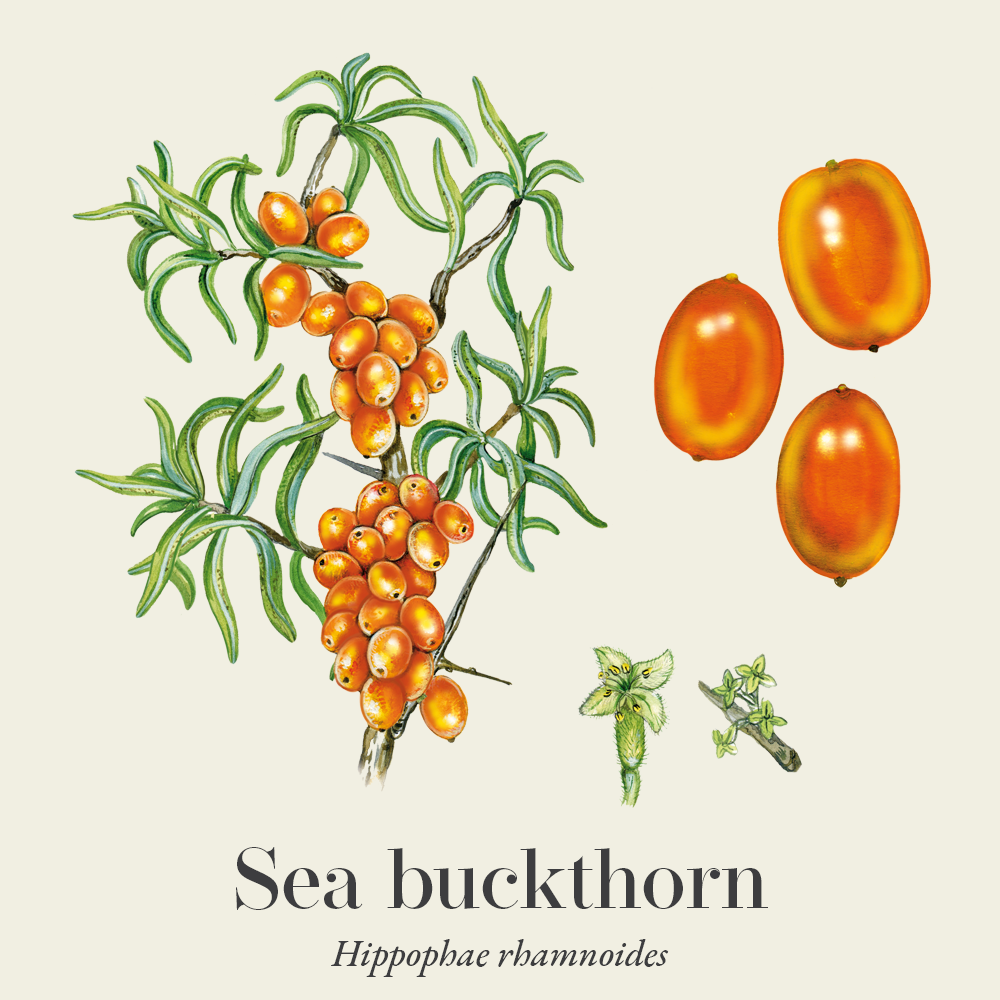

The bright orange berries are arranged in generous clusters but while they are attractive to look at, and stay well into winter on the branches, the taste has not encouraged widespread use in Britain in the past. Upon tasting the berries fresh from the bush or tree, their oily nature slightly masks the bitterness, which then lingers and is also evident in the juice. The dried berry powder is a bright yellowy orange and smells sweet, with a deceptive hint of demerara sugar. However, a little placed on the tongue feels slightly fizzy, while the taste reminds one of an acidic sherbet.

-

What can I use it for?

Sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides) Sea buckthorn berries can be juiced or pulped to give a tart but delicious juice rich in vitamins. An oil rich in omegas 3,6, 7 and 9 fatty acids can also be made by cold pressing the seeds or pulp. These constituents, in addition to the flavonoids, make sea buckthorn particularly useful as a support against infections. Sea buckthorn partners well with rosehips (Rosa canina) in autumn (1). The mixed powders are available to make tea or add to baking, muesli or smoothies. A tea made from sea buckthorn berries is rarely prescribed, however, due to the flavour profile (2). Over the past few years the berries have attracted a reputation as a nutritive superfood, being valued for their antioxidant effects and offering tonic support against the effects of menopause and ageing, including vaginal dryness and dry eyes (3).

Sea buckthorn can be given as a long-term support for blood vessel walls and is antiaggregant and, therefore, offers protection against atherosclerosis (1). The herb has been used as an anti-inflammatory in gastrointestinal ulcers and for treating coughs by loosening and expectorating phlegm. The freshly pressed juice of the fruit is recommended as a treatment for colds, fevers and exhaustion due to the high content of vitamins which includes B1, B2, E and K, in addition to vitamin C (4).

The leaves are healing in wound applications, being rich in phenols and flavonoids, quercetin and kaempferol (5). They also encourage regeneration of mucous membrane tissue by promoting collagen synthesis and keratinocyte proliferation (4).

-

Traditional uses

Sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides) There is no apparent traditional use of sea buckthorn in Britain, which is surprising as the berries have so much to offer both as a food and a medicine. It is most certainly a native plant with pollen records going back to the interglacial periods (6). In the 1824 Universal Herbal, Green refers to the berries being eaten by the Tartars and fishermen of the Gulf of Bothnia making a rob from them (7). This does not seem to have stimulated anyone to copy this idea in England, however. Perhaps the apparent reluctance of birds to strip the branches of the bright berries gave the idea that they were poisonous and this belief persisted in many places (8).

It is even more surprising not to see medicinal use in old herbals. Often, the use of herbs follows through from Dioscorides’ De Materia Medica and sea buckthorn can be found as Ippophaes with a very unlikely illustration in Dioscorides. In this text, the liquor from the root is described as purging choleric or watery matter and phlegm, downwards. A ‘dragm’ is recommended for purgations. There is no mention of using the berries and instead there is only mention of the flowers as those of grapes are described (9).

Widespread traditional use has, however, been recorded in the Himalayas. Sea buckthorn has also been used medicinally in Russia, China, India and Tibet for centuries. This traditional use has sparked eemodern interest and research resulting in a newfound enthusiasm in Western herbal medicine. Traditional use in Tibet goes back to the eighth century. The oily nature of the pulped berries was recognised as useful in treating sluggish, congested states with poor circulation and digestion, leading to low spirits. The sharp heat allocated to sea buckthorn berries is in the Tibetan humoral medicinal classification of “Tarbu”, loosening phlegm and giving it an expectorant action (10).

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

Western energetics

-

What practitioners say

Cardiovascular system

Cardiovascular systemSea buckthorn is recorded as an antiaggregant and cardiotonic indicated for cardiopathy(11.) Formulations based on sea buckthorn have been developed for use in treating coronary heart disease as well as for support after a heart attack or stroke. It is suggested for improving blood circulation and restoring cardiac function (12). A significant cardiac benefit may come from the antioxidant properties of sea buckthorn which, when taken regularly over time, may act by inhibiting the formation of atherosclerotic plaques (1,13).

Digestive system

Sea buckthorn has been used in trials successfully for conventional treatments of gastric ulcers by controlling inflammation and preventing injury to the gastric wall. The antioxidant and anti-inflammatory action activity is important in treating gastric ulcers, and coupled with its antibacterial action can be applied to treat H. pylori (12).

Reproductive system

Sea buckthorn has been used traditionally in supporting uterine health and has a reputation for easing vaginal dryness by supporting mucous membrane tone as a result of the high levels of omega-7 fatty acids (palmitoleic acid), along with omega-6, omega-9 fatty acids, carotenoids, and tocopherols (vitamin E). . Research is ongoing but largely in vitro at present (3).

Skin health

Sea buckthorn is indicated for treating dermatosis, ulcers, sunburn, wounds and infected skin (11). Experiments and clinical trials support use in wound healing. The oil is widely used in treating burns, scalds, ulcerated and infected skin. The seed oil works by decreasing inflammation, increasing circulation, increasing tissue regeneration and improving immunity. The oils are helpful against skin ageing as they promote skin elasticity and hydration (12).

Eye health

Sea buckthorn is classed as ophthalmic and the herb oil is one of the more popular supports when taken as a supplement in capsule form for dry eyes (11). The oil may also contribute to supporting the microcirculation in the eyes(1). Vitamins A and E present in sea buckthorn also help to support eyesight and vision (5).

-

Research

Sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides) There has been considerable research with many studies on sea buckthorn in recent years. The effectiveness of sea buckthorn in cancer therapy has been established in animals, but detailed clinical studies are needed to validate the effects and mechanism of action in human beings living with cancer (12).

Radioprotective properties of Hippophae rhamnoides

An in vivo controlled study using eight-week-old male mice was undertaken to investigate the possible protective effects of sea buckthorn berries against high dose radiation causing acute intestinal injury in mice. One group of mice was subjected to total body X-ray irradiation while the control group was not. Each of these groups was again divided into three to enable testing comparison of a 10 mg/g/day dose of sea buckthorn pulp oil, seed oil, or control olive oil.

The third group were treated with saline for seven days before radiation. Survival time with the olive oil group was 4.5 days. With the seed oil and pulp oil groups it was 8 and 10 days, respectively. Early death in the saline group was mainly from severe intestinal oedema and necrosis.

Intestinal tissues were harvested 72 hours after radiation and prepared for complex testing. Although pretreatment with sea buckthorn oil did not prevent mouse death from high-dose radiation, both the pulp oil and seed oil prolonged the survival time of the mice and reduced their weight loss. While not relieving the reduction of erythrocytes, leukocytes and platelets, the pretreatment of sea buckthorn oil did attenuate the radiation-induced acute intestinal injuries.

It was concluded that the increase in survival time was due to a reduction in acute intestinal injuries and acute inflammation. Two unsaturated fatty acids, PLA and ALA, might be the potential radiation countermeasure candidates for clinical radiation-associated intestinal injury management and further research into intestinal radiation protection is warranted. This study shows promise for sea buckthorn oil protecting from the effects of radiation, and clinical trials on human subjects would be beneficial to further explore its potential (14).

Effect of sea buckthorn on liver fibrosis: A clinical study

A clinical study on the effects of sea buckthorn on liver cirrhosis was carried out with 50 patients aged between 20 and 50. They had varying causes of cirrhosis and elevated levels of at least two of the following — serum collagen types III and IV, laminin or hyaluronic acid. They were randomly divided into two groups. The first group was given 15 g of sea buckthorn in the form of tablets three times a day for six months. The second group received vitamin-B complex.

The benefits of the vitamin A precursor beta-carotene and unsaturated fatty acids in the sea buckthorn produced significant results with remarkable changes in the AST and ALT after treatment. The rate of normalization in the sea buckthorn group was 80%. In the control group it was 56%. Serum laminin, serum collagen types III and IV, and hyaluronic acid and total bile acid were decreased in the sea buckthorn group when compared with the control patients. This indicates sea buckthorn may restrain the synthesis of collagen and other components of the extracellular matrix. The sea buckthorn shortened the time for normalisation of aminotransferases.

The conclusion was that sea buckthorn may be a hopeful drug for prevention and treatment of liver cirrhosis caused by chronic hepatitis B, alcohol consumption or metabolic disorders. More clinical trials are indicated (15).

Sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides) Effect of seabuckthorn seed oil in reducing cardiovascular risk factors: A longitudinal controlled trial on hypertensive subjects

A randomised, controlled, double blind study on the effects of daily supplementation of sea buckthorn seed oil for 32 normal and 74 hypertensive and hypercholesterolemic human subjects sought to establish whether this could affect cardiovascular risk factors. These factors were identified as hypertension and high cholesterol. Supplementation was given at a dose of 0.75 ml sea buckthorn seed oil or sunflower oil over a period of 30 days.

It was found that cholesterol and triglyceride levels were reduced in those subjects where cholesterol was high and hypertension was also reduced. For normal subjects, there was a less pronounced result, but for both the circulatory antioxidant status was improved. These successful results were attributed to fatty acids in the oil and the presence of beta carotene and vitamin E (16).

Effects of dietary supplementation with sea buckthorn (Hippophaë rhamnoides) seed and pulp oils on atopic dermatitis

The effects of supplementation of oil from the seed and pulped fruits of sea buckthorn were researched in a double-blind, placebo-controlled study on atopic dermatitis. Fourty-nine patients were enrolled in the study which took place over a period of four months. Patients were given either seed oil, pulp oil or paraffin oil daily. After one month of taking the pulp oil supplement, there was a slight improvement in symptoms correlated with an increase in proportions of alpha-linolenic acid in plasma phospholipids. There was also slight improvement in the dermatitis of those taking paraffin oil. Those in the seed oil group had no significant improvement (17).

-

Did you know?

Genghis Khan is reputed to have been so successful in his campaigns because his men fed their Mongolian horses sea buckthorn. A veterinary product has now been developed from the herb (18).

Additional information

-

Botanical description

Sea buckthorn is often found on the coast as a thorny shrub and grows to between 1–10 m high. Since it has the ability to spread by suckers, it has been planted in some areas to support sand dunes or prevent soil from erosion. The leaves are narrow, resembling willow but with silvery scales on the under surface when young.

The greenish flowers are tiny and difficult to see, appearing on the previous year’s growth. Male flowers have a shorter tube and larger sepals than the female and they are borne on separate trees. One male tree is sufficient to pollinate 4–6 females, which then produce the bright orange berries. These cluster closely together around the branches and will remain in situ throughout the winter months (1,18).

-

Common names

- Sea buckthorn

- Seaberry

- Sandthorn

-

Safety

Toxicological studies indicate that sea buckthorn oil and extracts are generally safe, showing no acute, chronic, teratogenic, or genotoxic effects in animal models. Human studies report only minor issues such as mild gastrointestinal symptoms and temporary skin discoloration (20).

-

Interactions

There is a potential for sea buckthorn to increase the risk of bleeding when taken in conjunction with antiplatelet medication (21). Theoretically, it could also increase the risk of hypotension when taken with antihypertensive medication. It is advised to consult a medical herbalist in these instances (21,22).

-

Contraindications

Hazards and side effects for therapeutic dosages have not been found (11). There are no known contraindications to sea buckthorn seed oil (14). Human safety data has not been established in pregnancy.

-

Preparations

- Infusion of leaf

- Compress

- Juice

- Puree or preserve

- Oil from pulped berries

- Seed oil

- Powder

-

Dosage

- Infusion of leaves: Two teaspoons chopped leaf per cup

- Pulp or puree: 5–45 g per day

- Juice: Up to 300 ml a day (21)

- Capsules: Seed or pulp oil, or in combination. Take as directed on the packaging information leaflet as this can vary between suppliers.

- Compress: Apply a cloth which has been soaked in the infusion and wrung out.

-

Plant parts used

- Berries

- Seed

- Leaf

-

Constituents

Sea buckthorn leaf constituents

- Phenolic acids: Gallic acid, caffeic acid, ferulic acid

- Flavonoids: Quercetin, kaempferol, rutin, isorhamnetin

- Vitamins A, C, E, riboflavin, Folic acid and K.

- Lycopene and beta carotene

- Organic acids

- Tannins

- Minerals: Potassium, magnesium, calcium iron (23)

Sea buckthorn berries constituents

- Fatty acids: Palmitoleic acid (omega-7), linoleic acid (omega-6), oleic acid (omega-9), palmitic acid, stearic acid

- Vitamins: B1, B2, C,E,K and C

- Proteins

- Carotenoids: Beta-carotene (precursor of Vitamin A), lycopene, lutein, zeaxanthin

- Flavonoids: Rutin, quercetin, myricetin, kaempferol, isorhamnetin

- Tocopherols

- Polysaccharides: Pectin, hemicellulose, cellulose, lignin (24)

Sea buckthorn seeds constituents

- Proanthocyanidins

- Proteins

- Phytosterols

- Tocopherols

- Fatty acids: Alpha-linoleic acid (omega-3), linoleic acid, oleic acid, palmitic acid, stearic acid (5,12)

Constituent levels can vary with different species and habitats.

-

Habitat

Sea buckthorn is as the name suggests, often, though not exclusively, a waterside shrub or tree. Abundant on some coastlines, it is also found near rivers growing in gravel or on sandy banks. Sea buckthorn varieties are native in the Himalayan regions of India, Nepal, Bhutan, Pakistan and Afghanistan, China, Mongolia, Russia and Kazakhstan. Other varieties grow over a wide area of northern Europe from Sweden and Norway to France and Britain. The breadth of distribution results in habitat-related variations in the berries and other plant parts (1,12).

-

Sustainability

Not currently on risk lists but complete data may be missing on the status of the species. Read more in our sustainability guide. Sea buckthorn is listed as of least concern by IUCN redlist (25).

It is not recorded on the NatureServer site (26).

TRAFFIC has just one mention of sea buckthorn at a meeting of SECURE Himalayas stakeholders in 2019. There was a request to simplify rules and regulations for collection and trade of sea buckthorn whose pulp, seeds and oil are traded across the country. It was suggested this would encourage local communities to engage in sustainability issues. There was no suggestion of present danger from current trade (27).

In Britain there has been considerable new planting in East Anglia, as trade expands. These are varieties imported from eastern European countries, however, as research has focussed on those. The wildlife trusts classify the conservation status of sea buckthorn as ‘common’ (28)

Habitat loss and over-harvesting from the wild are two of the biggest threats faced by medicinal plant species. There are an increasing number of well-known herbal medicines at risk of extinction. We must, therefore, ensure that we source our medicines with sustainability in mind.

The herb supplement industry is growing at a rapid rate and until recent years a vast majority of medicinal plant produce in global trade was of unknown origin. There are some very real and urgent issues surrounding sustainability in the herb industry. These include environmental factors that affect the medicinal viability of herbs, the safety of the habitats that they are taken from, as well as the welfare of workers in the trade.

The botanical supply chain efforts for improved visibility (transparency and traceability) into verifiably sustainable production sites around the world is now certificated through the emergence of credible international voluntary sustainability standards (VSS).

Read our article on Herbal quality & safety: What to know before you buy and Sustainable sourcing of herbs to learn more about what to look for and questions to ask suppliers about sustainability.

-

Quality control

Herbal medicines are often very safe to take; however, their safety and efficacy can be jeopardised by quality issues. So, it is important to buy herbal medicines from a reputable supplier, from sources known to test their herbs to ensure there is no contamination, adulteration or substitution with incorrect plant matter, as well as ensuring that recognised marker compounds are at appropriate levels in the herbs.

Some important quality assurances to look for are certified organic labelling, the correct scientific/botanical name, and the availability of information from the supplier about ingredient origins. A supplier should be able to tell you where the herbs have come from, what contaminants are not in the herb, and what the primary compounds are.

-

How to grow

Young bare-rooted bushes are freely available to buy and can be planted in spring or autumn. Sea buckthorn prefers a sunny position and can spread easily through its runners. It is well suited to surviving drought as the roots are capable of spreading a long way in search of water, but observation has been that native situations show proximity to water is preferred (18).

It is recommended to plant sea buckthorn away from any houses. Established bushes can be layered in autumn. If growing from seed, then soaking and scarification will be necessary before sowing in autumn with protection from frost. Male seedlings have prominent axillary buds in spring, which are not found on the females. One male will be needed for pollinating 7–10 females (4).

-

Recipe

Sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides) Rosehip and sea buckthorn fruit cheese*

This is a wonderful winter preserve that can be used as a prophylactic against infection.

Ingredients

- 1 kg cooking apples

- 250 g rose hips

- 1½ tsp sea buckthorn organic powdered fruit

- 450 g sugar

- 450 ml water

How to make sea buckthorn fruit cheese

- Peel and slice the apples into a thick bottomed pan.

- Stir the sea buckthorn powder into the water until dissolved and pour over into the pan.

- Slice the rosehips and place them in a muslin bag.

- Add the rosehip bag to the pan.

- Cook apples until they are soft.

- Remove rosehips.

- Strain the apples through a sieve.

- Return to the pan.

- Cook until they are a thick consistency.

- Pot and seal (19).

*Recipe adapted from Hedgerow Cookery

-

References

- Barker J. The Medicinal Flora of Britain & Northwest Europe : A Field Guide, Including Plants Commonly Cultivated in the Region. Winter Press; 2001.

- Weiss RF, Fintelmann V. Herbal Medicine. Thieme Medical Publishers; 2001.

- Mihal M, Roychoudhury S, Sirotkin AV, Kolesarova A. Sea buckthorn, its bioactive constituents, and mechanism of action: potential application in female reproduction. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2023;14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1244300

- Stobart A. MEDICINAL FOREST GARDEN HANDBOOK : Growing, Harvesting and Using Healing Trees and Shrubs… In a Temperate Climate. Permanent Publications; 2020.

- Ghabru A. Ghabru A. Evaluation of Seabuckthorn Byproducts for in Vivo in Vitro Activities. Lambert Academic Publishing; 2019.

- Godwin H. The History of the British Flora : A Factual Basis for Phytogeography. Cambridge University Press; 2010.

- Green T. The Universal Herbal, Or, Botanical, Medical, and Agricultural Dictionary. Caxton; 1820.

- Chiej R. The Macdonald Encyclopedia of Medicinal Plants. Macdonald Orbus; 1984.

- Gunther R. Dioscorides Greek Herbal. Hafner; 1968.

- Pa-Saṅs-Yon-TanSRP, Yon-Tan-Rgya-Mtsho. Dictionary of Tibetan Materia Medica. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers; 1998.

- Duke JA. Handbook of Medicinal Herbs. CRC Press; 2002.

- Xu D, Yuan L, Meng F, et al. Research progress on antitumor effects of sea buckthorn, a traditional Chinese medicine homologous to food and medicine. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2024;11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1430768

- Chen Y, He W, Cao H, et al. Research progress of sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) in prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2024;11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2024.1477636

- Sureshbabu A, Kumar Barik T, Namita I, Kumar IP. Radioprotective properties of Hippophae rhamnoides (sea buckthorn) extract in vitro. International Journal of Health Sciences. 2008;2(2):45. Accessed October 24, 2025. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3068731/

- Gao ZL. Effect of Sea buckthorn on liver fibrosis: A clinical study. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2003;9(7):1615.https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v9.i7.1615

- Vashishtha V, Barhwal K, Kumar A, Kumar Hota S, Chaurasia OP, Kumar B. Effect of seabuckthorn seed oil in reducing cardiovascular risk factors: A longitudinal controlled trial on hypertensive subjects. Clinical Nutrition. 2017;36(5):1231-1238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2016.07.013

- Yang B. Effects of dietary supplementation with sea buckthorn (Hippophaë rhamnoides) seed and pulp oils on atopic dermatitis. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 1999;10(11):622-630. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0955-2863(99)00049-2

- Stapley C. The Tree Dispensary. Aeon Books; 2021.

- Richardson R. Hedgerow Cookery. Penguin; 1980.

- Dong W, Tang Y, Qiao J, Dong Z, Cheng J. Sea buckthorn bioactive metabolites and their pharmacological potential in digestive diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2025;16:1637676. Published 2025 Sep 23. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2025.1637676

- Natural Medicines Database. Sea buckthorn. Therapeuticresearch.com. Published 2025. Accessed October 25, 2025. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/Data/ProMonographs/Sea-Buckthorn#drug-interactions

- Preedy VR, Ross R, Patel VB. Nuts and Seeds in Health and Disease Prevention. Elsevier; 2011

- Bośko P, Biel W, Witkowicz R, Piątkowska E. Chemical Composition and Nutritive Value of Sea Buckthorn Leaves. Molecules. 2024;29(15):3550. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29153550

- Drugs.com. Sea Buckthorn Uses, Benefits & Dosage. Drugs.com. Published 2024. Accessed October 24, 2025. https://www.drugs.com/npp/sea-buckthorn.html

- Wilson B, Chadburn H. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Hippophae rhamnoides. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Published October 3, 2017. Accessed October 25, 2025. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/55686342/119996497

- NatureServe. Search | NatureServe. Natureserve.org. Published 2025. Accessed October 25, 2025. https://www.natureserve.org/search/node?keys=sea+buckthorn

- Traffic. High flying: securing livelihoods and biodiversity in India’s Himalayas – Wildlife Trade News from TRAFFIC. Traffic.org. Published 2019. Accessed October 25, 2025. https://www.traffic.org/news/high-flying-securing-livelihoods-and-biodiversity-in-indias-himalayas/

- Wildlife Trust. Sea-buckthorn | Surrey Wildlife Trust. Surreywildlifetrust.org. Published 2025. Accessed October 25, 2025. https://www.surreywildlifetrust.org/wildlife-explorer/trees-and-shrubs/sea-buckthorn?gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=20312350455&gbraid=0AAAAADQCUKvnoanK85S6chvbRtwFWKxSJ&gclid=CjwKCAjw6vHHBhBwEiwAq4zvAx8R6wW8jdjQ599xKCsYvbz7DJJF6SPWwixAC3sKsd1IOGomCk6ZEBoCgEsQAvD_BwE