-

How does it feel?

Nowadays, only the essential oil from distillation of the leaves of wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens, G. fragrantissima) is recommended for use, and solely externally at a maximum dilution of 2.4%, due to the high toxicity risk of ingesting methyl salicylate (1–3).

The leaves may be described as aromatic, astringent, and pungent; whereas the berries, though they share the astringency of the leaves, instead have a sharp and sour quality.

Wintergreen has a unique, powerful aroma, combining its strong, medicinal scent with fruity and woody notes. Whilst the aroma is potent and stimulating on inhalation, when applied topically it has a cooling, soothing and pain-relieving effect. This quality makes wintergreen of particular help for treating sore muscles and joints (4,5,7).

-

What can I use it for?

In modern Western herbal medicine, wintergreen is used externally only, primarily to treat both musculoskeletal and neurological pain and inflammation, and in traditional energetic terms, to clear heat (4).

As well as via the skin during topical use, some of the volatile (essential) oil is absorbed via the olfactory system (the sensory system that governs our sense of smell) when used diluted in a massage oil blend; however, wintergreen is not suitable for diffusing or as a steam inhalation (4).

-

Into the heart of wintergreen

Wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens) Limited information is available on this plant’s psychospiritual use, and it is not widely documented with many energetic uses in herbalism or aromatherapy. However, Holmes notes its ability, in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) terms, to clear heat – and describes its qualities as cooling, sweet, woody, and pungent (4). This corresponds well to its anti-inflammatory and analgesic actions. Wintergreen is associated with the wood and water elements in TCM, and has a descending, stabilising character (4).

Tierra, however, notes wintergreen leaves as having a warming, spicy, and energetic character with an affinity for the liver and lungs; likely due to its expectorant and decongestant actions (9). Contrary to most modern advice, Tierra recommends internal use to “relieve pain and rheumatic complaints”. This is no longer recommended by herbalists due to toxicity concerns regarding methyl salicylate, the plant’s primary chemical constituent (3,9).

Wintergreen’s psychospiritual energetic qualities and uses include ‘warming up’ and invigorating the sense of self, strengthening confidence and resolve. It is indicated for those who have lost their will, power, and passion, since it dispels fear and paranoia — it can incite one’s motivation to overcome challenges (4).

-

Traditional uses

Traditionally, Native American communities have used both the berry and leaf internally, eating the fresh berries as a food, or brewing an infusion of the leaves to treat rheumatic conditions, headaches, fevers and sore throats (10).

Wintergreen was also used commonly in gargles, mouthwashes and poultices due to its antiseptic properties, and to this day is still used in sports injury lotions and gels, and some dental care products (6).

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

Western actions

Ayurvedic actions

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

Western energetics

Chinese energetics

-

What practitioners say

Musculoskeletal system

Musculoskeletal systemConditions that benefit from treatment with wintergreen essential oil include “hot” conditions — rheumatoid arthritis (and rheumatic conditions in general), osteoarthritis, myalgia, muscle sprains and sciatica (5,11). It can also be very useful in improving acute inflammatory musculoskeletal issues, such as tendinitis, or tissue trauma accompanied with pain, haematoma, or bruising (4). It is commonly used by herbalists working in first aid settings to treat fractures, sprains or strains by supporting healing and reducing inflammation.

Reproductive and urinary system

Wintergreen’s affinity for both the reproductive system, coupled with its diuretic action, makes it a useful treatment for urogenital inflammation that may be caused by an infection or non-infective agents (4,5).

Cardiovascular system

Whilst widely used by herbalists to treat skeletal muscle complaints, wintergreen’s anti-inflammatory and antispasmodic actions also affect smooth muscle tissue, such as blood vessel walls and cardiac (heart) muscle. Its hypotensive and vasodilatory effects add to this, making wintergreen a useful treatment for conditions like angina pectoris, headaches and migraines (4,12).

-

Research

Wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens) Whilst few clinical trials investigating the impact of wintergreen oil exist, in vitro and ex vivo work is more extensive and has explored the efficacy of synthetic and natural standardised extracts of methyl salicylate, wintergreen’s primary constituent.

Safety and efficacy of compound methyl salicylate liniment for topical pain: A multicenter real-world study in China

A randomised, double-blind, parallel controlled multicentre in vivo clinical trial was conducted in China to evaluate the efficacy and safety of compound methyl salicylate liniment in the treatment of acute and chronic soft tissue pain. A positive control drug, diclofenac sodium liniment, was used, and the compound contained methyl salicylate (as well as menthol, camphor, chlorpheniramine maleate, and thymol).

Of the individuals with acute or chronic tissue pain that were recruited, 3515 participated in the trial. Patients applied the methyl salicylate liniment to the affected area three times a day for seven days. Patients reported pain and tenderness levels before and after treatment. After seven days of treatment, excluding subjects who used analgesics or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), the pain relief rate was 78.75%.

At baseline, patients’ average self-reported pain score was initially 5.3/10. When pain was measured again seven days after treatment with the liniment, pain scores dropped to around 2.8 on average, showing a statistically significant (p < 0.0001) reduction in pain.

The authors concluded that their formula was “safe and effective” and could “relieve… shoulder and neck pain, back pain, or muscle pain”, with no new adverse drug reactions identified (13).

The effect of standardised leaf extracts of Gaultheria procumbens on multiple oxidants, inflammation-related enzymes, and pro-oxidant and pro-inflammatory functions of human neutrophils

An ex vivo study aimed to understand the ideal solvent for extracting the active chemical constituents of wintergreen, as well as understanding its biological effects in human neutrophils (immune cells).

A standardised methanol–water extract was used, containing polyphenols, salicylates, catechins, procyanidins, phenolic acids and flavonoids. The extract showed a significant dose-dependent ability to downregulate pro-oxidant and pro-inflammatory activity of human neutrophils (immune cells). It strongly reduced reactive oxygen species (ROS), that can damage human cells and DNA in high amounts. It downregulated the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and enzymes that remodel tissues, and also scavenged oxidants and inhibited pro-inflammatory enzymes. This means reduced inflammation, reduced tissue damage, and improved healing (14.)

Salicylate‐containing rubefacients for acute and chronic musculoskeletal pain in adults

A Cochrane systematic review of 1,368 patients found that whilst most topical salicylates were well tolerated short term by patients experiencing both acute and chronic pain, the review was limited in terms of efficacy and safety by insufficient data of adequate quality. Issues included inconsistent outcome reporting, high risk of study bias and a lack of heterogeneity in study design, as well as relatively small participant numbers. A lack of rigorous safety and adverse event reporting contributed to the limitations (15).

Phytochemistry and biological profile of Gaultheria procumbens L. and wintergreen essential oil: From traditional application to molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets

A review of over 150 studies on wintergreen identified anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and photoprotective potential of a range of extracts which were taken from various parts of the plant. Wintergreen essential oil was found to have antifungal, larvicidal, antibacterial and insecticidal activity. However, most studies covered in vitro and ex vivo non-cellular (and cell-based) tests, so more research is needed on external use in vivo to further investigate wintergreen’s therapeutic potential and efficacy (16).

-

Did you know?

Wintergreen essential oil is distilled from the leaves of the plant and contains up to 99.5% methyl salicylate, a chemical constituent responsible for the herb’s analgesic properties, yet the dried leaves only contain 1.48%, and the fresh leaves even less at 0.59%, (3,7,17). Methyl salicylate can also be found in the Betula (birch) family.

Methyl salicylate is converted to salicylic acid through hydrolysis after ingestion or through skin absorption (18).

Wintergreen constitutes one of the primary ingredients in Tiger balm, giving its distinctive aroma and effect (19).

Additional information

-

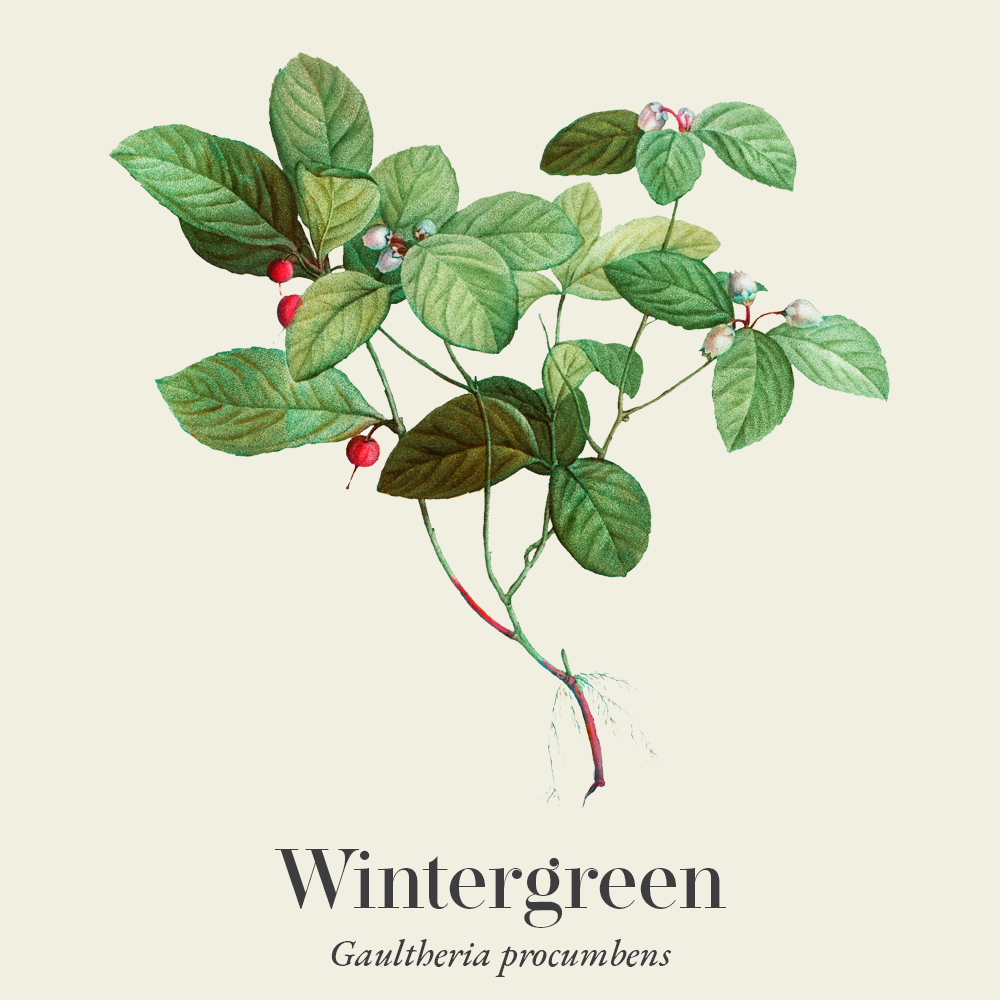

Botanical description

An ericaceous, evergreen shrub in the heath (blueberry) family. Wintergreen will grow up to 15 cm in height and spreads as it grows, and has round, leathery leaves. Its leaves are spicy and aromatic, turning red in winter. It produces small, white bell-like flowers and red berries, which is how the plant adopted the name ‘Canada teaberry’. It prefers acidic (ericaceous) soils (1,22).

-

Common names

- Checkerberry

- Eastern teaberry

- Canada teaberry

- Gaultheria

- Gaulthérie

- Sempreverdi

- Gaulteria

-

Safety

The essential oil of wintergreen should only be used short term — up to a maximum of two weeks, for the management of acute conditions (or flare-ups of chronic conditions) (6,20).

Wintergreen should not be used during pregnancy, breastfeeding, children under seven or early infancy — high doses of the herb are teratogenic (can cause developmental abnormalities). It should be avoided in conjunction with anticoagulants (e.g., aspirin, warfarin), as it can enhance their activity (4,14).

It should be avoided by those with blood clotting disorders or undergoing major surgery due to haemorrhage risk. It should also be avoided in patients with salicylate allergies or intolerance — this often includes people with ADD/ADHD (6,14).

One teaspoon of wintergreen essential oil is equivalent to around 21 adult aspirin tablets, and 4 ml of oil can be lethal to a child, whilst 6 ml could be lethal to an adult if consumed (4,21).

Topical application of the oil diluted within a sensible base (such as a balm or base oil) at an appropriate dilution rarely causes issues but those with sensitive skin may provoke reactive eczema or urticaria (3–5).

-

Interactions

Since methyl salicylate can potentiate (increase the effect of) anticoagulant drugs, such as aspirin or warfarin, it should be avoided completely alongside these medications, as it could provoke haemorrhage — even if the wintergreen oil is applied externally. Several case reports have confirmed this (3,4,21).

-

Contraindications

This herb should be avoided completely in pregnancy, while breastfeeding and in early infancy. It should not be used alongside anticoagulant medication or with suspected or confirmed salicylate allergy or intolerance. It should be avoided if undergoing major surgery and with blood clotting disorders (3,5,12).

-

Preparations

Essential oil, diluted in a suitable medium:

- Balm (2.4% maximum) (14)

- Liniment (1-2% dilution of essential oil in a base oil) (6)

- Massage oil (1% dilution in base oil) (6)

- Fluid extract

- Infusion or decoction of dried or fresh leaves

-

Dosage

- Fluid extract (1:1 | 25%): 0.5-1ml (4)

- Infusion/decoction (of dried herb): 0.5-1g daily (4)

- Other preparations: Essential oil is distilled from the leaves and used at a maximum dermal application of 2.4%, diluted in a suitable base oil or other medium (3,5,12).

-

Plant parts used

- Leaf (mainly steam-distilled essential oil but also sold as fluid extracts or dried leaf for infusions)

- Berries (traditionally, not in modern preparations)

-

Constituents

- Phenolic compounds: Gaultherin, salicylic, p-hydroxy benzoic, vanillic, caffeic and gentisic acids (5)

- Volatile oil (<1%): Containing mainly methyl salicylate (up to 99.7%). This is present only in the steam distilled essential oil, which is the most commonly-used preparation today. When the oil has been distilled, the glycoside gaultherin hydrolyses (detaches) from the methyl salicylate, releasing it (2,3,5,20).

-

Habitat

Wintergreen is native to north-eastern America and Canada and has been introduced to the UK. It prefers poor, acidic (ericaceous) soils, and will grow in damp soil, in shade (full or partial). It is often found in woodland clearings, particularly underneath conifers (1,22,23).

-

Sustainability

According to the Natureserve database, wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbensis largely ranked ‘Secure’ in status, although it is listed as ‘Vulnerable’ in South Carolina, USA and Manitoba, Canada and is listed as ‘Critically Imperiled’ in Newfoundland Island (24). The causes of the statuses in these three areas is partly attributed to the limit of its natural climate range, but also habitat destruction for agricultural use, slow rhizome-based plant reproduction (often disrupted by forest fires), and climate change (27, 20-31).

It is not listed on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Plants Status, TRAFFIC or Species+ databases as being endangered or widely trafficked (24–26). In the UK, this plant is grown as an ornamental, whilst in the USA and Canada it is wild harvested or cultivated as a medicinal herb by farmers (12,16,29).

-

Quality control

Adulteration of wintergreen essential oil is common; as synthetic methyl salicylate is widely and easily produced, it is often sold as ‘wintergreen oil’. It is recommended to verify the oil’s origin before purchasing it (3,6).

-

How to grow

A low maintenance plant, wintergreen will grow in both damp or drier soils, although it will grow best in a moist, well-drained soil. Its natural habitat is acidic ground, which is partially shaded, so best results will be had if it is planted in similar conditions. It can be propagated via semi-hardwood cuttings, or grown from seed. It has a spreading, suckering growth habit which makes it ideal for ground cover in shaded areas. It is drought tolerant and evergreen, making it a robust and resilient ornamental and medicinal addition to the garden (22,23,28).

-

Recipe

Wintergreen essential oil (Gaultheria procumbens) Anti-inflammatory healing joint balm

This soothing balm is a basic version of one many medical herbalists use in their clinics. It is ideal for cooling hot, inflamed joints, strains and sprains and reducing both pain and swelling.

This recipe makes one 60 g tin of balm and can be scaled up if desired. The below recipe is based on 20 gtt constituting 1 ml of essential oil.

You will need

- 60 ml tin

- Jug

- Saucepan

- Hob

- Wooden spoon

- Small spatula

- Cooking thermometer

Ingredients

- 52 ml sweet almond (Prunus dulcis) base oil, organic. You can use a St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) or marigold (Calendula officinalis) infused base oil if you prefer.

- 8 g beeswax pellets (or if using soy wax, use 12 g, reducing base oil to 48 ml)

- Up to 20 gtt wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens) organic essential oil. Do not exceed this dose.

- 6 gtt lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) organic essential oil

- 3 gtt peppermint (Mentha piperita) organic essential oil

How to make a healing joint balm

- Add your base oil and wax pellets to a heat proof bowl.

- Put a pan ⅓ full with water onto a medium heat.

- Place the bowl into the water, suspended above the base of the pan if possible. A Pyrex jug hooked over the edge of the pan works well.

- Stirring frequently, ensure your wax and oil has melted together before removing the bowl from the heat and turning off the hob.

- When the base mixture has cooled to about 60°C, add your essential oils and stir for about 30 seconds.

- Before the mixture sets, use the spatula to spoon it into the tin, and leave to cool. Do not put it in the fridge, allow it to cool at room temperature.

- Label your balm with the name and date.

- Use up to three times per day on the affected area.

Safety note: Do not ingest the balm nor apply it to broken skin or mucous membranes.

-

References

- Badoux D. Contemporary French Aromatherapy: A Pharmacological and Therapeutic Guide to 100 Essential Oils. Jessica Kingsley; 2019.

- Botanical Research Institute of Texas (BRIT), University of Michigan. Native American Ethnobotany Database. 2003. Accessed July 17, 2025. http://naeb.brit.org/uses/search/?string=Gaultheria+procumbens

- Derry S, Matthews PRL, Wiffen PJ, Moore RA. Salicylate‐containing rubefacients for acute and chronic musculoskeletal pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(11):CD007403. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007403.pub3

- Fisher C. Materia Medica of Western Herbs. Aeon; 2018.

- Guo J, Hu X, Wang J, et al. Safety and efficacy of compound methyl salicylate liniment for topical pain: A multicenter real-world study in China. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1015941. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.1015941

- Holmes P. Aromatica. Vol 2. Singing Dragon; 2019.

- Martin I. Aromatherapy for Massage Practitioners. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

- Michel P, Granica S, Rosińska K, et al. The Effect of Standardised Leaf Extracts of Gaultheria procumbens on Multiple Oxidants, Inflammation-Related Enzymes, and Pro-Oxidant and Pro-Inflammatory Functions of Human Neutrophils. Molecules. 2022;27(10):3357. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27103357

- Michel P, Olszewska MA. Phytochemistry and Biological Profile of Gaultheria procumbens L. and Wintergreen Essential Oil: From Traditional Application to Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(1):565. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25010565

- Oakeley H, ed. Modern Medicines from Plants. CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; 2024.

- Peace Rhind J. Essential Oils: A Comprehensive Handbook for Aromatic Therapy. 3rd ed. Singing Dragon; 2019.

- Royal Horticultural Society (RHS). Gaultheria procumbens checkerberry Shrubs. Royal Horticultural Society (RHS). Accessed July 18, 2025. http://www.rhs.org.uk/plants/7679/gaultheria-procumbens/details

- Society (http://plantfinder.nativeplanttrust.org) NEWF. Gaultheria procumbens. New England Wild Flower Society. Accessed July 18, 2025. https://plantfinder.nativeplanttrust.org/plant/Gaultheria-procumbens

- Tisserand R, Young R. Essential Oil Safety. 2nd ed. Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2014.

- Gaultheria procumbens Checkerberry, Eastern teaberry, Teaberry, Creeping Wintergreen. PFAF Plant Database. Accessed July 18, 2025. https://pfaf.org/user/plant.aspx?LatinName=Gaultheria+procumbens

- Gaultheria procumbens NatureServe Explorer. Accessed July 18, 2025. https://explorer.natureserve.org/Taxon/ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.143319/Gaultheria_procumbens

- Valk AG. Forest Ecology. Springer; 2009.

- Telaprolu KC, Grice JE, Mohammed YH, Roberts MS. Human Skin Drug Metabolism: Relationships between Methyl Salicylate Metabolism and Esterase Activities in IVPT Skin Membranes. Metabolites. 2023;13(8):934-934. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo13080934

- Tiger balm. TIGER BALM | Painkiller for muscle and joint pain. Tigerbalm.ch. Published 2025. Accessed July 23, 2025. https://www.tigerbalm.ch/en/Aetherische-Oele/Methylsalicylat

- International Federation of Aromatherapists. Ingestion and Neat Application of Essential Oils Guidance . Accessed March 10, 2025. https://ifaroma.org/application/files/9215/5169/6992/INGESTION__NEAT_APPLICATION_OF_ESSENTIAL_OILS_GUIDANCE.pdf

- NatMed Pro – Interactions Checker Tool. Accessed July 18, 2025. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/Tools/InteractionChecker

- Species+. Accessed July 18, 2025. https://www.speciesplus.net/species#/taxon_concepts?taxonomy=cites_eu&taxon_concept_query=gaultheria%20procumbens&geo_entities_ids=&geo_entity_scope=cites&page=1

- The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Gaultheria procumbens. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN). Accessed July 18, 2025.https://www.iucnredlist.org/search?query=gaultheria%20procumbens&searchType=species

- The Trade in Wild Species – TRAFFIC – The Wildlife Trade monitoring network. Accessed July 18, 2025. https://www.traffic.org/what-we-do/the-trade-in-wild-species/

- Wintergreen. Herbalgram. Accessed July 18, 2025. https://www.herbalgram.org/resources/healthy-ingredients/wintergreen/

- Gaultheria procumbens L. Plants of the World Online (POWO). 2025. Accessed July 17, 2025. http://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:330655-1

- Ojha PK, Poudel DK, Dangol S, et al. Volatile Constituent Analysis of Wintergreen Essential Oil and Comparison with Synthetic Methyl Salicylate for Authentication. Plants. 2022;11(8):1090. doi:10.3390/plants11081090

- Cuchet A, Jame P, Anchisi A, et al. Authentication of the naturalness of wintergreen (Gaultheria genus) essential oils by gas chromatography, isotope ratio mass spectrometry and radiocarbon assessment. Industrial Crops and Products. 2019;142:111873. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.111873

- Cisternas-Fuentes A, Koski MH. Drivers of strong isolation and small effective population size at a leading range edge of a widespread plant. Heredity. 2023;130(6):347-357. doi:10.1038/s41437-023-00610-z

- Sr TS. American Wintergreen. Our Breathing Planet. May 6, 2022. Accessed July 20, 2025. https://www.ourbreathingplanet.com/american-wintergreen/