-

Herb overview

Safety

Avoid with anticoagulants, antidiabetics and quinolone antibiotics. Avoid also with biliary obstruction or Asteraceae sensitivity.

Sustainability

Low risk/green

FairWild sources availableKey constituents

Inulin

Sesquiterpene lactones

FlavonoidsQuality

Native to eastern Europe

Both cultivated and wild-harvested

Contamination risk from pollutants such as heavy metalsKey actions

Bitter

Hepatic

Laxative

DiureticKey indications

Dyspepsia

Fluid retention

Eczema

ArthritisKey energetics

Cooling

DryPreperation and dosage

Root and leaf

Decoction: Between 2–8 g three times daily

Tincture 1:5 (45%): Between 5–10 ml three times daily

-

How does it feel?

Dandelion is a bitter remedy, although also a gentle one. Upon tasting the leaf, there is an instant bitter taste, settling into an earthy bitter quality, a slight acridity and a subtle sweetness. In the case of the root, the bitterness is effected by a more mucilaginous sweetness, which varies depending on the time of year it is collected — a spring root will have used up more of its carbohydrate (inulin) stores over winter and will be more bitter. Even then, the presence of inulin can linger on the tongue long after the bitterness has faded.

Dandelion’s bitterness is due to sesquiterpene lactones, unique to this plant, but the contribution of the inulin in the root is a reminder that this is above all a gentle bitter, and a good option to begin exploring bitter plants (1).

-

Into the heart of dandelion

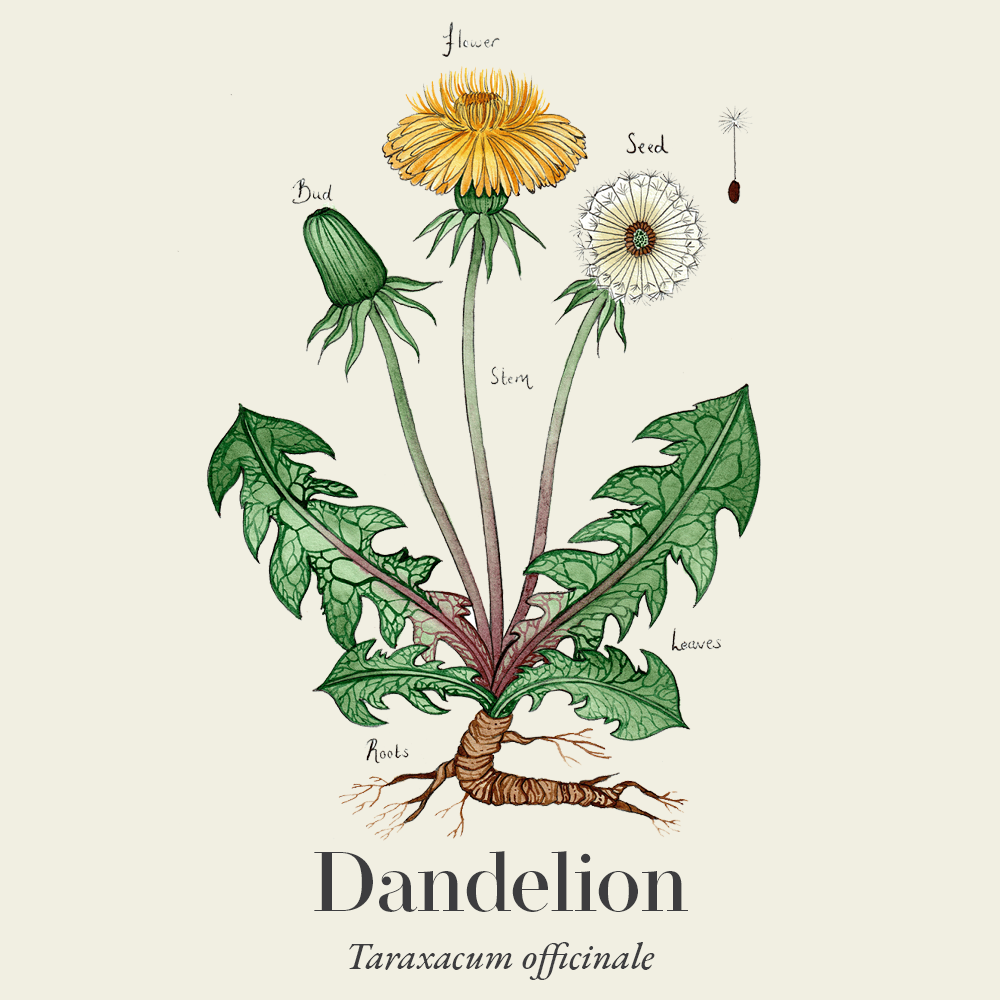

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinalis) Dandelion is one of the cornerstones of herbal treatment in many cultural traditions, certainly seen as such by herbal practitioners in the UK. Modern life can put a significant strain on the liver, as it has to detoxify increasing quantities of ingested industrial pollutants, and for some late 20th century practitioners, dandelion became almost a constant feature in a prescription, as a general detox component.

This reverence of dandelion, however, is not new. The great herbal archivist of the 17th century, John Parkinson, sums up dandelion’s effect in the first line of his description: “by the bitternesse doth more open and clense, and is therefore very effectuall for the obstructions of the liver, gall and spleene, and the diseases that arise from them, as the jaundise and the hypochondriacall passion…”. He moves straight on from extolling these hepatic virtues of dandelion to say:

“it wonderfully openeth the uritorie parts, casing abundance of urine, not onely in children … without restraint or keeping it backe they water their beds, but in those of old age also upon the stopping or yeelding small quantitie of urine; …it also powerfully clenseth apostumes and inward ulcers in the uritorie passages, and by the drying and temperate qualitie doth afterwards heale them“.

It is interesting to note too that various species of dandelion have been used around the world consistently for skin, liver, digestive and urinary problems (3).

-

What practitioners say

In summary, dandelion can be seen as gently improving both liver and kidney functions. Although there is a tendency to use the root for the liver and leaf for the kidney, there is enough overlap to recommend both plant parts. In the case of the liver and digestion it combines well with and overlaps the activity of artichoke leaf (Cynara scolymus) (6).

In summary, dandelion can be seen as gently improving both liver and kidney functions. Although there is a tendency to use the root for the liver and leaf for the kidney, there is enough overlap to recommend both plant parts. In the case of the liver and digestion it combines well with and overlaps the activity of artichoke leaf (Cynara scolymus) (6).Digestive system

As a gentle bitter digestive, dandelion root is a standard first step in exploring this approach, perhaps as a test run for stronger bitters like andrographis (Andrographis paniculata), gentian root (Gentiana lutea), and wormwood (Artemisia absinthium). Bitters were traditionally described around the world as cooling and drying, suggesting they could be suitable in poor appetite linked to fever and inflammatory conditions, where heat or humidity is exacerbatory, and traditionally where there is a yellow coating on the tongue. They are also particularly useful where there is a liver-bile element, marked by intolerance to rich food, fats and alcohol, and in managing more overt problems like jaundice linked to hepatitis, gallbladder conditions and inflammatory gut diseases. Artichoke and chicory (Cichorium intybus) are of comparable strength and are often combined in traditional bitter digestive blends (1).

Skin health

Dandelion’s bitter quality also lends it to being a common ingredient in herbal regimes for managing chronic inflammatory problems around the body, notably skin conditions like eczema. Dandelion supports effective elimination of metabolic waste through the liver and kidneys, which can be a causative factor in chronic skin conditions. Another component can be sluggish bowel movements, for which dandelion is also indicated (1,2,7).

Musculoskeletal system

Dandelion is known to modulate the inflammatory response associated with osteoarthritis and gout through its excretory action on the liver and kidneys. There is a strong naturopathic tradition that some arthritic problems are linked with inadequate elimination of acid wastes produced by cell metabolism. Much of this is expelled as carbon dioxide from the lungs, with the rest removed in the bowel, sweat and urine. The aim in these traditions is to consume higher proportions of foods that leave alkaline residues after digestion (plant foods) and reduce acid-forming (typically animal) foods — in other words, a more vegetarian diet. Dandelion is one of a number of familiar remedies that were seen to improve the elimination of acidic metabolites (e.g., phosphates and urates) by the kidneys, along with common folk remedies celery seed, nettles (Urtica diocia), and birch (Betula pendula) (8,9,10).

Urinary system

With its role in diluting both the bile and urine, thus reducing the propensity for crystal and stone deposition in each, it is indicated in the treatment of kidney stones (10).

All parts of dandelion, especially the leaf, have demonstrated diuretic effects. This has led to dandelion being used in fluid retention, oedema and even to reduce high blood pressure. It can also be used in a mixture to relieve fluid retention premenstrually. It is worth noting that one needs to take relatively high doses to elicit this effect (11).

-

Dandelion research

Dandelion root (Taraxacum officinale) In spite of its widespread use around the world, clinical evidence for the effects of dandelion are minimal, with most of the research being laboratory studies.

The diuretic effect in human subjects of an extract of Taraxacum officinale folium over a single day

In one pilot human study involving 17 subjects, administration of a fresh leaf hydroethanolic dandelion leaf extract at a dose of 8 ml led to a significant increase in the frequency of urination in the five hour period after the first dose. There was also a significant increase in the excretion ratio in the five hour period after the second dose of extract. The third dose failed to change any of the measured parameters (11).

Taraxacum—A review on its phytochemical and pharmacological profile

This review found Taraxacum officinale to be rich in sesquiterpene lactones including taraxinic acid and taraxasterol which are responsible for the bitter taste. These constituents are responsible for its digestive, choleretic and anti-inflammatory effects through their action on inflammatory mediators. The phenolic compounds (hydroxycinnamic acids including caffeic and chlorogenic acids) and flavonoids were shown to exhibit potent antioxidant activity, helping to protect hepatic tissue against damage from free radicals. The triterpenes (taraxasterol) is associated with anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective actions, whilst the inulin rich polysaccharides (higher in the root) offer a prebiotic effect, helping to support microbiome (12).

The role of dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) in liver health and hepatoprotective properties

This narrative review explores dandelion and its effect on the liver. Preclinical evidence from animal models indicates that dandelion extracts can protect against chemically induced liver injury, including damage caused by alcohol, carbon tetrachloride, and paracetamol, as a result of its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory actions. The triterpene taraxasterol is a key constituent, shown to modulate oxidative stress and inflammatory pathways implicated in hepatic injury. While these findings support traditional use, the authors conclude that more robust human clinical trials are needed to establish safety, efficacy, optimal dosing, and potential drug interactions of dandelion (5).

The potential of dandelion in the fight against gastrointestinal diseases: A review

This review evaluates the effect of dandelion in the treatment of gastrointestinal (GI) diseases. It found that preclinical evidence suggests dandelion preparations exert protective effects across a range of conditions—including dyspepsia, gastritis, GERD, ulcerative colitis, liver disorders, gallstones, pancreatitis and GI malignancies—via anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, apoptotic, autophagic and cholinergic mechanisms, as well as potential interactions with the gut microbiota. While these findings support traditional use, the authors conclude that clinical data remain limited, and further studies are needed to further clarify its mechanisms and safety in the treatment of gastrointestinal diseases (13).

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

Western energetics

Chinese energetics

-

What can I use dandelion for?

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) Dandelion leaf and root have been widely used for skin conditions and joint problems. Dandelion is especially effective in cases where there are also underlying liver, bile and urinary factors.The root, particularly, is one of the safest and most efficatious ways to improve biliary elimination (choleresis) and relieve an overworked liver.

It can be used in cases of fat and alcohol intolerance coupled with associated digestive congestion or dyspepsia, and even to relieve the symptoms of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) — sometimes associated with metabolic syndrome and build up of abdominal fat. An increase in bile flow by dandelion can help to relieve stubborn constipation (1,2).

The choleretic effect of dandelion means that it is a standard remedy for gallbladder problems, such as gallstones and cholecystitis. It is certainly a standby gentle remedy if there is a tendency to these problems. It combines well with artichoke leaf (Cynara scolymus) to relieve gallstones; however, care must be exercised to ensure there is no obstruction before using these herbs.

Chronic skin conditions are often associated with poor liver detoxification and in these cases dandelion can be transformative (1,2). Dandelion leaf is more often associated with diuretic properties — it is a frequent component of blends to reduce fluid retention, oedema and to help flush the urinary tract when there are stones and infections. Its application to arthritis (particularly osteoarthritis and gout) relates to ancient associations of these conditions with the build up of metabolic waste in the body. A classic addition in these problems is celery seed (Apium graveolens).

Dandelion is a bitter, the basis of its benefits for the liver, and as such is also a gentle but effective bitter digestive remedy, a component in any blend to improve appetite and digestive function (1,2).

-

Did you know?

Dandelion comes from the French ‘dent de lion’ (lion’s tooth) and refers to the characteristic shape of the leaf. As a result, dandelion is easily recognisable in any sward even without flowers or the seed heads. Its common French name ‘pisenlit’ derives from its diuretic properties and contains the implicit instructions not to take dandelion too close to bedtime!

For most purposes the root should be picked in early spring rather than autumn because of the improved bitterness at that time (due to the plant using up the slightly sweet and starchy inulin during the winter months). The leaves are picked in the spring or early summer preferably before flowering (6).

-

Botanical description

A very well-known plant that is, however, confused with a number of similar plants such as the hawkweeds, hawkbits and cat’s-ears.

The dandelion arises as a rosette of leaves in a variety of shapes, from almost entire lanceolate, to deeply pinnatifid with three to six often backward-pointing triangular lobes likened to lion’s teeth (dent de lion).

From the centre of the rosette arises a single hollow stem, yielding white sap on cutting, and terminating in a yellow capitulate flowerhead made up of 200 or more yellow ligulate bisexual florets each giving way in turn to the familiar floating pappus with seed — it is the globular mass of these pappi that comprise the ‘fairy clock’ so beloved of children.

The long taproot issues from a short rhizome: all the underground parts are covered by a dark-brown bark, but are almost white inside, and like the stem, produce a bitter-tasting white milky sap (17).

-

Common names

- Fairy clock

- Lion’s tooth

- Löwenzahn (Ger)

- Pisenlit (Fr)

- Dente di leone (Ital)

- Diente de león (Sp)

-

Habitat

Dandelion is native to the United Kingdom. It grows in all kinds of grasslands from lawns to roadside verges, and pastures to traditional meadows (18).

-

How to grow dandelion

Dandelions commonly grow in UK gardens, and are very resilient, being able to withstand a variety of growing conditions. They will grow in both sunny and shady environments, and planting in shade will reduce some of the bitter components.

Seeds can be sown anytime from spring through to the autumn and should be spaced around 20 cm apart. Cold stratifying the seeds beforehand will increase the chances of germination. The seeds will require light for germination so press them lightly into the surface of the soil. Water regularly to keep the soil moist and the seeds should germinate within a couple of weeks (17).

-

Herbal preparation of dandelion

- Dried

- Powdered root

- Tincture

- Decoction of the root

-

Plant parts used

- Root

- Leaf

-

Dosage

Dosage dandelion root

- Tincture 1:5 (45%): Between 5–10 ml three times daily

- Decoction: Between 2–8 g three times daily

Dosage dandelion leaf

- Tincture 1:5 (45%): Between 2–8 ml three times daily

- Infusion: Between 4–10 ml three times daily (15)

-

Constituents

There are some differences between the constituents of root and leaf though much overlap

- Sesquiterpene lactones: Taraxacin, mongolicumin B, and taraxinic acid derivatives

- Triterpenoids: Taraxasterol, campesterol, cycloartenol and taraxerol

- Phenolics: Chlorogenic, chicoric, and caffeoyltartaric acids, coumarins (aesculin and cichoriin), lignans (eg mongolicumin A) and taraxacosides.

- Serine proteinase: Taraxalisin present in the fresh latex (particularly in spring).

- Taraxinic acid 1′-O-beta-D-glucopyranoside (an allergen)

- Inulin (in the root)

- Flavonoids: Quercetin glycosides and luteolin in the leaf

- Carotenoids: Lutein, violaxanthin, β-carotene

- Coumarins: Scopoletin, esculetin, aesculin (leaf)

- Tannins (root)

- Mucilage (root)

- Potassium (leaf)

- Vitamins: A, B, C, D

- Minerals: Iron, copper, calcium, phosphorous and zinc

The bitter sesquiterpene lactones, mostly of the eudesmanolide and germacranolide types, are quite distinctive compared with those of other plants.

Dandelion has been described as an unusually high source of potassium in herbal texts, with the implication that this could be a useful complement to its diuretic action. However, analyses have shown that although levels are relatively high they do not compete with those in tea and coffee (16).

-

Dandelion recipe

I love my liver tea

The liver takes the brunt of the grunt work for metabolising wastes, so use this tea when feeling sluggish, poor digestion or for a detox.

Ingredients

- 4 g dandelion root

- 3 g schisandra (Schisandra chinensis) berries

- 2 g dandelion leaf

- 2 g fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) seed

- 1 g turmeric (Curcuma longa) root powder

- 1 g rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus) leaf

- 1 g liquorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) root

This will serve 2–3 cups of liver-loving tea.

How to make a dandelion liver tea

- Put all of the ingredients in a pot. Add 500 ml/18fl oz freshly boiled filtered water.

- Leave to steep for 10–15 minutes, then strain.

Good move tea

There are only a few ways to move toxins out of the body — so in order to cleanse, it’s essential to ensure the bowels are working properly. Our ‘Good Move tea is especially effective, so proceed with caution. It encourages a relaxed and cleansing bowel motion every day.

Ingredients

- 4 g yellow dock root

- 3 g dandelion root

- 2 g marshmallow root

- 2 g senna leaf

- 2 g orange peel

- 1 g fennel seed

- 1 g liquorice root

This will serve 2–3 cups of bowel moving tea.

How to make a dandelion tea

- Put all of the ingredients in a pot. Add 500 ml (18fl oz) freshly boiled filtered water.

- Leave to steep for 10–15 minutes, then strain.

- Just have one cup a day or you will find yourself needing to visit the toilet frequently. Don’t use it for more than two weeks in a row as senna can cause some dependency and irritate the intestinal lining. Make sure you keep properly rehydrated throughout the day.

Recipes from Cleanse, Nurture, Restore by Sebastian Pole

-

Safety

Dandelion is considered a safe remedy; however, it may cause stomach hyperacidity in some individuals due to the bitter compounds (1,2,14).

The milky latex in the leaves can cause dermatitis in some individuals (1,2,14).

-

Interactions

Dandelion should be used with caution in conjunction with the following medications: Anticoagulants, antidiabetics and quinolone antibiotics. Please consult your medical practitioner for advice if taking these medications (1,2,14).

-

Contraindications

Dandelion should be avoided in cases of occlusion of the biliary or intestinal tract, gallbladder disease or acute gallbladder inflammation. It should also be avoided by those with a known allergy to the Asteraceae family (1,2,14).

-

Sustainability status of dandelion

According to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Plants Status dandelion is classified as ‘Least Concern’ due to its widespread distribution, stable populations and no major threats (18,19,20).

Habitat loss and over-harvesting from the wild are two of the biggest threats faced by medicinal plant species. There are an increasing number of well-known herbal medicines at risk of extinction. We must, therefore, ensure that we source our medicines with sustainability in mind.

The herb supplement industry is growing at a rapid rate and until recent years a vast majority of medicinal plant produce in global trade was of unknown origin. There are some very real and urgent issues surrounding sustainability in the herb industry. These include environmental factors that affect the medicinal viability of herbs, the safety of the habitats that they are taken from, as well as the welfare of workers in the trade.

The botanical supply chain efforts for improved visibility (transparency and traceability) into verifiably sustainable production sites around the world is now certificated through the emergence of credible international voluntary sustainability standards (VSS).

Read our article on Herbal quality & safety: What to know before you buy and Sustainable sourcing of herbs to learn more about what to look for and questions to ask suppliers about sustainability.

-

Quality control

- Country of origin: Eastern Europe

- How sourced: Cultivated/wild-harvested

- Risks: Contamination from pollutants such as heavy metals

- Key marker compounds: Inulin and flavonoids

Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) is an important herbal medicine. The main parts of the dandelion that are used therapeutically are the leaves and roots. The dandelion root contains up to 25% inulin and other polysaccharides, sesquiterpene lactones and caffeic acids (21,22). Sesquiterpenoids are responsible for the bitter taste of the dandelion root. The British Pharmacopoeia (BP) sets a minimum bitterness value of 100 for the root (23) and the leaves contain flavonoids, cinnamic acids and coumarins (21).

The majority of dandelion used is from wild harvested sources, it is a plant that is very adaptable and can grow in a wide variety of different environmental conditions. These environments include saline conditions, which many other plants cannot grow in. Studies have shown that the effect of mild salt stress on dandelion leads to an increase in phenolic compounds such as caffeoylquinic acids (22,24). There is potential to grow dandelion in these more unfavourable conditions and still obtain the desired phytochemical constituents in the plant, and in some cases improve the level of these constituents.

Dandelion is known to accumulate heavy metals particularly in the leaves of the plant. There have been numerous studies that have examined the accumulation of heavy metals in dandelion, particularly in roadside environments (25,26) and the proximity to the road was a key factor (26). Therefore, it is important, particularly when collecting dandelion from the wild, that you consider its proximity to potential sources of environmental contamination.

Herbal medicines are often very safe to take, however, it is important to buy herbal medicines from a reputed supplier. Sometimes herbs bought from disreputable sources are contaminated, adulterated or substituted with incorrect plant matter.

Some important markers for quality to look for would be to look for certified organic labelling, ensuring that the correct scientific/botanical name is used and that suppliers can provide information about the source of ingredients used in the product.

A supplier should be able to tell you where the herbs have come from. There is more space for contamination and adulteration when the supply chain is unknown.

-

References

- Mcintyre A. Complete Herbal Tutor : The Definitive Guide to the Principles and Practices of Herbal Medicine (Second Edition). Aeon Books Limited; 2019.

- Thomsen M. Phytotherapy Desk Reference. 6th ed. Aeon Books; 2022.

- Fan M, Zhang X, Song H, Zhang Y. Dandelion (Taraxacum Genus): A Review of Chemical Constituents and Pharmacological Effects. Molecules. 2023;28(13):5022. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28135022

- Gruszecki R, Walasek-Janusz M, Caruso G, et al. Multilateral Use of Dandelion in Folk Medicine of Central-Eastern Europe. Plants (Basel, Switzerland). 2024;14(1):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14010084

- Vielma H, Matías M, Muñoz-Carrasco N, Berrocal-Navarrete F, González DR, Zúñiga-Hernández J. The Role of Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) in Liver Health and Hepatoprotective Properties. Pharmaceuticals. 2025;18(7):990. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18070990

- American Botanical Council (ABC). Expanded Commission E: Dandelion root with herb. cms.herbalgram.org. Published 1994. Accessed August 2, 2024. http://cms.herbalgram.org/expandedE/Dandelionrootwithherb.html?ts=1550600892&signature=0c7643ae55eb4492b8018a6470e43532&ts=1566006991&signature=6ec2aa1ca4d1b38e0c66a2d5218e5066&utm_medium=sw&utm_source=link&utm_campaign=11-health-benefits-of-dandelion-leaves-and-dandelion-root

- McMullen MK, Whitehouse JM, Towell A. Bitters: Time for a new paradigm. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2015;2015(1):1-8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/670504

- Jalili C, Taghadosi M, Pazouhi M, et al. An Overview of the Therapeutic Potential of Taraxacum Officinale (Dandelion): A Traditionally Valuable Herb with a Reach Historical Background.; 2020. https://www.wcrj.net/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2020/11/e1679.pdf

- Jiang SH, Ping LF, Sun FY, Wang XL, Sun ZJ. Protective effect of taraxasterol against rheumatoid arthritis by the modulation of inflammatory responses in mice. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 2016;12(6):4035-4040. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2016.3860

- Yousefi Ghale-Salimi M, Eidi M, Ghaemi N, Khavari-Nejad RA. Inhibitory effects of taraxasterol and aqueous extract of Taraxacum officinale on calcium oxalate crystallization: in vitro study. Renal Failure. 2018;40(1):298-305. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886022X.2018.1455595

- Clare BA, Conroy RS, Spelman K. The Diuretic Effect in Human Subjects of an Extract of Taraxacum officinale Folium over a Single Day. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2009;15(8):929-934. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2008.0152

- Schütz K, Carle R, Schieber A. Taraxacum—A review on its phytochemical and pharmacological profile. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2006;107(3):313-323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2006.07.021

- Li Y, Chen Y, Sun-Waterhouse D. The potential of dandelion in the fight against gastrointestinal diseases: A review. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2022;293:115272. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2022.115272

- Natural Medicines. Dandelion. naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Published 2024. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/databases/food

- Wirngo FE, Lambert MN, Jeppesen PB. The Physiological Effects of Dandelion (Taraxacum Officinale) in Type 2 Diabetes. The Review of Diabetic Studies. 2016;13(2-3):113-131. https://doi.org/10.1900/rds.2016.13.113

- Gallaher RN, Gallaher K, Marshall AJ, Marshall AC. Mineral analysis of ten types of commercially available tea. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 2006;19:S53-S57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfca.2006.02.006

- RHS. Dandelion / RHS Gardening. www.rhs.org.uk. https://www.rhs.org.uk/weeds/dandelion

- Wildlife Trust. Common dandelion | The Wildlife Trusts. www.wildlifetrusts.org. https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/wildlife-explorer/wildflowers/common-dandelion#:~:text=Common%20Dandelions%20grow%20in%20all

- Khela S. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Taraxacum officinale. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Published April 5, 2013. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/202994/2758459

- NatureServe. Dandelion | NatureServe. www.natureserve.org. Accessed August 2, 2024. https://www.natureserve.org/search/node?keys=dandelion

- Evans WC, Trease GE, Evans D. Trease and Evans’ Pharmacognosy. 16th ed. Saunders/Elsevier; 2009.

- Yan Q, Xing Q, Liu Z, Zou Y, Liu X, Xia H. The phytochemical and pharmacological profile of dandelion. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2024;179:117334-117334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2024.117334

- British Pharmacopoeia Commission. British Pharmacopoeia 2025. London TSO; 2025.

- Zhu Y, Gu W, Tian R, et al. Morphological, physiological, and secondary metabolic responses of Taraxacum officinale to salt stress. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 2022;189:71-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2022.08.002

- Giacomino A, Malandrino M, Colombo ML, et al. Metal Content in Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) Leaves: Influence of Vehicular Traffic and Safety upon Consumption as Food. Journal of Chemistry. 2016;2016:e9842987. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/9842987

- Kajka K, Rutkowska B. Accumulation of selected heavy metals in soils and common dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) near a road with high traffic intensity. Soil Science Annual. 2018;69(1):11-16. https://doi.org/10.2478/ssa-2018-0002