-

Herb overview

Safety

Not recommended in pregnancy or lactation

Can cause skin irritation

Theoretical interaction with CYP3A4 enzymesSustainability

Lower risk

Key constituents

Alkaloids

Lignans

Steroids

FlavonoidsQuality

China and Europe

Wild harvested

Risk of adulteration with Strobilanthes speciesKey actions

Antiviral

Antimicrobial

Anti-inflammatory

ImmunomodulantKey indications

Psoriasis

Cough

Skin rashes

Acute infectionKey energetics

Cold

DryPreperation and dosage

Root and leaf

Up to 20 g per day

9–15 ml per day

-

How does it feel?

-

Into the heart of woad

All parts of woad (Isatis tintoria, ban lan gen) are considered bitter, cold and enter the Blood level, making it effective at clearing heat from even the most potent of contagious infections that have penetrated deeply. However, the leaves primarily disperse making them better suited for manifestations near the surface such as the appearance of macula and purpurea due to Blood leaking from the vessels and pooling under the skin, while the root primarily directs downwards making it better suited for heat lodged in the throat which can be drained downwards (5).

The ability of powdered indigo to treat convulsions and bleeding disorders also comes from this same source. Being salty, very cold and entering the Liver, it can cool the Liver which subsequently cools the Blood which is stored in the Liver and thereby also subdue wind that is generated as result of Liver heat (5). Therefore, it is important that it is used for cases where wind is the result of Liver heat, and not when it is a result of Blood deficiency.

-

What practitioners say

Respiratory system

Respiratory systemWoad (Isatis tintoria, ban lan gen) is one of the core herbs for treating epidemic infections in Chinese medicine, with a particular focus on those that affect the throat and skin such as strep throat and even more serious throat infections like mumps (1,5). However, its cold, draining nature means that it should not be used in all throat infections. While it is a central herb for “warm diseases” (wen bing), it is used rarely, if ever, in cases of “cold damage” (shang han). This means the disease should have predominant signs of heat such as fever and sweating with an aversion to heat, thick phlegm, skin eruptions, a rapid pulse and red tongue with a yellow coat.

If the disease has a cold nature, with chills predominating over fever, tight painful muscles in the upper back, an aversion to the cold and especially drafts, thin mucus, a lack of sweats and a white tongue coating, then it could exacerbate the problem, and a warm or neutral remedy such as liquorice root (Glycyrrhiza glabra, gan cao) or platycodon root (Platycodon grandiflorus, jie geng) might be better indicated instead.

Similarly, if a sore throat is due to a deficiency of moistening yin fluids resulting in a chronic dry throat which may be accompanied by a low grade fever that worsens later in the day, hot flashes or night sweats, then the draining nature of isatis will also be inappropriate and herbs that moisten dryness and nourish yin such as rehmannia (Rehmannia glutinosa, di huang), asparagus (Asparagus racemosus, tian men dong) or dendrobium (Dendrobium, shi hu) are better indicated (1,5).

Skin health

As the lighter, surface part of the plant, woad leaves (da qing ye) are generally preferred when an epidemic infection affects the skin causing maculae, papulae, rashes, sores or boils (5). This equates to a number of modern infectious diseases, such as measles, meningitis, scarlet fever or erysipelas, and various poxes such as chickenpox and monkeypox (1,7). For these uses it can be decocted and taken internally where its antibacterial and antiviral properties can assist in fighting the infection. For topical applications, the powder (qing dai) is generally preferred, where it can be mixed with other powdered ingredients, such as powdered phellodendron bark, gypsum and talcum or powdered clam shell, to be applied to swollen, weeping, inflamed (damp-heat) skin conditions (8).

It is generally mixed with a medium and applied under a plaster to disguise the blue-green staining that will naturally occur. This use for skin conditions has also extended to the treatment of psoriasis, where it has been investigated for both internal and topical applications. Topical is generally preferred to avoid the systemic side effects on the digestive system although decoctions containing indigo powder have also demonstrated a good therapeutic effect with minimal side effects (3,4).

-

Woad research

Woad (Isatis tinctoria) Isatis indigotica: A review of phytochemistry, pharmacological activities and clinical applications

This study reviewed the current evidence surrounding the pharmacology and clinical uses of woad. The authors concluded it has antiviral, antibacterial, immunoregulatory, anti-inflammatory, and cholagogic effects with particular inhibitory activity against influenza, hepatitis B, mumps, herpes simplex, cytomegalovirus, and coxsachievirus with clinical applications for viral influenza, parotitis and viral hepatitis. They conclude by suggesting it may be beneficial for the prevention and treatment of Covid-19 (9).

Isatis indigotica: From (ethno) botany, biochemistry to synthetic biology

The authors meticulously describe the differences between asian Isatis indigotica and european I. tinctoria, finding much higher levels of indole alkaloid derivatives, quinolines, and flavonoids in I. indigotica, while I. tinctoria had higher organic acid derivatives.

The lignans, indole alkaloids and their derivatives are identified as the major active ingredients with antiviral, anti-inflammatory and anticancer activities. They also provide detailed information on the metabolic pathways for the main constituents and note that attempts to genetically engineer the plant for insect resistance was the first such attempt to genetically engineer a medicinal crop for pest control (10).

Evidence and potential mechanism of action of indigo naturalis and its active components in the treatment of psoriasis

This study evaluated research that investigated the use of indigo powder in the treatment of psoriasis. Both indigo powder and its main active constituent indirubin showed significant reductions in psoriasis severity through the inhibition of hyperproliferation and differentiation of keratinocytes and expression of pro-inflammatory mediators. The main side effects were an increase in gastrointestinal reactions among the groups that took the isatis systemically with some non-significant reports of skin dryness, itching, dry mouth and erythema among the topical groups (4).

Indigo naturalis as a potential drug in the treatment of ulcerative colitis: A comprehensive review of current evidence

This review examined the current evidence on the use of indigo powder in the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Key components identified were Indirubin, indigo, isatin, tryptanthrin, and β-sitosterol through aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway activation, immune regulation, oxidative stress inhibition, and intestinal microbial modulation.

It was particularly useful in severe cases or in those who do not respond to or have poor efficacy with existing therapies but carried a risk of pulmonary hypertension which suggested rational application (11).

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

-

What can I use woad for?

Isatis root is commonly used for throat infections, including sore throat and mumps, while the leaves are often used for dispersing rashes that are the result of external infections that have penetrated deeply. These can be quite severe, including convulsions, delirium and incoherent speech (1). While this is a common herb throughout Chinese history, these uses have also sparked interest from western herbalism into its antiviral effects for respiratory infections (2).

Recently, indigo powder has attracted attention for its potential in the treatment of psoriasis where it has demonstrated antiproliferative, anti-inflammatory and anti-angiogenic effects (3,4).

-

Did you know?

Woad (Isatis tinctoria) is also famous for being the blue dye that ancient celtic warriors used to paint themselves before battle, however, this is unlikely to be true (12). It is based on Julius Caesar’s description of the English celts and the actual words he uses are that they dye their bodies with vitro, meaning “glass” to give their bodies a blueish colour. Historians have assumed this to mean woad, but indigo is neither a good body paint, tending to streak easily, then dry and flake off, nor tattoo ink, as it is caustic, resulting in scarring but no retention of the blue colour.

The Chinese name for woad leaf, da qing ye, literally means “big blue-green leaf” and may refer to many plants with this colouration. It is conjectured that historical references to this medicine may not have actually referred to Clerodendrum cyrtophyllum, also known as mayflower glorybower or da qing ye, which has superior antiviral properties, albeit with inferior antipyretic and analgesic actions (5). This herb is now only used in some areas of Jiangxi province.

-

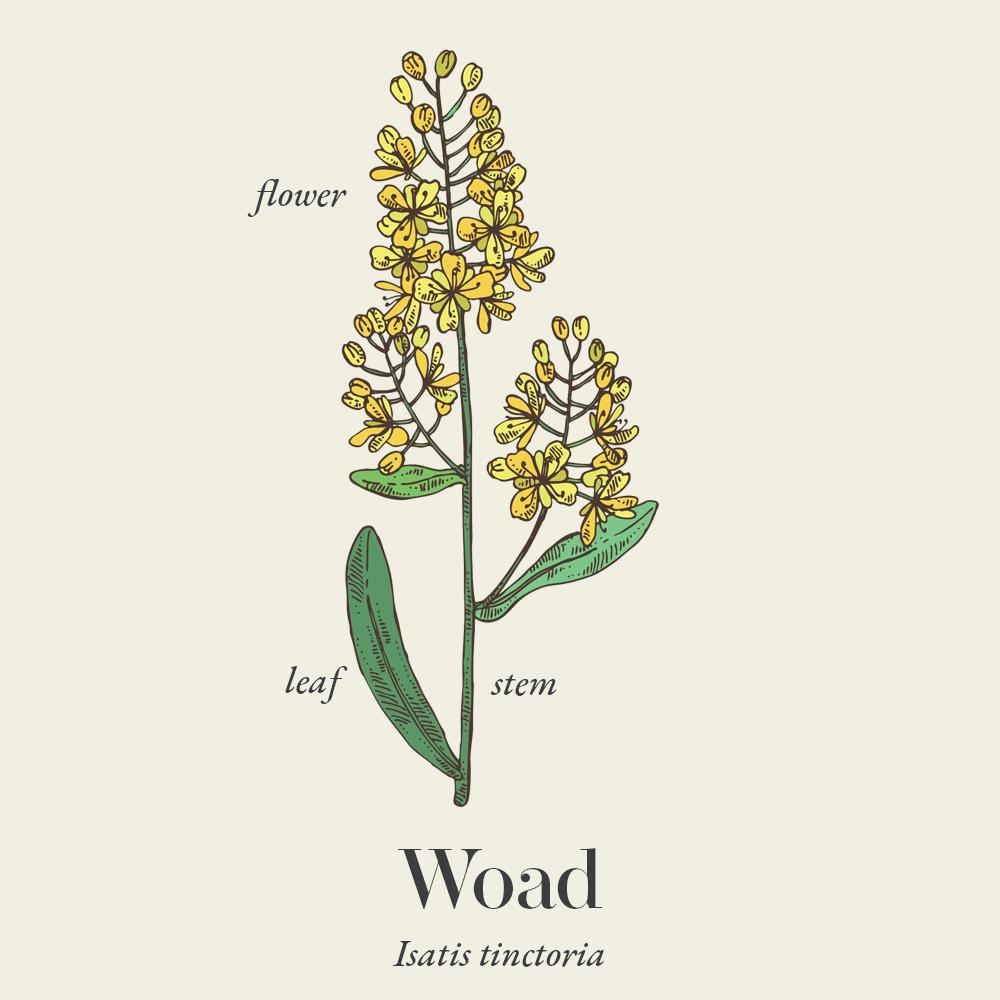

Botanical description

Woad can be an annual, biennial or perennial with ovate to oblong shaped basal leaves and smaller, arrow-shaped, stalkless stem leaves, and loose racemes or panicles of yellow flowers (37).

-

Common names

- Woad

- Van lan gen

- Da qing ye

- Qing dai

-

Habitat

I. indigotica originated in northwest China before spreading to the northeast, eastern and central China (38), where it is found growing largely on waste ground or dry, rocky areas (37). I. tinctoria is native to central and southern Europe, and naturalised in south and central England where it grows on cliffs and cornfields, often on chalky soils (39).

-

How to grow woad

Sow seeds in spring in situ. Fresh seed can also be sown in situ in late summer, where it will take 20 months to flower but will produce more leaves (39).

-

Herbal preparation of woad

- Raw root or leaf

- Indigo powder (qing dai): Made by soaking the stems and leaves of I. indigotica, Baphicacanthus cusia and Polygonum tinctorium until they rot, removing them, adding lime slurry and drying the liquid into a powder.

-

Plant parts used

- Whole root (ban lan gen)

- Whole leaf (da qing ye)

-

Dosage

- Tincture (1:3 25%, 1:3 45%): 3–5 ml three times a day for three weeks, then take a break (15–17)

- Glycerine macerate (1:1 0%): 0.5–1 ml three times a day (18)

- Infusion/decoction: 9–15 g of root or leaf, or up to 20 g of leaf (1,5,19)

- Other preparations: 1–3 g indigo powder (qing dai) added to strained decoctions (19), or 0.6–1 g as a powder in pills (5)

-

Constituents

- Alkaloids

-

- Indigotin: The compound that gives indigo its characteristic blue-black colour, and found in the whole herb where it is used as a marker compound for the identification and quality of isatis leaf where it should be present in quantities not less than 2.0% (9,19). It is stored as indican in the living plant and released after plant death (10).

- Indirubin: The main active ingredient of indigo with a red colour that gives indigo dyes a purple hue , and valued medicinally for its anticancer, anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties (20,21). It is found in the whole herb and used as a marker compound for the identification and quality of isatis leaf where it should be present in quantities not less than 0.02%, and also as a quality marker for powdered indigo where it should be present in quantities of not less than 0.13% (9,19). It is also a marker of indigo from plant origin, since it is not present in synthetic indigo (20). It is stored as indican in the living plant and released after plant death (10).

- Isaindigotone: Found in the whole herb and displays antiviral, antifungal and anticancer activities (9,22,23).

- Tryptanthrin: Found in the whole herb [9] and initially attracting attention to this plant for its anti-inflammatory potential through cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition (9,24). It has also been investigated for its potent anticancer activities, whilst also displaying antiprotozoal, antiallergic, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activity (25,26).

- Isatin: Found only in the root and obtained after the oxidation of indigotin is complete (9,10). It has attracted considerable interest as a potential antiviral and a potential scaffold for therapeutic complexes for a number of biological applications (27,28).

- Lignans

- Lariciresinol: Found only in the aerial parts, although isolariciresinol is found in the whole plant and its glycoside is found in the root (9). It displays potent antioxidant effects, antimicrobial effects against foodborne pathogens, anticancer effects through inhibition of proliferation and induction of apoptosis, and anti-inflammatory and antidiabetic effects (29).

- Flavonoids

- Isovitexin: Found in the whole herb [9] and providing multiple health benefits through antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antibacterial, and neuroprotective mechanisms but with particular interest coming from studies into cardiovascular protection, diabetes and obesity management, cholesterol lowering, anticancer effects and management of chronic inflammation, oxidative stress and prevention of neurodegenerative disorders 9,30).

- Liquiritigenin: Found in the whole herb [9] and investigated for antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, anti-ageing (skin), antimicrobial, antiobesity, antidiabetic and anticancer activities 9,31).

- Steroids

- β-sitosterol: Found in the whole herb and investigated as a potential anticancer agent, especially for early stages of prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia in younger men where the side effects of clinical drugs may be undesirable (9,32,33).

- Daucosterol: Glucoside of β-sitosterol of found only in the root with antioxidant, antidiabetic, hypolipidemic, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, neuroprotective, and anticancer activities (9,34).

- Anthraquinones

- Emodin: Found only in the root and recognised as a protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor and as an anticancer drug, recently studied for its potential to combine with allopathic medicine to minimise toxicity and enhance efficacy through anti-ulcer, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic, hepatoprotective, neuroprotective, antimicrobial, muscle relaxant, immunosuppressive and antifibrotic activities (35).

- Sulphur compounds

- Epigoitrin: Found only in the root and used as a marker compounds for the identification and quality of isatis root where it should be present in quantities not less than 0.02% (19). It displays antiviral effects, improving the resistance to infection in stressed mice (36).

-

Woad recipe

Angelica, gentian and aloe to treat severe heat

Angelica (Angelica sinensis), gentian (Gentiana lutea) and aloe (Aloe vera) pills are a classic formulation from the 12th century that uses indigo for the treatment of severe heat affecting the Liver and Gall Bladder producing headache, vertigo, restlessness, delirious speech, mania and tremors, twitching or convulsions in children (8). There may also be constipation, dark and rough urination, or blockage of the throat with difficulty swallowing.

It is an extremely cold and draining formula that directs Fire downwards in order to treat a condition where the intensity of the heat is starting to take form. As such, it should only be used in excess conditions and avoided in cases of deficiency, especially deficiency of the digestive system (Spleen). In modern terms this may equate to a number of inflammatory disorders such as hepatitis, cholecystitis, cholelithiasis, biliary ascariasis, gastritis, gastroenteritis, pharyngitis, otitis media, cystitis, urethritis, vaginitis, chronic myelogenous leukemia, febrile disorders and acne (13).

Ingredients

- 30 g dang gui (Angelica sinensis, dang gui)

- 30 g gentian (Gentiana lutea, long dan cao)

- 30 g gardenia (Gardenia jasminoides / zhi zi)

- 30 g coptis (Coptis chinensis, huang lian)

- 30 g amur corktree (Phellodendron, huang bai)

- 30 g Baical skullcap (Scutellaria baicalensis, huang qin)

- 15 g aloe (Aloe vera, lu hui)

- 15 g Indigo naturalis (qing dai)

- 15 g rhubarb (Rheum palmatum,da huang)

- 4.5 g Indian costus auklandia (Dolomiaea costus, mu xiang)

- 1.5 g musk (Moschus, she xiang)

How to make angelica gentian and aloe pills

- Grind all the herbs into a powder.

- Form the powder into pills with honey. For adults, make them the size of an adzuki bean, or the size of hemp seeds for children.

- Take 20 pills per day with a decoction of fresh ginger (Zingiber officinale), modern texts advise 6 g twice per day.

- Avoid any substance that might add heat to the body.

- Musk may have to be substituted due to it being an animal product. Its function in the formula is to be warm and acrid, countering the cold, draining action of the other herbs, to preserve the qi dynamic , and to revive consciousness in patients where this is affected. Suitable alternatives could include sweet flag (Acorus calamus) and frankincense (Boswellia serrata) which also have warm, aromatic, consciousness restoring properties (8,13).

-

Safety

Oral use is generally safe with only occasional reports of gastrointestinal disturbances (1). Topical and oral administration can cause allergic skin reactions (1,5). There is insufficient evidence to attest to its safety in pregnancy and lactation and, therefore, it is recommended to consult with a professional medical herbalist in these instances (1,5).

-

Interactions

Indirubin, a constituent of I. indigotica, activates CYP3A4 gene transcription so may interfere with drugs that are metabolised through this pathway, although clinical relevance of this is not yet known (14).

-

Contraindications

Traditional contraindications come from its cold, draining nature and include cold in the Stomach, deficiency cold of the Spleen, or heat when it is due to deficiency (1,5).

-

Sustainability status of woad

Isatis tinctoria is listed on the IUCN redlist as ‘least concern’, and the plant is not considered to be at threat due to its prolific growing habits (40,41). In some areas of the world, including the USA it is considered an invasive weed and difficult to eradicate (42).

Habitat loss and over-harvesting from the wild are two of the biggest threats faced by medicinal plant species. There are an increasing number of well-known herbal medicines at risk of extinction. We must, therefore, ensure that we source our medicines with sustainability in mind.

The herb supplement industry is growing at a rapid rate and until recent years a vast majority of medicinal plant produce in global trade was of unknown origin. There are some very real and urgent issues surrounding sustainability in the herb industry. These include environmental factors that affect the medicinal viability of herbs, the safety of the habitats that they are taken from, as well as the welfare of workers in the trade.

The botanical supply chain efforts for improved visibility (transparency and traceability) into verifiably sustainable production sites around the world is now certificated through the emergence of credible international voluntary sustainability standards (VSS).

Read our article on Herbal quality & safety: What to know before you buy and Sustainable sourcing of herbs to learn more about what to look for and questions to ask suppliers about sustainability.

-

Quality control

Woad (Isatis tinctoria) A notable characteristic of indigo (qing dai) is that its main compounds, indigotin and indirubin, have poor solubility in water (9). This means that common adulterants such as blue paint can be detected by mixing some indigo with water and observing the reaction. True indigo will not dissolve while common paints will turn the water blue.

There have also been reports of widespread adulteration of the raw root and leaf in the Hong Kong markets (43). The main adulterant was Strobilanthes species (syn. Baphicacanthis), more available in southern China and known colloquially as “southern indigo” (nan ban lan gen or nan da qing ye). It has a similar morphology and is also antiviral, but does not contain the essential compounds epigoitrin and indirubin, making it weaker at direct viral inhibition, and preferred for clearing viral material after infection.

Some differentiating features of the Isatis root include being cylindrical, slightly twisted with an enlarged head, grayish-yellow longitudinal wrinkles, long raised horizontal lenticles, a solid, but slightly soft texture, yellowish white cortex and yellow woody portion (44). Meanwhile Stobilanthes roots are semi-cylindrical, generally curved with numerous branches, have grayish-brown exterior with enlarged joints and thin roots or remnants of rhizomes on the upper part, hard but brittle texture, a blue-gray woody potion and a pith (44).

Isatis leaves should be a blue-green colour with a broad yellowish-white mid-vein, long with tapering bases and a broadly rounded tip, while Strobilanthes are blackish-green in colour, shorter, elliptic to ovate with a pointed tips and saw-toothed margins (45). In processed material, this adulteration may only be detectable through chemical analysis of these chemical markers or genetic analysis. Since Hong Kong is a major distribution centre for medicinal herbs worldwide, this problem may affect the entire international market (43).

-

References

- Chen JK & Chen TT. Chinese Medical Herbology and Pharmacology. City of Industry: Art of Medicine Press. 2012.

- Speranza J, Miceli N, Taviano MF, et al. Isatis tinctoria L. (Woad): A Review of its Botany, Ethnobotanical Uses, Phytochemistry, Biological Activities, and Biotechnological Studies. Plants (Basel). 2020;9(3):298. Published 2020 Mar 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9030298

- Zhang Q, Xie J, Li G, et al. Psoriasis treatment using Indigo Naturalis: Progress and strategy. J Ethnopharmacol. 2022;297:115522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2022.115522

- Wang C, Yang P, Wang J, et al. Evidence and potential mechanism of action of indigo naturalis and its active components in the treatment of psoriasis. Ann Med. 2024;56(1):2329261. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2024.2329261

- Bensky D, Clavey S & Stoger E. Chinese Herbal Medicine: Materia Medica, 3rd Edition. Seattle: Eastland Press. 2004.

- Dioscorides. De Materia Medica. Translated by Osbaldeston TA, Wood RPA. Johannesburg: Ibidis Press. 2000.

- Rong HG, Zhang XW, Han M, et al. Evidence synthesis of Chinese medicine for monkeypox: Suggestions from other contagious pox-like viral diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1121580. Published 2023 Mar 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2023.1121580

- Scheid V, Bensky D, Ellis A, Barolet R. Chinese Herbal Medicine: Formulas & Strategies, 2nd edition. Seattle: Eastland Press. 2009.

- Chen Q, Lan HY, Peng W, et al. Isatis indigotica: a review of phytochemistry, pharmacological activities and clinical applications. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2021;73(9):1137-1150. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpp/rgab014

- Feng J, Huang D, Yang Y, et al. Isatis indigotica: from (ethno) botany, biochemistry to synthetic biology. Mol Hortic. 2021;1(1):17. Published 2021 Dec 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43897-021-00021-w

- Hu Y, Chen LL, Ye Z, et al. Indigo naturalis as a potential drug in the treatment of ulcerative colitis: a comprehensive review of current evidence. Pharm Biol. 2024;62(1):818-832. https://doi.org/10.1080/13880209.2024.2415652

- Tastes of History. Dispelling Some Myths: Woad. Published December 28, 2021. Updated November 7, 2025. Accessed November 27, 2025. https://www.tastesofhistory.co.uk/post/dispelling-some-myths-woad

- Chen JK & Chen TT. Chinese Herbal Formulas and Applications. City of Industry: Art of Medicine Press. 2016.

- Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre. Isatis Root. Published May 4, 2022. Accessed November 30, 2025. https://www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/integrative-medicine/herbs/isatis-root

- Bristol Botanicals. Qing Dai tincture (Isatis tinctoria) 1:3 25%. Published 2025. Accessed November 30, 2025. https://www.bristolbotanicals.co.uk/pr-1128

- Herbal Apothecary UK. Isatis tinctoria / BAN LAN GEN / 1:3 25%. Published 2025. Accessed November 30, 2025. https://herbalapothecaryuk.com/products/isatis-tinctoria-ban-lan-gen-13-25

- Napiers. Ban Lan Gen Tincture (Isatis tinctoria). Published 2025. Accessed November 30, 2025. https://napiers.net/products/ban-lan-gen-tincture-isatis-tinctoria

- Lyme Herbs. Isatis Alcohol Free Extract 1:1 (100ml). Published 2025. Accessed November 30, 2025. https://lymeherbs.eu/extracts-11-100-ml/1064-isatis-alcohol-free-extract-11-100ml-5907775711443.html

- Taiwan Herbal Pharmacopeia 4th Edition, English Version. Taiwan: Ministry of Health of Welfare. 2022.

- Ellis, C. The Surprise of Indirubin! Natural Dye: Experiments and Results. Published November 7, 2021. Accessed November 27, 2025. https://blog.ellistextiles.com/2021/11/07/the-surprise-of-indirubin/

- Yang L, Li X, Huang W, Rao X, Lai Y. Pharmacological properties of indirubin and its derivatives. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;151:113112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113112

- Liu S, Xu Y, Li M, et al. Design, synthesis, structural optimization, and biological activity research of quinazolinone alkaloid isaindigotone. Pest Manag Sci. Published online October 6, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1002/ps.70290

- Du K, Ma W, Yang C, et al. Design, synthesis, and cytotoxic activities of isaindigotone derivatives as potential anti-gastric cancer agents. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2022;37(1):1212-1226. https://doi.org/10.1080/14756366.2022.2065672

- Hamburger M. Isatis tinctoria – From the rediscovery of an ancient medicinal plant towards a novel anti-inflammatory phytopharmaceutical. Phytochemistry Reviews. 2002;1(3):333-344. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026095608691

- Zhou X. Recent advances of tryptanthrin and its derivatives as potential anticancer agents. RSC Med Chem. 2024;15(4):1127-1147. Published 2024 Jan 4. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3MD00698K

- Kaur R, Manjal SK, Rawal RK, Kumar K. Recent synthetic and medicinal perspectives of tryptanthrin. Bioorg Med Chem. 2017;25(17):4533-4552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2017.07.003

- Elsaman T, Mohamed MS, Eltayib EM, et al. Isatin derivatives as broad-spectrum antiviral agents: the current landscape. Med Chem Res. 2022;31(2):244-273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00044-021-02832-4

- Bugalia S, Dhayal Y, Sachdeva H, et al. Review on Isatin- A Remarkable Scaffold for Designing Potential Therapeutic Complexes and Its Macrocyclic Complexes with Transition Metals. J Inorg Organomet Polym Mater. Published online May 7, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10904-023-02666-0

- Sigma-Aldrich. (+)-Lariciresinol. Accessed November 27, 2025. https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/GB/en/product/sigma/06892

- Yan W, Cheng J, Xu B. Dietary Flavonoids Vitexin and Isovitexin: New Insights into Their Functional Roles in Human Health and Disease Prevention. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(14):6997. Published 2025 Jul 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26146997

- Sajeev A, Aswani BS, Alqahtani MS, Abbas M, Sethi G, Kunnumakkara AB. Harnessing Liquiritigenin: A Flavonoid-Based Approach for the Prevention and Treatment of Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2025;17(14):2328. Published 2025 Jul 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17142328

- Wang H, Wang Z, Zhang Z, Liu J, Hong L. β-Sitosterol as a Promising Anticancer Agent for Chemoprevention and Chemotherapy: Mechanisms of Action and Future Prospects. Adv Nutr. 2023;14(5):1085-1110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advnut.2023.05.013

- Macoska JA. The use of beta-sitosterol for the treatment of prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Am J Clin Exp Urol. 2023;11(6):467-480. Published 2023 Dec 15.

- El Omari N, Jaouadi I, Lahyaoui M, Benali T, Taha D, Bakrim S, El Menyiy N, El Kamari F, Zengin G, Bangar SP, et al. Natural Sources, Pharmacological Properties, and Health Benefits of Daucosterol: Versatility of Actions. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(12):5779. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12125779

- Semwal RB, Semwal DK, Combrinck S, Viljoen A. Emodin – A natural anthraquinone derivative with diverse pharmacological activities. Phytochemistry. 2021;190:112854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytochem.2021.112854

- Luo Z, Liu LF, Wang XH, et al. Epigoitrin, an Alkaloid From Isatis indigotica, Reduces H1N1 Infection in Stress-Induced Susceptible Model in vivo and in vitro. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:78. Published 2019 Feb 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2019.00078

- Royal Horticultural Society. Isatis tinctoria var. Indigotica. Accessed November 30, 2025. https://www.rhs.org.uk/plants/243559/isatis-tinctoria-var-indigotica/details

- Yong S, Wang CX, Min W, et al. Study of the origin and evolution of Isatis indigotica fortune via whole-genome resequencing. Industrial Crops and Products. 2025;228:120873-120873. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2025.120873

- [39] Plants for a Future. isatis tinctoria – L. Accessed November 30, 2025. https://pfaf.org/user/Plant.aspx?LatinName=isatis+tinctoria

- Bulińska Z, Magos J, Strajeru S, et al. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Isatis tinctoria. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Published April 13, 2010. Accessed December 20, 2025. http://iucnredlist.org/species/176538/7261792

- Dupré J, Joly N, Vauquelin R, et al. Isatis tinctoria L.—From Botanical Description to Seed-Extracted Compounds and Their Applications: An Overview. Plants. 2025;14(15):2304-2304. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14152304

- Ahmad T, Jabran K, Farooq S, Isik D, Hussain MI, Bajwa AA. The biology, ecology and management of Isatis tinctoria L.: An important weed of rangelands. Advances in Weed Science. 2025;43. https://doi.org/10.51694/advweedsci/2025;43:00017

- Ngai HL, Cheng SW, Tse TS, Lee HK, Shaw PC. Quality assessment of medicinal material Daqingye and Banlangen from Isatis tinctoria Fort. reveals widespread substitution with Strobilanthes species. PLoS One. 2025;20(5):e0323084. Published 2025 May 7. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0323084

- Zhao Z, Chen H. Chinese Medicinal Identification: An Illustrated Approach. Taos: Paradigm Publications. 2014

- Leon C & Lin YL. Chinese Medicinal Plants, Herbal Drugs and Substitutes: an identification guide. Kew: Kew Gardens Publishing. 2017.