-

Herb overview

Safety

Detoxifying effects can be associated with temporary exacerbations of skin problems

Avoid with diarrhoea and anticoagulantsSustainability

Low risk/Green

FairWild certified sources availableKey constituents

Sesquiterpene lactones

InulinQuality

Europe, North Asia and North America

Both wild-harvested and commercially cultivated

Risks of substitution with other Arctium speciesKey actions

Bitter

Alterative

Diuretic

DepurativeKey indications

Acne

Eczema

Arthritis

ConstipationKey energetics

Cooling

MoisteningPreperation and dosage

Root, and seed

Tincture (1:5| 25%): 6–12 ml daily

Decoction: 3–18 g per day

-

How does it feel?

The taste of burdock root is a mix of slight acridity and slight bitterness, followed by a mucilaginous property. None of these tastes dominate, though overall it is the bitter and mucilaginous properties that linger longest on the palate.

-

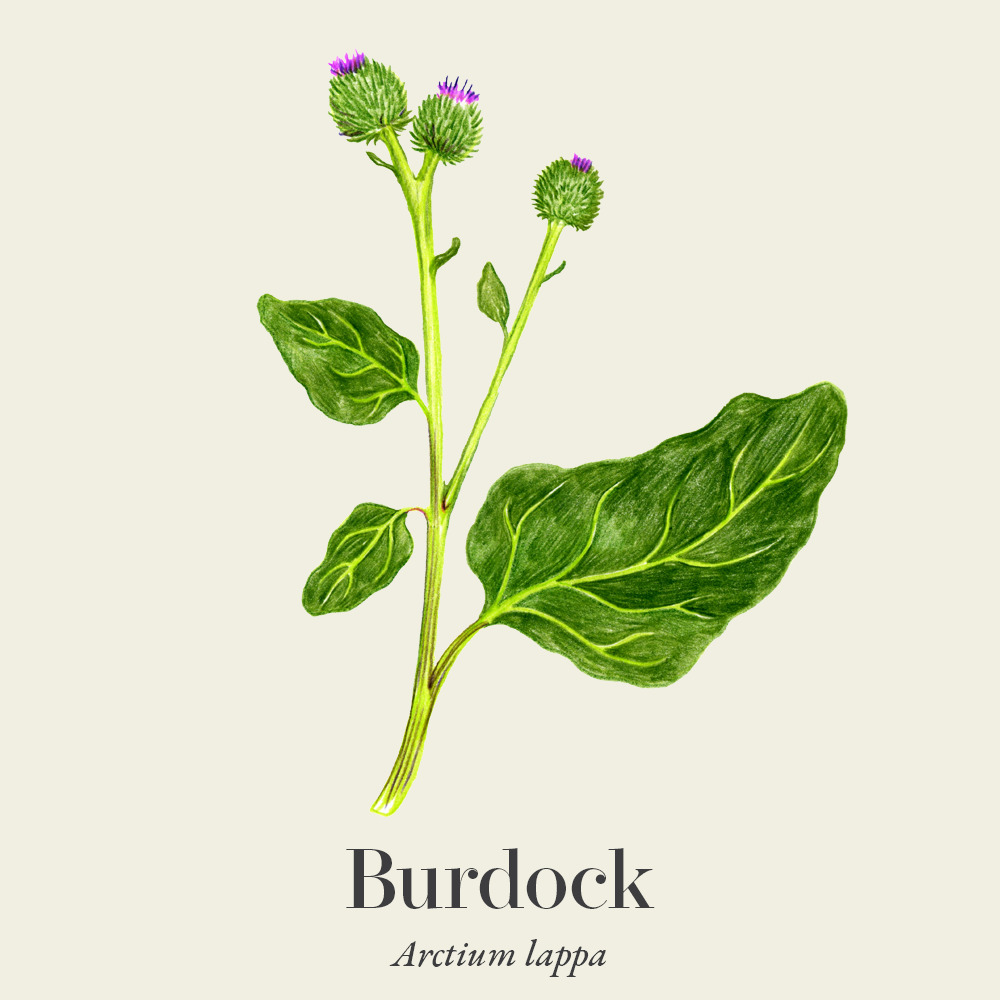

Into the heart of burdock

Burdock (Arctium lappa) Burdock is one of the most notable internal treatments for skin problems in traditional Western herbal medicine. Its powerful eliminatory properties help to detoxify metabolic waste through the urinary and digestive systems. In modern clinical practice, burdock is understood to purify the blood by drawing out toxins into the circulation and reducing inflammation (1). As a result, burdock can sometimes temporarily exacerbate skin problems, a factor which can be mediated by combining it with other strong eliminatory and laxative remedies including artichoke leaf (Cynara scolymus), dandelion root (Taraxacum officinale), yellow dock (Rumex crispus) or cleavers (Galium aparine).

A theory commonly adopted within clinical practice is the understanding that due to the distribution of the body’s fluids as predominantly in the tissues, and a lesser percentage in the plasma (circulation), ingestion of burdock could lead to a theoretical risk for toxaemia. This can result from rapid metabolite movement into clearance mechanisms, which could overwhelm the normal eliminatory processes and result in increased inflammation or an exacerbation of skin reactions (1,5). In order to mitigate this risk, the ‘drawing’ action of burdock is combined with the eliminatory actions of other cleansing remedies.

The advised method to use burdock is to titrate the dosage, starting with a low dose and increasing incrementally, as well as using it in combination with other remedies previously mentioned.

Burdock was first cited in a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) text in 500 CE, burdock seed (niu bang zi) belongs to the TCM category of herb, “cool, acrid herbs that release the exterior”. Of the seed and the root, it is typically the seed that is used medicinally in TCM. The root is more commonly used in dietary therapy, particularly in Japan.

Niu bang zi is specifically indicated in cases of exterior wind-heat (e.g., common colds and flus) accompanied by fever and sore, red and swollen throats.

In TCM dermatology, it is used to relieve ‘toxic heat’ from the skin in cases of red swellings, eczema, acute febrile rashes, mumps and carbuncles. It is also employed to vent rashes in the early stage of measles.

Used as a seed, burdock is lubricating to the intestines and used in cases of constipation caused by the aforementioned ‘exterior wind-heat’.

-

What practitioners say

Burdock is a popular and highly valued remedy in Western herbal practice. It is most often applied as a carefully administered component of detoxifying regimes to reduce inflammatory conditions affecting the skin and joints.

Immune system

Burdock is a mild diaphoretic (promotes sweating) which also supports effective movement throughout the lymphatic system, an essential aspect of the immune system. This contributes to its effectiveness as a cleanser or purifier by helping to eliminate harmful toxins from the body. Supporting lymphatic flow helps to support the immune response in cases of infection and fluid imbalance. Burdock is often applied by herbalists to stimulate movement in the lymphatic system (1).

Integumentary system

Burdock is one of the most effective remedies for the treatment of psoriasis, eczema and dermatitis (8). It is also used in a number of other inflammatory skin conditions; this is largely due to its unique effect on both the liver and the lymphatic system (1,3). It is specific in the treatment of seborrhoeic skin conditions (3).

Digestive system

Burdock is a gentle bitter digestive, combining well with dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) to improve appetite and stimulate digestive function especially in recovery from illness (1). Burdock is indicated as an appetite stimulant for anorexia nervosa. Burdock root is rich in inulin and fibre which helps to alleviate constipation and support digestion (9).

Urinary system

Burdock exerts its diuretic action by increasing urine production and elimination through the urinary system. Through increasing urine output, it helps to facilitate the removal of metabolic waste and can be used to treat minor urinary tract infections and reduce fluid retention (3).

Endocrine system

Burdock root has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity and reduce fasting blood glucose levels. This suggests burdock root can be used alongside other herbs to help manage conditions including insulin resistance, diabetes and metabolic syndrome (10).

Musculoskeletal system

Burdock has both diuretic and anti-inflammatory properties, which help to reduce inflammatory markers in rheumatic conditions including osteoarthritis, gout and rheumatoid arthritis . It also helps to reduce oxidative stress, which is a contributing factor to inflammatory disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis (1,11).

-

Burdock research

Burdock (Arctium lappa) Effects of burdock tea on recurrence of colonic diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding: An open-labelled randomised clinical trial

Acute colonic diverticulitis (ACD) is a common gastrointestinal condition, with clinical presentation ranging from mild abdominal pain to peritonitis with sepsis. Colonic diverticular bleeding (CDB) is the most common cause of lower gastrointestinal bleeding in adults. The experimental group received 1.5 g of burdock tea three times a day, and the control group did not receive any treatment.

There was a lower recurrence of ACD 5/47 (10.6%) vs 14/44 (31.8%) in the control group. The recurrence-free duration was also observed in the burdock tea at 59.3 months vs 45.1 months for the control group. This randomised controlled trial demonstrated that daily consistent consumption of burdock tea could be effective for the prevention and reduction of ACD recurrence but not for CDB recurrence (12).

Effects of Arctium lappa L. (burdock) root tea on inflammatory status and oxidative stress in patients with knee osteoarthritis

A study was conducted on 36 people between 50–70 years old suffering from bilateral knee osteoarthritis. They were given three cups a day of burdock root tea (2 g of tea steeped in 150 ml of boiled water for 10 minutes) for six weeks. Blood lipid profiles and blood pressure were measured, and a significant improvement was seen in both parameters. The patients in the burdock group had significantly decreased levels of inflammatory markers (IL-6, hs-CRP and malondialdehyde) with a significant increase in antioxidant activity (13).

A review of the pharmacological effects of Arctium lappa (burdock)

A review of the pharmacological activity of burdock showed it has anti-inflammatory activities via inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase, and, therefore, inhibition of nitric oxide production. It has also been shown to suppress pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, inhibit nuclear factor-kappa B pathway and activate antioxidant enzymes which increases free radical scavenging and decreases oxidative stress. These mechanisms are thought to be the basis of burdock’s anti-inflammatory action and may be responsible for its action in supporting inflammatory skin conditions, such as eczema and dermatitis (14).

-

Historical use of Burdock

The root has been used in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) for relieving congestion and toxicity, with more recent references for its use in treating diabetes (6). The seeds are used in TCM for septic conditions, boils, abscesses, and inflammation in the throat. They are also used as cooling diaphoretic remedies in fever management and a diuretic formerly applied to dropsy and other cases of oedema.

Burdock forms one of the four key ingredients along with sheep sorrel (Rumex acetosella), slippery elm (Ulmus rubra) and rhubarb root (Rheum officinale) in ESSIAC — a formulation originally promoted as an alternative cancer treatment by a Canadian nurse Rene Caisse (ESSIAC is her name spelt backwards). This blend is regarded as a powerful cleansing regime (7).

-

Burdock's herbal actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

-

Burdock's energetic qualities

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

Chinese energetics

-

What can I use burdock for?

Burdock (Arctium lappa) In European traditions, burdock is one of the classic blood cleansers or purifiers, also known as depurative or alterative remedies. Herbs in this category were seen to reduce toxins by increasing metabolic processes of elimination through the liver, kidneys and bowel and have a particular application in the treatment of chronic skin conditions, including eczema or psoriasis. The root is most commonly used, however, the seeds have also been used for similar purposes and were the choice remedy particularly among European settlers in North America (1,2).

The European Medicines Agency describes burdock as a traditional herbal medicine to increase urine output, helping to eliminate toxins during minor urinary tract infections, for temporary loss of appetite and for the treatment of seborrhoeic skin conditions (seborrheic eczema is associated with blocked sebaceous glands, especially around hair follicles, and is similar to acne) (3).

These compilations of traditional reputations distil into burdock’s three core actions:

- As a diuretic to reduce fluid congestion and relieve urinary discomforts.

- As a bitter digestive.

- As a detox remedy especially in cases of eczema or other skin conditions.

The leaves, seeds and root were also used externally, all having a soothing mucilaginous property and in the case of the seeds an oiliness that was highly regarded as a skin tonic. As Culpeper noted: “The Burdock leaves are cooling and moderately drying… wherby good for old ulcers and sores”(4).

-

Did you know?

The well known dandelion and burdock drink originated in Britain from the Middle Ages as a light fermented decoction of the two roots, often associated with the start of spring detoxification. The popular carbonated drink was launched in 1871 in Yorkshire, to become a global commodity in the 20th century (15).

In 1941, burdock was the inspiration for the invention of velcro. A swiss engineer George de Mestral was curious about the way the burrs from burdock were sticking to his dog’s fur, and through examination under a microscope he took inspiration from the hook like structure of the burs to create velcro (16).

It is an important herb in one of the most popular TCM formulas, yin qiao san (honeysuckle and forsythia powder), which is taken in cases of colds and flus with fever and sore throats (6).

-

Botanical description

A strong biennial plant extending up to two metres high, marked out by its very large ovate-cordate leaves reaching up to 45 cm across, though getting smaller up the stem; they are generally smooth above and with white cottony down underneath.

The other distinguishing marks are the flowers, borne in clusters at the top of the stems, globular in shape and covered with a dense array of stiff hooked bracts that cling to anything coming in contact; enclosed inside are purple florets, and after fruiting large achenes with a short pappus of stiff hairs on each.

The long root, up to three feet long, runs straight down into the subsoil; when chopped and dried it is covered externally with brown cork and longitudinally wrinkled, the inner surface mealy and buff-white (19).

-

Common names

- Great burdock

- Beggars buttons

- Thorny burr

- Klette (Ger)

- Bardane (Fr)

- Bardana (Ital, Sp)

- Niu bang zi (seed)

- Niu bang gen (root)

Alternate botanical names

- A. major Gaertn.

- A. minus (Hill) Bernh.

- A. tomentosum Mill.

There are 18 recognised species of burdock around the world, among which five are considered as hybrid species; many are used interchangeably with A. lappa.

-

Habitat

Burdock species, native to Europe and Asia, have been naturalised throughout North America. Though regarded as weeds in the United States, they are cultivated for their edible roots in Asia. Burdock thrives along riverbanks, disturbed habitats, roadsides, vacant lots, and fields (20).

-

How to grow burdock

Burdock is an easy to grow herbaceous biennial. It can be introduced to contained areas of the garden or in pots, but steps will need to be taken to contain the plant as it successfully seeds itself in autumn. Simply remove the seed heads.

Burdock prefers loamy soil and a neutral pH in areas with average water.

Seeds should be stratified. Around 80–90% of seeds will germinate when sown directly in spring after all danger of frost has passed. Plant seeds 1/8 inch under the soil and keep evenly moist. Germination takes place in one to two weeks. Once germinated, young plants can grow quickly but it takes some time to establish a taproot of sufficient size to harvest.

Plants should be spaced at least 18 inches (46 cm.) apart. For the most part, burdock has no significant pest or disease issues and is easy to grow and maintain (22).

-

Herbal preparation of burdock

- Decoction

- Tincture

- Capsule

-

Plant parts used

Root

-

Dosage

- Tincture (1:5| 25%): Take between 2–4 ml three times a day

- Infusion/decoction: The full traditional dose is 3–18 g per day of the dried root by decoction. However, it is often wise to titrate the remedy by starting with a low dose and increasing incrementally (2,16,17).

-

Constituents

- Bitter sesquiterpene lactones: Arctiopicrin

- Lignans: Arctigenin and its glycoside arctiin, neoarctin A and B, arctignan D and E, lappaol A, C, and H

- Inulin and pectic polysaccharides

- Phytosterols: Daucosterol and B-sitosterol

- Acetylenes: Arctinones, arctinols, arctinal, arctic acids

- Caffeoylquinic, chlorogenic and hydroxycinnamic acids

- Triterpenoids

- Volatile oils

Arctigenin has strong anti-inflammatory properties in laboratory research. The seeds, more commonly used in TCM, contain higher levels of arctigenin than the root (18).

-

Burdock recipe

Let me glow burdock tea

This delicious recipe is a healing blend of chlorophyll-rich herbs that purify the blood, soothe the liver and cleanse the skin, helping you glow from the inside out. A supportive blend for anyone with pimples, acne or other skin blemishes.

Ingredients

- 3 g nettle leaf

- 2 g fennel seed

- 2 g peppermint leaf

- 2 g dandelion root

- 2 g burdock root

- 2 g red clover

- 1 g turmeric root powder

- 1 g liquorice root

- A twist of lemon juice per cup

This will serve two cups of brightening tea.

How to make burdock tea

- Put all of the ingredients in a pot (except the lemon). Add 500 ml (18 fl oz) freshly boiled filtered water.

- Leave to steep for 10–15 minutes, then strain and add the lemon.

-

Safety

Apart from occasional reports of contact dermatitis from the fresh plant, burdock has no significant safety concerns. As indicated earlier in this monograph it has quite pronounced detoxifying effects that can be associated with temporary exacerbations of dermatitis and other skin problems. These are not long-term risks and are reduced in clinical practice by combining burdock with other eliminatory remedies (3,16,17).

-

Interactions

Theoretically, burdock may increase the risk of bleeding when taken in conjunction with antiplatelet medication; however, this has not been confirmed in human clinical trials (16,17).

-

Contraindications

Burdock is not to be used where there are known allergies to plants in the Asteraceae (daisy) family.

It is contraindicated in cases of diarrhoea and/or weakness (specifically, what is known in TCM as qi deficiency) and is not recommended for treating open sores.

Pregnant women or women trying to conceive should avoid burdock (3,16,17).

-

Sustainability status of burdock

According to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Plants Status: This species is classified as ‘Least Concern’ due to its widespread distribution, stable populations and no major threats (21). Burdock grows prolifically and can spread widely due to its seed dispersal, so it is not considered a threatened plant.

Habitat loss and over-harvesting from the wild are two of the biggest threats faced by medicinal plant species. There are an increasing number of well-known herbal medicines at risk of extinction. We must, therefore, ensure that we source our medicines with sustainability in mind.

The herb supplement industry is growing at a rapid rate and until recent years a vast majority of medicinal plant produce in global trade was of unknown origin. There are some very real and urgent issues surrounding sustainability in the herb industry. These include environmental factors that affect the medicinal viability of herbs, the safety of the habitats that they are taken from, as well as the welfare of workers in the trade.

The botanical supply chain efforts for improved visibility (transparency and traceability) into verifiably sustainable production sites around the world is now certificated through the emergence of credible international voluntary sustainability standards (VSS).

Read our article on Herbal quality & safety: What to know before you buy and Sustainable sourcing of herbs to learn more about what to look for and questions to ask suppliers about sustainability.

-

Quality control

Herbal medicines are often very safe to take; however, their safety and efficacy can be jeopardised by quality issues. So, it is important to buy herbal medicines from a reputable supplier, from sources known to test their herbs to ensure there is no contamination, adulteration or substitution with incorrect plant matter, as well as ensuring that recognised marker compounds are at appropriate levels in the herbs.

Some important quality assurances to look for are certified organic labelling, the correct scientific/botanical name, and the availability of information from the supplier about ingredient origins. A supplier should be able to tell you where the herbs have come from, what contaminants are not in the herb, and what the primary compounds are.

-

References

- Bone K, Mills S. Principles and Practice of Phytotherapy: Modern Herbal Medicine. 2nd ed. Edinburgh Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier; 2013.

- Fisher C. Materia Medica of Western Herbs. Aeon Books; 2018.

- European Medicines Agency. Arctii radix . European Medicines Agency. Published September 17, 2018. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/herbal/arctii-radix

- Culpeper N. Culpeper’s Complete Herbal : Over 400 Herbs and Their Uses. Arcturus Publishing Limited; 2019.

- Mohammad S, Thiemermann C. Role of Metabolic Endotoxemia in Systemic Inflammation and Potential Interventions. Frontiers in Immunology. 2021;11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.594150

- Bensky D, Gamble A, Kaptchuk D. Chinese Herbal Medicine : Materia Medica. Eastland; 1993.

- Cancer Research UK. Essiac. www.cancerresearchuk.org. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/treatment/complementary-alternative-therapies/individual-therapies/essiac

- British Herbal Medicine Association (BHMA). A Guide to Traditional Herbal Remedies . BHMA Publications; 2003.

- Mo L, Ma K, Li Y, Song J, Song Q, Wang L. Dietary fiber from burdock root ameliorates functional constipation in aging rats by regulating intestinal motility. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2025;12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2025.1550880

- Tousch D, Bidel LucPR, Cazals G, et al. Chemical Analysis and Antihyperglycemic Activity of an Original Extract from Burdock Root (Arctium lappa). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2014;62(31):7738-7745. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf500926v

- Wu KC, Weng HK, Hsu YS, Huang PJ, Wang YK. Aqueous extract of Arctium lappa L. root (burdock) enhances chondrogenesis in human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. BMC complementary medicine and therapies. 2020;20(1):364. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-020-03158-1

- Mizuki A, Tatemichi M, Nakazawa A, Tsukada N, Nagata H, Kinoshita Y. Effects of Burdock tea on recurrence of colonic diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding: An open-labelled randomized clinical trial. Scientific Reports. 2019;9(1):6793. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43236-0

- Maghsoumi-Norouzabad L, Alipoor B, Abed R, Eftekhar Sadat B, Mesgari-Abbasi M, Asghari Jafarabadi M. Effects ofArctium lappaL. (Burdock) root tea on inflammatory status and oxidative stress in patients with knee osteoarthritis. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases. 2014;19(3):255-261. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185x.12477

- Chan YS, Cheng LN, Wu JH, et al. A review of the pharmacological effects of Arctium lappa (burdock). Inflammopharmacology. 2010;19(5):245-254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-010-0062-4

- Elliston Allen D, Hatfield G. Medicinal Plants in Folk Tradition : An Ethnobotany of Britain & Ireland. Timber Press; 2012.

- Thomsen M. Phytotherapy Desk Reference. 6th ed. Aeon Books; 2022.

- Hoffmann D. Medical Herbalism : The Science and Practice of Herbal Medicine. Healing Arts Press; 2003.

- Natural Medicines Database. Burdock. naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Published 2024. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/databases/food

- Gao Q, Yang M, Zuo Z. Overview of the anti-inflammatory effects, pharmacokinetic properties and clinical efficacies of arctigenin and arctiin from Arctium lappa L. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2018;39(5):787-801. https://doi.org/10.1038/aps.2018.32

- NatureSpot. Greater Burdock | NatureSpot. Naturespot.org. Published 2024. Accessed June 13, 2025. https://www.naturespot.org/species/greater-burdock

- Royal Botanical Gardens Kew. Arctium lappa L. | Plants of the World Online | Kew Science. Plants of the World Online. Published 2025. https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:178385-1

- Khela S. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Arctium lappa. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Published July 5, 2012. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/202931/2758087

- Urban Farmer. Burdock : From Seeds To Harvest – Urban Farmer Seeds. Ufseeds.com. Published 2023. Accessed June 13, 2025. https://www.ufseeds.com/burdock-seed-to-harvest.html?srsltid=AfmBOoo9JDzXJEizEKkoDNwGlt-MFtUPUbUiqEfKv6dfuuOSyiT-nkBx