-

Herb overview

Safety

Generally well tolerated. Occasional mild nausea, headache, gastrointestinal disturbances.

Sustainability

Least concern

FairWild certified sources availableKey constituents

Essential oils

Flavonoids

Iridoid glycosidesQuality

Mediterranean

Widely cultivated

Risk of substitution with other Vitex speciesKey actions

Antiandrogenic

HPO regulator

Phytoprogesteronic

EmmenagogeKey indications

Dysmenorrhea

PMS

PCOS

AmenorrheaKey energetics

Hot

Bitter

DryingPreperation and dosage

Berries

200–500 mg/per day

20–60 gtt of 1:2 tincture daily

-

How does it feel?

The most striking feature of agnus castus in its habitat is the powerful and very evocative pungent, warm, heavy scent that emanates from the trees in the hot sun, and which is also released when crushing the fruits in your hands.

Upon tasting, agnus castus delivers a powerful kick. There is an initial hot, peppery flavour, followed by a bitter taste that persists for some minutes and a subtle transient sweetness. The peppery flavour leaves a tingle on the tongue for a few hours following ingestion.

Agnus castus comes across as a strong sensory agent, suggesting its potency which is perhaps reflective of the relatively low doses used in clinical practice. In ancient traditions, it is considered ‘drying’, appropriate to damp conditions as characterised by congestive states including fluid retention.

-

Into the heart of agnus castus

Agnus castus (Vitex agnus-castus) Energetically, agnus castus is considered warming and drying and, therefore, can be applied to damp or cool conditions, including fluid retention.

Agnus castus has long been regarded as a woman’s remedy, and many of its traditional uses are now confirmed through modern research. It is indicated in a variety of menstrual disorders including PMS, premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), fibroids, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), endometriosis, ovarian cysts and menopausal symptoms (1,4). It is an hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) regulator and is also progesteronic, helping to increase fertility, regulate menstruation and reduce premenstrual symptoms (1,5). Agnus castus has also been shown to improve libido and sexual function in women, especially when this is related to hormonal imbalances (6).

Through supporting progesterone production, agnus castus can indirectly support the balance of oestrogen and can help to reduce oestrogen excess and associated symptoms including irregular menstruation, mood swings and fluid retention (1,7).

As a result of its effect on prolactin secretion, in low doses agnus castus has been shown to increase prolactin levels and promote milk supply acting as a galactagogue; whereas in higher doses it has been shown to decrease prolactin levels and reduce oversupply of breast milk (1). This demonstrates the importance of dose when considering the desired effect of the plant.

Agnus castus also has anti-androgenic actions and can help to reduce excess androgen hormones in patients with PCOS (8).

It has a mood-balancing and nervine action, helping to regulate mood swings especially when they are exacerbated by hormonal fluctuations during menstruation and menopause (1,5).

It is worth reflecting on the notion of a women’s remedy. Women have historically been the healers, for themselves, their children and wider community. The ‘wise woman’ is more than a turn of phrase. Women chose the remedies that women needed, and they valued and shared those that worked. From time to time, exceptional ones emerge into the wider materia medica across a whole culture — shatavari in India, dong quai in China, and helonias root in North America (unfortunately now a threatened species and no longer recommended). In southern Europe, that women’s remedy is agnus castus.

-

What practitioners say

Reproductive system

Reproductive systemAgnus castus is a favoured reproductive remedy amongst Western medical herbalists. It is used in a wide range of menstrual and also perimenopausal indications, now with increasing focus on conditions of high prolactin levels and progesterone deficiency (e.g., cystic hyperplasia of the endometrium). These include PMS , especially with fluid retention and breast swelling, and other premenstrually-aggravated symptoms, like sleeplessness and mood changes (1).

Agnus castus has demonstrated an ability to regulate disturbed menstrual cycles and periods, including lengthened or shortened cycles, and loss of periods (where pregnancy and other medical conditions have been ruled out). Here, its effects seem to be greater where the menstrual disturbances are linked to corpus luteum deficiency — i.e. when the corpus luteum doesn’t produce enough progesterone during the luteal phase (17). . Ovulation tracking using daily temperature checks, cycle tracking and mucus testing can be useful in identifying menstrual disturbances.

Agnus castus has been shown to reduce cases of bleeding between periods (metrorrhagia) as a result of IUD (17). Further reproductive indications for this herb include PCOS, alongside other remedies to manage the insulin resistance element of this condition, such as barberry (Berberis vulgaris)or gymnema (Gymnema sylvestre). It can also provide symptomatic relief for endometriosis and fibroids. Stress is a contributing factor to raised prolactin levels, which also indicates agnus castus due to its calming nervine action (17).

Infertility is also a traditional indication for agnus castus. In this case, it is most appropriate if there are problems with conception linked to disrupted menstrual cycles; for example, anovulation or issues with implantation.As women go through the menopause they may find that premenstrual patterns merge into a wider and longer sometimes congestive pattern, as though the PMS is taking over. This would be an instance to consider agnus castus as part of a treatment protocol (11).

Through its dopaminergic action, agnus castus can inhibit prolactin secretion which is helpful in treating hyperprolactinaemia and in cases where prolactin is elevated — for example,pituitary tumours (2).

Skin

Agnus castus can help to manage acne as an internal remedy, as it can help to regulate hormones that contribute to acne exacerbations, which is particularly found in individuals with PCOS (1,4).

-

Agnus castus research

Agnus castus (Vitex agnus-castus) Chaste tree (Vitex agnus-castus): Pharmacology and clinical indications

The research evidence suggests that agnus castus inhibits the hormone prolactin via dopaminergic activity in the anterior pituitary. A decrease of prolactin will affect the levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), oestrogen in women and testosterone in men. In terms of the menstrual cycle this has the effect of enhancing corpus luteal development (thereby correcting a relative progesterone deficiency) normalising the menstrual cycle, and encouraging ovulation (18).

Vitex agnus-castus extracts for female reproductive disorders: A systematic review of clinical trials

A systematic review analysed twelve randomised controlled trials (RCT) on agnus castus for reproductive conditions. One trial found agnus castus to be superior to placebo for reducing TRH-stimulated prolactin levels and increasing progesterone, thereby regulating the menstrual cycle. A further RCT showed agnus castus to be comparable to bromocriptine in reducing serum prolactin and improving cyclic mastalgia. The mechanism of action was found to be dopaminergic, and by agnus castus interacting with the D2 receptors in the anterior pituitary gland (19).

Vitex agnus castus for the treatment of cyclic mastalgia: A systematic review and meta-analysis

A meta-analysis and systematic review of 25 clinical trials was carried out to evaluate the effect of agnus castus on cyclic mastalgia in women aged between 18 and 45. The typical dosage was between 20–40 mg per day over a period of three months. Results showed agnus castus was significantly more effective than placebo in reducing breast pain in six RCTs and it also reduced serum prolactin levels (20).

Polycystic ovaries and herbal remedies: A systematic review

This review examined studies published between 1990 to 2021 on medicinal plants in the treatment of PCOS. The review found that agnus castus reduced hirsutism by lowering levels of testosterone and androgens (21).

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

-

What can I use agnus castus for?

Agnus castus (Vitex agnus-castus) This ancient Mediterranean female reproductive remedy has become more familiar in modern herbalism, and is particularly well known in Germany, where it was popularised early in the 20th century. Its predominant application is in relieving symptoms of tension occurring either before a period or during perimenopause. However, it has been used for a range of gynaecological conditions, including premenstrual syndrome (PMS), irregular menstruation, fluid retention, swollen breasts and to facilitate fertility through hormonal regulation (1).

Agnus castus has a dopaminergic action on the anterior pituitary gland and mimics dopamine, which is the key inhibitor of prolactin. It, therefore, helps to reduce high prolactin levels, which are responsible for a range of hormonal symptoms, including menstrual irregularities and swollen breasts (1,2). Agnus castus has also been used successfully in treating acne, especially when it’s caused by hormonal fluctuations (3).

Agnus castus is regarded as a nervine owing to its relaxing and calming qualities. It is often included in preparations for people suffering from premenstrual and perimenopausal anxiety and low mood (4).

-

Did you know?

Agnus castus (Vitex agnus-castus) In ancient Greece, the tree was called agnos, meaning holy, pure and chaste. They dedicated it to their mother goddess Demeter. At the festival of Thesmophoria held in her honour, Greek women, who aimed to remain chaste for the occasion, strewed their beds with branches of the tree, and wore garlands of it in the day, so that the aroma might subdue the ardour of any would-be suitor (22).

The ancient Romans dedicated the vitex tree to the goddess Hera, the protector of motherhood and marriage, who was said to have been born under one. Roman wives were also said to use the leaves to reduce the libido of their husbands. Vestal virgins carried twigs of the tree as a symbol of chastity).

Another common name for agnus castus is ‘monk’s pepper’. As well as referring to its peppery taste, this was said to support its reputation for suppressing “the lusts of the flesh” in monastic institutions (22).

-

Botanical description

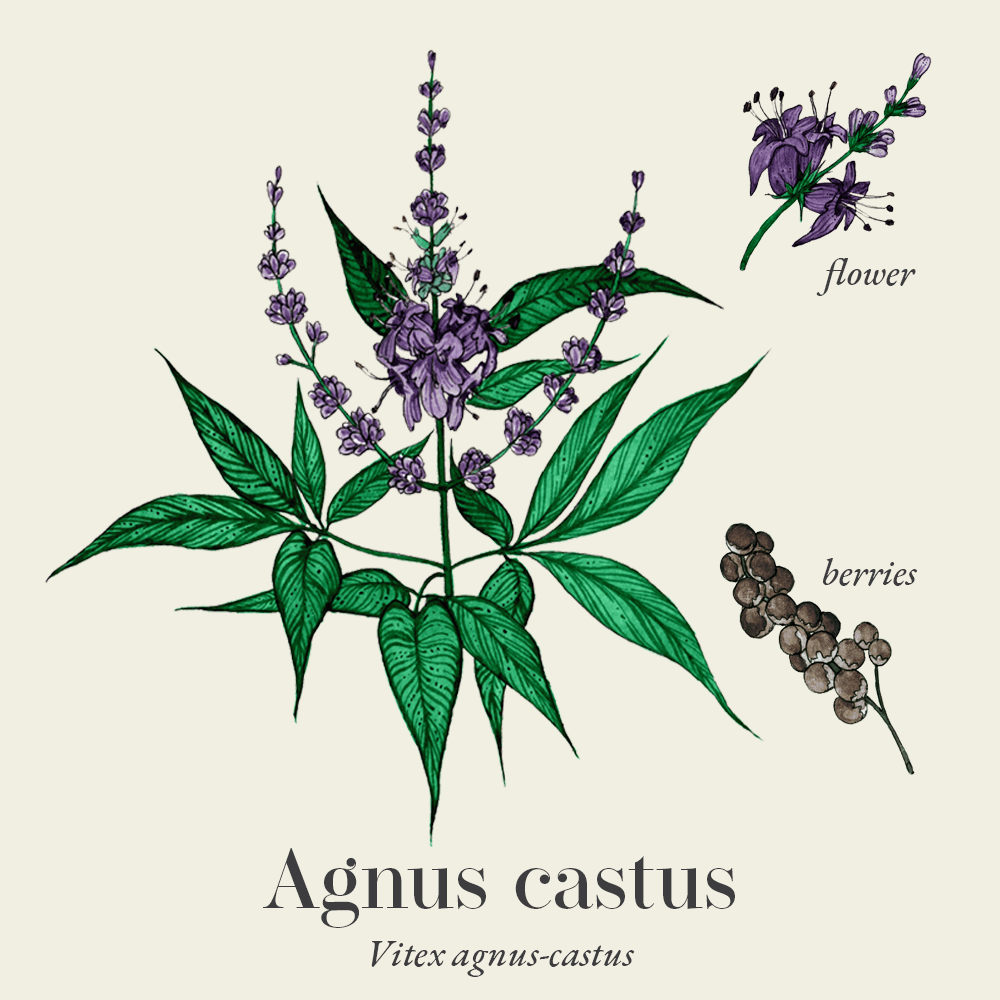

Agnus castus or chasteberry is the fruit (drupe) of a shrubby plant, which grows to 3–5 m in height producing large dark green leaves radiating from a long, hairy stalk.

The shoots terminate in a slender spike and are composed of whorls of violet flowers. The black spherical berries are lignified ovaries of two carpels each containing one seed, roughly ovoid about three by four millimetres, dark-grey in colour, yielding when crushed a dark powder of characteristic aroma and fragrant, slightly acrid and bitter peppery taste (25).

-

Common names

- Chasteberry

- Chaste tree

- Monk’s pepper (Eng)

- Keuschlammfrüchte (Ger)

- Schäffmülle (Ger)

- Agneau chaste (Fr)

- Arbre au poivre (Fr)

- Gatillier (Fr)

-

Habitat

Native of the Mediterranean region and Central Asia. It is one of the few temperate-zone species of Vitex, which is on the whole a genus of tropical and sub-tropical flowering plants.

-

How to grow agnus castus

Agnus cactus prefers a well-drained soil in full sun. Soil types: loam, chalk or sandy soils. In frost-prone areas with shelter from the cold and from drying winds. Best grown near a south or west-facing wall. Vitex will grow well in a sunny garden flower bed or border.

-

Herbal preparation of agnus castus

- Tincture

- Dried

- Capsule

- Liquid extract

-

Plant parts used

Fruit (berries)

-

Dosage

Often used for a maximum of 3–6 months and then reviewed with the practitioner.

Dried / Capsule

Between 200–500 mg per day for most purposes, increasing to 2.5 g for short term use, e.g., for acne. In more severe cases, a higher dose is often prescribed— ranging between 1000–2500 mg per day on a short term basis (1,23).

Tincture (1:5 | 25%)

1–5 ml (20–60 drops) in a little water per day (1,24). Correct dosage is important with regard to agnus castus as in low doses, it increases prolactin levels, and in higher doses it decreases them. Some practitioners will recommend taking agnus castus during the first half of the menstrual as a separate mix on its own, whilst others will include vitex in a herbal formulation to support throughout the month (1,24). A good rule of thumb is to start on a low dose and increase accordingly, if necessary.

Infusion

One tsp of dried berries, infused for 10–15 minutes in a cup of boiling water, strained and drank three times a day (1,24).

-

Constituents

- Essential oil: Up to 0.7%, containing monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes, such as limonene, sabinene, 1,8-cineole (eucalyptol), beta-caryophyllene and trans-beta-farnesene

- Flavonoids: Vitexin and orientin and methoxylated flavones casticin, eupatorin and penduletin

- Iridoid glycosides: Aucubin and agnuside

- Diterpenes: Labdane and halimane types (clerodadienols) including rotundifuran, vitexilactone, vitetrifolin B and C, and viteagnusins A to I

The diterpenes bind to dopamine D2 receptors in the anterior pituitary and appear to be the constituents responsible for decreasing serum prolactin. The flavone casticin may also contribute to this effect (17).

-

Agnus castus recipe

Premenstrual mood support tea

This recipe can be made during the luteal phase in the lead up to menstruation to support emotional changes and fluctuations in mood. This tea is designed to provide balance and support for symptoms of PMS including stress, anger or anxiety.

Ingredients

- 1 tsp agnus castus berries

- 1 tbsp dried rose petals

- 0.5 tsp dried motherwort

- 1 tsp dried ceylon cinnamon

- 2 cardamom pods

- Teapot

- Filtered boiled water

How to make an agnus castus tea

- Crush the cardamom pods to release the volatile oils and grind the agnus castus berries.

- Boil the kettle with freshly filtered water

- Place all the ingredients in a teaspot and cover with the boiling water

- Steep for five minutes

- Strain and drink up to three cups a day

-

Safety

In general, agnus castus is well tolerated. Occasional mild and reversible nausea, headache, gastrointestinal disturbances, menstrual disorders, acne, pruritus, and erythematous rash have been reported in large studies (13). Among 352 nursing mothers given agnus cactus tincture, 15 cases of skin problems and some cases of early menstrual period occurred (14).

-

Interactions

Avoid in conjunction with HRT, progesterone drugs and OCP and caution is advised alongside contraceptive medication (5,24).

-

Contraindications

Caution is advised with individuals with oestrogen and progesterone sensitive tumours (5).

-

Sustainability status of agnus castus

NatureServe database states that in relation to endangered status this plant is unranked. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species database states an assessment was made in 2012 on global prevalence of Vitex agnus-castus in the wild, with the results listing the plant as ‘data deficient’ (27,28).

Habitat loss and over-harvesting from the wild are two of the biggest threats faced by medicinal plant species. There are an increasing number of well-known herbal medicines at risk of extinction. We must, therefore, ensure that we source our medicines with sustainability in mind.

The herb supplement industry is growing at a rapid rate and until recent years a vast majority of medicinal plant produce in global trade was of unknown origin. There are some very real and urgent issues surrounding sustainability in the herb industry. These include environmental factors that affect the medicinal viability of herbs, the safety of the habitats that they are taken from, as well as the welfare of workers in the trade.

The botanical supply chain efforts for improved visibility (transparency and traceability) into verifiably sustainable production sites around the world is now certificated through the emergence of credible international voluntary sustainability standards (VSS).

Read our article on Herbal quality & safety: What to know before you buy and Sustainable sourcing of herbs to learn more about what to look for and questions to ask suppliers about sustainability.

-

Quality control

Herbal medicines are often very safe to take; however, their safety and efficacy can be jeopardised by quality issues. So, it is important to buy herbal medicines from a reputable supplier, from sources known to test their herbs to ensure there is no contamination, adulteration or substitution with incorrect plant matter, as well as ensuring that recognised marker compounds are at appropriate levels in the herbs.

Some important quality assurances to look for are certified organic labelling, the correct scientific/botanical name, and the availability of information from the supplier about ingredient origins. A supplier should be able to tell you where the herbs have come from, what contaminants are not in the herb, and what the primary compounds are.

-

References

- Bone K, Mills S. Principles and Practice of Phytotherapy: Modern Herbal Medicine. 2nd ed. Edinburgh Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier; 2013.

- Puglia L, Lowry JV, Tamagno G. Vitex agnus castus effects on hyperprolactinaemia. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2023;14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1269781

- Nasri H, Bahmani M, Shahinfard N, Moradi Nafchi A, Saberianpour S, Rafieian Kopaei M. Medicinal Plants for the Treatment of Acne Vulgaris: A Review of Recent Evidences. Jundishapur Journal of Microbiology. 2015;8(11). https://doi.org/10.5812/jjm.25580

- Mcintyre A. Complete Herbal Tutor: The Definitive Guide to the Principles and Practices of Herbal Medicine (Second Edition). Aeon Books Limited; 2019.

- Thomsen M. Phytotherapy Desk Reference. 6th ed. Aeon Books; 2022.

- Shaw S, Wyatt K, Campbell J, Ernst E, Thompson-Coon J. Vitex agnus castus for premenstrual syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Published online March 2, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd004632.pub2

- Feyzollahi Z, Mohseni Kouchesfehani H, Jalali H, Eslimi-Esfahani D, Hosseini AS. Effect of Vitex agnus-castus ethanolic extract on hypothalamic KISS-1 gene expression in a rat model of polycystic ovary syndrome. Avicenna Journal of Phytomedicine. 2021;11(3):292. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8140208/

- National Centre for Complementary and Integrative Health. Chasteberry. NCCIH. Published July 2020. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/chasteberry

- Dioscorides P. De Materia Medica. Osbaldeston TA, Wood RPA, trans. Johannesburg, South Africa: Ibidis Press; 2000.

- Grieve M. A Modern Herbal. Vol 1. London, UK: Jonathan Cape; 1931.

- Hoffmann D. Medical Herbalism: The Science and Practice of Herbal Medicine. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press; 2003.

- Parkinson J. Theatrum Botanicum: The Theater of Plants. London, UK: Tho. Cotes; 1640.

- Galen. On the Temperaments of Simple Drugs. In: Kühn CG, ed. Claudii Galeni Opera Omnia. Vol 11. Leipzig, Germany: Knobloch; 1826.

- King J. The American Eclectic Dispensatory. Cincinnati, OH: Moore, Wilstach & Baldwin; 1866.

- Felter HW, Lloyd JU. King’s American Dispensatory. 18th ed. Cincinnati, OH: Ohio Valley Co; 1898.

- Ellingwood F. American Materia Medica, Therapeutics and Pharmacognosy. Chicago, IL: Ellingwood’s Therapeutist; 1919.

- Yavarikia P, Shahnazi M, Hadavand Mirzaie S, Javadzadeh Y, Lutfi R. Comparing the effect of mefenamic Acid and vitex agnus on intrauterine device induced bleeding. Journal of caring sciences. 2013;2(3):245-254. https://doi.org/10.5681/jcs.2013.030

- Wuttke W, Jarry H, Christoffel V, Spengler B, Seidlová-Wuttke D. Chaste tree (Vitex agnus-castus) – Pharmacology and clinical indications. Phytomedicine. 2003;10(4):348-357. https://doi.org/10.1078/094471103322004866

- Van Die M, Burger H, Teede H, Bone K. Vitex agnus-castus Extracts for Female Reproductive Disorders: A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials. Planta Medica. 2012;79(07):562-575. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0032-1327831

- Ooi SL, Watts S, McClean R, Pak SC. Vitex Agnus-Castus for the Treatment of Cyclic Mastalgia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Women’s Health (2002). 2020;29(2):262-278. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2019.7770

- Manouchehri A, Abbaszadeh S, Ahmadi M, Nejad FK, Bahmani M, Dastyar N. Polycystic ovaries and herbal remedies: A systematic review. JBRA Assist Reprod. 2023;27(1):85-91. Published 2023 Mar 30. https://doi.org/10.5935/1518-0557.20220024

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Chasteberry. PubMed. Published 2006. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501807/

- Natural Medicines Database. Vitex Agnus Castus. naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Published 2024. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/databases/food

- Fisher C. Materia Medica of Western Herbs. Aeon Books; 2018.

- RHS. Vitex agnus-castus | chaste tree Shrubs/RHS Gardening. Published 2025. https://www.rhs.org.uk/plants/43844/vitex-agnus-castus/details

- Royal Botanical Gardens Kew. Vitex agnus-castus L. | Plants of the World Online | Kew Science. Plants of the World Online. Published 2025. https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:865568-1

- Nature Serve Explorer. Vitex Agnus Castus. Natureserve.org. Published 2025. Accessed June 11, 2025. https://explorer.natureserve.org/Taxon/ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.130830/Vitex_agnus-castus

- Wilson B, Khela S. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Vitex agnus-castus. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Published October 3, 2017. Accessed June 11, 2025. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/203350/177441757