-

Herb overview

Safety

Milk thistle is generally safe and well tolerated

Sustainability

Lower risk

Key constituents

Flavolignans: Silymarin (consisting of silybin A and B)

FlavonoidsQuality

Native to Europe, N. America and W. Asia

Mostly cultivated

Inaccurate silymarin content claimsKey actions

Hepatic

Hepatoprotective

Anti-inflammatory

AntioxidantKey indications

Gall stones

Dyspepsia

Liver disease

ToxicityKey energetics

Cool

Moist

SweetPreperation and dosage

Seed

4–9 g dried seed daily, decocted

Tincture (1:5 | 25%): 6–12 ml daily

-

How does it feel?

Milk thistle seed has a mild, nutty and slightly sweet taste with a subtle undertone of bitterness.

Milk thistle is a refreshingly sweet and aromatic medicine that is much easier to tolerate than the usual bitter liver herbs. It works best as an alcoholic extract, powdered or dried seed preparation.

-

Into the heart of milk thistle

Milk thistle has a sweet, warming and nourishing action. Due to its milder bitter flavour, it is useful for those with a colder constitution or for people who are depleted and require nourishing restorative support alongside detoxification. Milk thistle’s warming energetics also have a decongestant effect on stuck and stagnant blood flow resulting from its ability to reduce and eliminate toxicity from the blood (1).

Matthew Wood recommends it for people with dry constipation related to liver congestion and lack of bile. This type of constipation will usually present as hard and small stools (rabbit droppings) or they may also be pale in colour due to lack of bile. They might also float rather than sink, which can indicate poor fat absorption (4).

-

What practitioners say

Milk thistle in a bowl (Silybum marianum) Digestive system

Some of the primary uses for milk thistle are centred around the digestive system with a focus on the liver and gallbladder. Herbalists may use milk thistle as a part of a supportive treatment for all manner of liver diseases including for cirrhosis, fatty liver, hepatitis and other liver function abnormalities (1). Milk thistle is also indicated for liver problems that may occur in relation to medicines, chemical exposure or environmental pollutants (1).

A number of mechanisms have been identified as being involved in milk thistle’s effects on the liver. The active constituent silymarin works by stabilising and protecting the hepatocyte membrane against injury, as well as regulating its permeability (1). It has also been shown to increase the proliferation of liver cells Kupffer cells, which phagocytose pathogens, bacteria and other foreign material from the blood (6). Milk thistle’s antioxidant action acts by increasing enzymes (superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase) in liver cells to protect them from oxidative stress induced by drugs, alcohol, toxins or other pollutants (7).

Endocrine system

Milk thistle has potent free radical scavenging properties. It is used to improve detoxification mechanisms and improve cellular regeneration (1). Milk thistle is also indicated in a number of conditions that are caused by oxidative stress and where there has been exposure to pollutants, chemicals and other toxins such as liver or cardiovascular diseases (8).

Milk thistle may also be applied for the treatment and prevention of blood glucose dysregulation, that manifests as diabetes. It may be most relevant for use where liver conditions are accompanied by a diabetic predisposition, or to help lower blood glucose levels in type 2 diabetic patients alongside conventional treatment (9). Silymarin has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity, support glucose metabolism, and reduce oxidative stress and inflammation in pancreatic beta cells (9).

Milk thistle can be used to support phase 1 and phase 2 detoxification pathways through its antioxidant, cell membrane stabilisation, protein synthesis and bile production actions The phase 1 pathway attempts to break down compounds for excretion via oxidation, hydrolysis or reduction reactions facilitated by the cytochrome P450 enzyme system. If that doesn’t work, the compounds go into phase 2 where other molecules (such as cysteine, glutathione, or sulphur) are added to make the initial compound suitable for excretion. It is then excreted through the bile into the bowel or eliminated as water-soluble compounds via the kidneys and bladder (7).

Immune system

Milk thistle and its main constituent silymarin have been shown to modulate immune system activity. They enhance lymphocyte proliferation and increase levels of cytokines, such as interferon gamma, IL-4, and IL-10, helping to regulate the immune response and fight infection (10). This immune modulation action can be beneficial in treating autoimmune conditions and liver conditions with an immunological component.

Silybin and silymarin have been shown to exhibit antimicrobial activity against gram-positive bacteria and increase the effect of resistant S.aureus to antibiotics (5,10).

Reproductive system

Milk thistle is a galactagogue and has traditionally, and is still now used to promote breast milk in breastfeeding mothers (1,4).

-

Milk thistle research

Milk thistle seeds (Silybum marianum) There are several high-quality clinical trials on milk thistle. Most studies have investigated the isolated compound silymarin or its most active isomer silybin, rather than the plant part in its whole form. A number of these studies have been included below to demonstrate the evidence base for the medicinal actions discussed in this monograph.

Most studies have been carried out on extracts that contain between 60–80% silymarin (1). Many trials using the standardised extract of milk thistle support the clinical indications for both non-alcoholic and alcoholic fatty liver disease/damage as well as for cirrhosis, fatty liver, exposure to chemical pollutants (such as drugs, halogenated hydrocarbons, solvents, paints, glues and anaesthesia) and even for the treatment of death cap poisoning (1).

An updated systematic review with meta-analysis for the clinical evidence of silymarin

In this review, 65 papers were analysed and confirmed silymarin to have a number of effects, such as anticancer, antidiabetic, and cardioprotective properties. Milk thistle also has a strong body of evidence for mechanisms by which it protects the liver against toxins as well as for its ability to therapeutically assist in chronic liver diseases (11).

Silibinin as a major component of milk thistle seed provides promising influences against diabetes and its complications: A systematic review

This review covered all databases from time of inception to 2024 to explore the effects of silibinin on diabetes and its varied complications. Silibinin was found to improve conditions by multiple mechanisms of action including by reducing insulin resistance and lowering reactive oxygen species. It was also found to improve triglyceride levels, cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein (LDL levels. The review concluded that silybinin provided promising anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antidiabetic and insulin sensitising actions and would be a great support for diabetic conditions (12).

Silymarin as an antioxidant therapy in chronic liver diseases: A comprehensive review

This study examined silymarin and its role as an antioxidant for chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Silymarin was found to have hepatoprotective properties by scavenging free radical enzymes, reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines, stabilising cell membranes and promoting liver cell regeneration. It was also found to reduce elevated liver enzymes (ALT, AST) and reduce the progression of fibrosis in NAFLD and alcoholic liver disease (ALD). The doses varied between 140 mg to 700 mg daily depending on the severity of the condition (12).

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

-

What can I use milk thistle for?

Milk thistle (Silybum marianum) Milk thistle is well known as a liver and gallbladder tonic that is generally safe for all to use. It works via a direct stimulating effect on the liver, which also encourages the flow of bile. Milk thistle offers both restorative and protective actions on the liver. It encourages optimum function of the liver and gall bladder — offering a wide range of therapeutic benefits, such as better detoxification of the blood as well as improving the assimilation of fat-soluble nutrients (1).

Milk thistle’s protective and rejuvenating effect on liver cells has been well documented in modern research. This includes cases in which the liver has been exposed to high levels of chemicals and pollution, whether through diet, medication or unprotected contact (2).

As the name alludes in the Doctrine of Signatures — the concept that plants may allude tor their therapeutic uses through their appearance or growing environment —, milk thistle is used as a galactagogue, to enhance the flow of breast milk and care for the young. The milky white veins are a helpful sign, suggestive of its benefits.

Milk thistle is also a useful remedy for dyspepsia and digestive complaints that are associated with a sluggish liver, after serious conditions have been ruled out (2,3).

-

Did you know?

The main constituent— silymarin belongs to the polyphenol constituent group, more specifically the flavolignans. These have a protective and rejuvenating effect on liver cells and have been shown to neutralise the toxic effects of one of nature’s most poisonous mushrooms — Amanita phalloides.

This mushroom is known as the death cap mushroom, and it produces the liver-destroying alkaloids amanantine and phalloidine. These alkaloids inhibit hepatocyte function and have a mortality rate of 20%. A treatment derived from milk thistle has now been developed into an injectable form for acute poisoning (5).

-

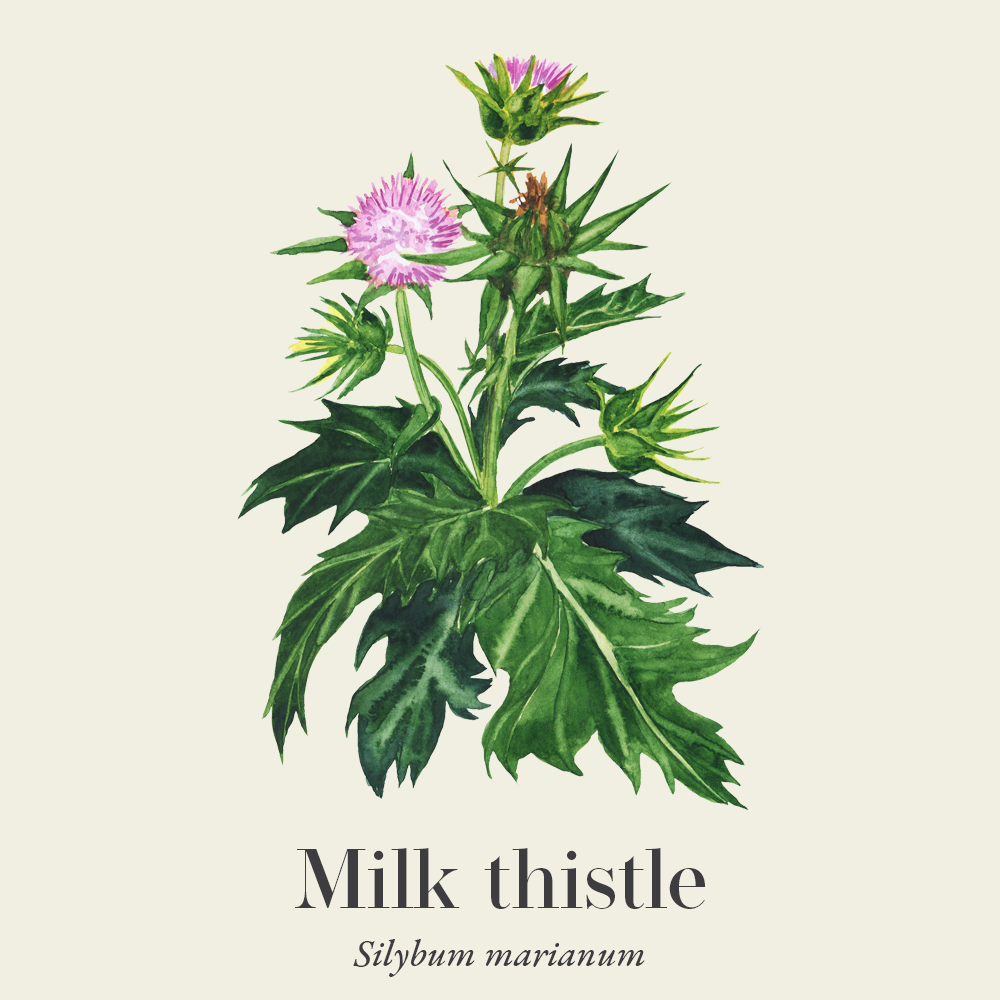

Botanical description

Milk thistle is a robust biennial thistle, forming a rosette of large, spiny dark green leaves with prominent white veins (variegated) that can be three inches across.

It has purple flower heads with spiny bracts, appearing in the second year. The bluish-purple seed head reaches four inches tall (15).

-

Common names

- Blessed thistle

- Marian thistle

- Mary thistle

- Saint Mary’s thistle

- Mediterranean milk thistle

- Variegated thistle

- Scotch thistle

-

Habitat

Milk thistle is native to the Mediterranean region and through to Central Asia, India and Ethiopia. It is mostly found in disturbed areas, such as pastures, roadsides, ditches, and fencerows (16).

-

How to grow milk thistle

Milk thistle can be grown as a winter annual or a biennial which means that it dies once it has flowered and produced seeds. However, it usually self-seeds in the vicinity, so take care to keep the plants under control.

Either sow seeds in early spring for late summer flowering, or sow in late summer for flowering in early summer the following year. Either way, as these are large seeds that germinate and grow quickly, we recommend sowing the seeds directly into pots (rather than trays) – one seed per pot.

If you sow in the spring, sow indoors and plant out as soon as they are big enough to handle. Space the plants at least 2–3 feet apart and allow plenty of space for paths (the spiky leaves will stop all traffic on your paths if you don’t). If you sow in late summer, sow outdoors and move the pots indoors for the winter, then plant out the following spring. Late summer sowing normally produces higher seed yields (24).

-

Herbal preparation of milk thistle

- Liquid extract

- Decoction

- Capsules

-

Plant parts used

Seed

-

Dosage

- Tincture (1:5 | 25%): Take between 2–4 ml three times a day (1,4).

- Fluid extract (1:1 | 25%): Take between 4–9 ml a day.

- Infusion/decoction: To make a decoction place between 4–9 g of dried seed in one cup of boiling water, simmer gently for between 15–20 minutes. This should be drunk hot daily up to three times a day.

- Capsules/ tablets: There are many readily available capsules or tablets that are standardised to contain a minimum of 200 mg silymarin. These should be employed to treat more severe cases of liver damage. For severe liver damage, high doses are recommended to optimise treatment outcomes. The availability of silymarin is enhanced by the consecutive supplementing of lecithin (1). For serious conditions like this, one should always consult a clinical herbalist (1,4).

Silybin was used at a dose of 20 mg/kg of body weight per day to treat Amanita spp. poisoning (1,4).

-

Constituents

- Flavolignans (1.5–3%): Silymarin (consisting of silybin A and silybin B), silychristin, silydianin, diastereoisomers isosilybin A and isosilybin B. A silibinin extract consists of equal parts of silybin A and silybin B. Flavolignans are at their highest in the more mature seeds.

- Flavonoids: Apigenin, taxifolin a, 3 dihydroflavonol

- Amines: Tyramine, histamine, trimethylglycine

- Polyacetylenes

- Fixed oil (20–30%)

- Oleic, linoleic, myristic, palmitic and stearic acids (1,4)

-

Milk thistle recipe

Milk thistle seasoning salt

This flavoursome and simple umami recipe can be made in batches to be added onto a variety of savoury dishes. This is a simple but effective way to regularly incorporate milk into the diet.

Ingredients

- 1 tbsp milk thistle seeds

- 1 tbsp seaweed flakes

- 1 tbsp dried nettle leaves

- 1.5 tsp celery seeds

- 5 tbsp unrefined sea salt

How to make milk thistle salt

- Place the milk thistle seeds, seaweed, nettle and celery seeds into a spice or coffee grinder and grind to preference.

- Transfer the mixture into a clean jar and add the salt.

- Mix well.

- Store the mixture in a sealed jar and add to savoury dishes throughout the day.

-

Safety

Milk thistle is generally well tolerated and is safe to use in children in appropriate doses and short term. There have been no documented issues with using milk thistle during pregnancy and breastfeeding; however, it is advised to consult with a professional medical herbalist (4,13).

-

Interactions

Milk thistle could theoretically interact with antidiabetic medication to increase the risk of hypoglycaemia (13). It may also inhibit cytochrome P450 2B6 (CYP2B6) substrates and should be used with caution in these instances (13,14). Milk thistle may also increase the clearance of certain medications including losartan and metronizadole (1,14).

-

Contraindications

Not recommended for anyone with a known sensitivity to plants in the daisy (Asteraceae family) or its constituents (1,3).

-

Sustainability status of milk thistle

Milk thistle is classified as least concern on the IUCN redlist due to stable populations in most of its native habitats and no major threats (17). Once it is established it can take over local plants and spread widely and it is both harvested in the wild and cultivated for use as a medicine (18).

Habitat loss and over-harvesting from the wild are two of the biggest threats faced by medicinal plant species. There are an increasing number of well-known herbal medicines at risk of extinction. We must, therefore, ensure that we source our medicines with sustainability in mind.

The herb supplement industry is growing at a rapid rate and until recent years a vast majority of medicinal plant produce in global trade was of unknown origin. There are some very real and urgent issues surrounding sustainability in the herb industry. These include environmental factors that affect the medicinal viability of herbs, the safety of the habitats that they are taken from, as well as the welfare of workers in the trade.

The botanical supply chain efforts for improved visibility (transparency and traceability) into verifiably sustainable production sites around the world is now certificated through the emergence of credible international voluntary sustainability standards (VSS).

Read our article on Herbal quality & safety: What to know before you buy and Sustainable sourcing of herbs to learn more about what to look for and questions to ask suppliers about sustainability.

-

Quality control

- Country of origin: Asia, Europe and North America

- How sourced: Cultivated and wild-harvested

- Risks: Adulteration with other species of Silybum and the use of synthetic colorants and depleted extracts

- Key marker compounds: Silymarin and flavonoids

Milk thistle (Silybum marianum) contains flavanolignans, flavonoids, and fixed oils based principally on linoleic and oleic acid (19). The most important bioactive constituent in milk thistle is the mixture of flavanolignans called silymarin. There are limits set for silymarin in national pharmacopoeias, for example, the British Pharmacopeia (BP) and United States Pharmacopeia (USP) specify a minimum content of 1.5% for silymarin (20).

There are many studies that have highlighted concerns regarding the quality of commercially available milk thistle products (21,22,23. Research shows that between 30–50% of commercially traded milk thistle products do not meet their labelling claim for silymarin content (21). Products were found to have either a lower content than claimed or in some cases no silymarin at all (22). If we examine the value chain, the majority of commercial milk thistle supply is produced under cultivation, and so the risk of accidental adulteration is very low. If it was wild collected, there will be some risks as distinguishing between the species S. marianum and S. eburneum based on morphological characteristics can be very challenging (21).

The primary cause of milk thistle quality concerns is down to the extract ingredient supply, and this is well documented in research (21). There are several reasons that could explain the high incidence in the mislabelling of milk thistle products. The traditional method of analysis is through the spectrophotometric method, which is still widely used today; however, it has less specificity than the newer HPLC-UV methods, which could account for some differences in levels of silymarin found (21).

However, it would not explain why in some products no silymarin was detected. Other practices that have been documented include the use of depleted milk thistle extracts, which are cheap and are of poor quality, so this is clearly an example of economically-motivated adulteration. The use of synthetic colorants was also documented and these are used to give the appearance of compliance when using the spectrophotometric methods (21). It is, therefore, important to ensure that you are buying from suppliers who understand their supply chain and manage these adulteration risks.

-

References

- Bone K, Mills S. Principles and Practice of Phytotherapy: Modern Herbal Medicine. 2nd ed. Edinburgh Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier; 2013.

- George T, Patel RK. Milk Thistle. Nih.gov. Published September 3, 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541075/

- Thomsen M. Phytotherapy Desk Reference. 6th ed. Aeon Books; 2022.

- Wood M. The Earthwise Herbal : A Complete Guide to Old World Medicinal Plants. North Atlantic Books; 2008.

- Fisher C. Materia Medica of Western Herbs. Aeon Books; 2018.

- Basit H, Tan ML, Webster DR. Histology, Kupffer Cell. PubMed. Published 2020. Accessed April 2, 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493226/

- Mulrow C, Lawrence V, Jacobs B, et al. Milk Thistle: Effects on Liver Disease and Cirrhosis and Clinical Adverse Effects: Summary. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2000. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11896/

- Taleb A, Ahmad KA, Ihsan AU, et al. Antioxidant effects and mechanism of silymarin in oxidative stress induced cardiovascular diseases. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2018;102:689-698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2018.03.140

- Kazazis CE, Evangelopoulos AA, Kollas A, Vallianou NG. The Therapeutic Potential of Milk Thistle in Diabetes. The Review of Diabetic Studies. 2014;11(2):167-174. https://doi.org/10.1900/rds.2014.11.167

- Wilasrusmee C, Kittur S, Shah G, et al. Immunostimulatory effect of Silybum Marianum (milk thistle) extract. Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research. 2002;8(11):BR439-443. Accessed July 5, 2024. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12444368/

- Saller R, Brignoli R, Melzer J, Meier R. An Updated Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis for the Clinical Evidence of Silymarin. Forschende Komplementärmedizin / Research in Complementary Medicine. 2008;15(1):9-20. https://doi.org/10.1159/000113648

- Parisa Zare Mehrjerdi, Asadi S, Ehsani E, Askari VR, Rahimi VB. Silibinin as a major component of milk thistle seed provides promising influences against diabetes and its complications: a systematic review. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg s Archives of Pharmacology. 2024;397(10):7531-7549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00210-024-03172-x

- Natural Medicines Database. Milk thistle. Therapeuticresearch.com. Published 2025. Accessed August 23, 2025. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/Data/ProMonographs/Milk-Thistle#safety

- Williamson E, Driver S, Baxter K, Al E. Stockley’s Herbal Medicines Interactions : A Guide to the Interactions of Herbal Medicines, Dietary Supplements and Nutraceuticals with Conventional Medicines. Pharmaceutical Press; 2009.

- Karkanis A, Bilalis D, Efthimiadou A. Cultivation of milk thistle (Silybum marianum L. Gaertn.), a medicinal weed. Industrial Crops and Products. 2011;34(1):825-830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2011.03.027

- Royal Botanical Gardens Kew. Silybum marianum (L.) Gaertn. | Plants of the World Online | Kew Science. Plants of the World Online. Published 2025. Accessed July 21, 2023. https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:249211-1

- RBG R, Khela S. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Silybum marianum. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Published August 28, 2019. Accessed August 23, 2025. https://www.iucnredlist.org/fr/species/202991/88329022

- Samanek J, Org B. BCINVASIVES.CA / INFO@BCINVASIVES.CA / 1-888-933-3722.; 2023. https://bcinvasives.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/Milk-thistle-Dec-2023-post-for-public-input.pdf

- Ancuța Cristina Raclariu-Manolică, Socaciu C. Detecting and Profiling of Milk Thistle Metabolites in Food Supplements: A Safety-Oriented Approach by Advanced Analytics. Metabolites. 2023;13(3):440-440. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo13030440

- British Pharmacopoeia Commission. British Pharmacopoeia 2025. London TSO; 2025.

- McCutcheon A. Adulteration of milk thistle (Silybum marianum). Botanical Adulterants Prevention Bulletin. Botanical Adulterants Prevention Program. Published online 2020.

- BBC. Episode 1 – Do herbal supplements contain what they say on the label? BBC. Published July 15, 2015. Accessed August 23, 2025. http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/4hX30rMYkMv9YjMTH38MY6/do-herbal-supplements-contain-what-they-say-on-the-label.

- Booker A, Heinrich M. Value Chains of Botanical and Herbal Medicinal Products: A European Perspective. Published online November 30, 2016.

- RHS. Silybum marianum | milk thistle Annual Biennial/RHS Gardening. www.rhs.org.uk. Published 2025. Accessed May 6, 2022. https://www.rhs.org.uk/plants/17359/silybum-marianum/details