-

How does it feel?

Anyone who likes sweet, aniseed, licoricey flavours, will find anise hyssop delicious. The aroma of sweetness and aniseed hits as soon as the infusion is brewed, with an edge of sourness in the scent. The strong fragrance informs of the high volatile oils content, which are easily evaporated in the steam, so cover the infusion as it is steeping. The taste is comparable to the aroma: sweet, aniseed, liquorice, slight sourness, and very delicately bitter. It leaves a watery feeling in the mouth as the salivary glands are stimulated by the sweetness, and the taste lingers in the mouth and throat from the volatile oils coating the surfaces.

There is a slight cooling sensation on the tongue, a characteristic common to mint-family herbs, owing to the high concentration of volatile oils. The hint of sourness indicates the presence of flavonoids, and highlights the antioxidant action which is dominant in this herb. Sour antioxidants (flavonoids) tend to cool the tissues and are protective against oxidative stress, which can lead to inflammation and heat (1). The sweet taste tends to indicate a nourishing and strengthening action, however this is when the sweetness comes from sugars and polysaccharides (1). In the case of anise hyssop, the sweetness is coming from the volatile oils, with actions on the digestive and respiratory systems.

The expectorant action can be felt quickly, with a loosening of mucus, a running nose, and the desire to clear the chest and throat. The carminative active sweeps through the intestines, easing tension and bringing a sense of movement. The energetics are calming, grounding, and relaxing, with a downward movement through the body. This is balanced with the uplifting charm of the scent and taste sensation, that brings a comforting smile to the face. Aromatic oils are often lifting and awakening to the olfactory (smelling) sense (1). This delightful infusion encourages you to sit and enjoy a moment of calm, quiet, joy, ease and pleasure, which really lifts the spirits.

-

What can I use it for?

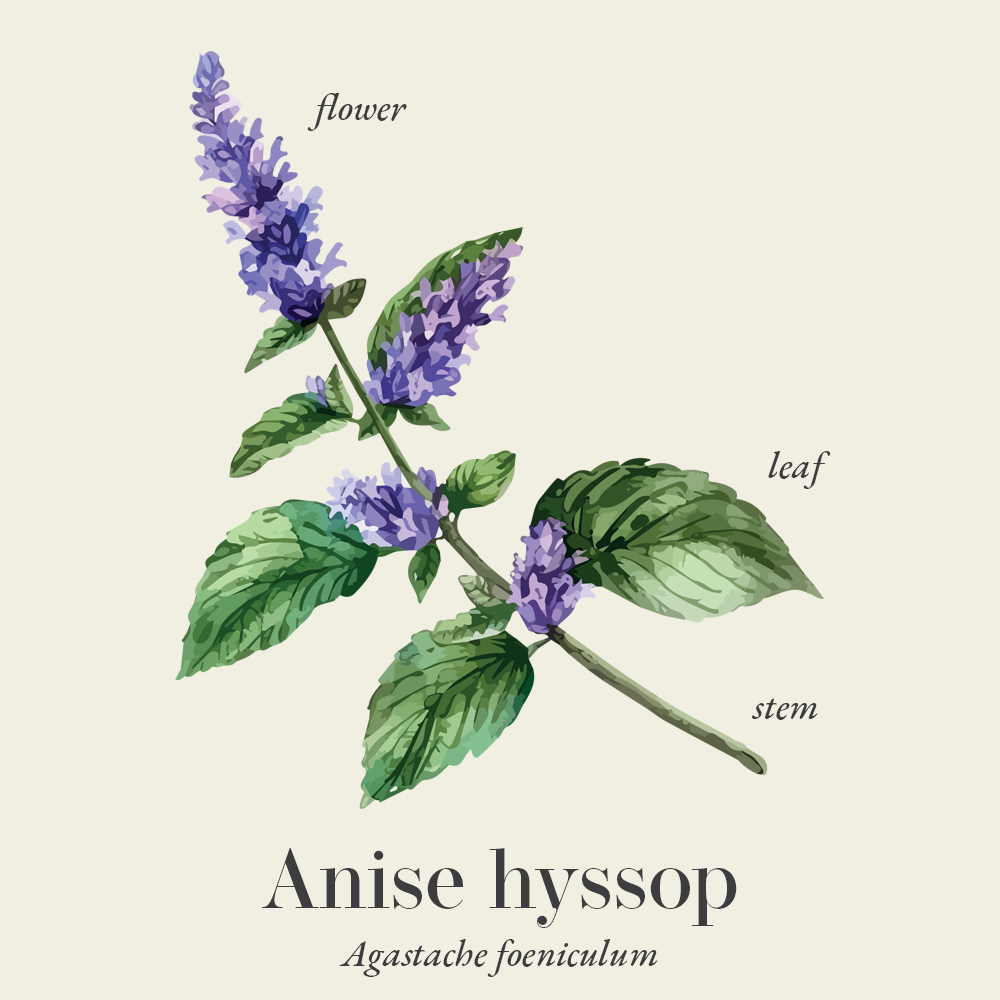

Anise hyssop (Agastache foeniculum) Despite the similarity in the names, anise hyssop (Agastache foeniculum) is not the same plant as hyssop (Hyssopus officinalis), or aniseed (Pimpinella anisum). Although, anise hyssop and hyssop are both in the mint (Lamiaceae) family, and they have similar actions. For such a pleasant tasting herb, with a long history of use, anise hyssop is sadly missing from many modern dispensaries. The most common modern use of anise hyssop seems to be as an ornamental garden plant, due to its attractive flowers, scented foliage and ecological role in attracting pollinators (2,3).

Anise hyssop was traditionally applied as a medicine for acute respiratory illness, functional disorders of the gastrointestinal tract, inflammatory diseases of the urinary system, as well as topical applications (4). It is expectorant, soothing, anti-inflammatory, and diaphoretic, making it useful for relieving congestion, coughs, colds and fever (4). The antimicrobial qualities, particularly antibacterial actions, make it effective for treating infected lung conditions such as bronchitis and other respiratory tract infections.

Anise hyssop is also a digestive stimulant, and either an infusion as a tea, or the tincture, are warming digestive aids. As a carminative it will help to relieve flatulence and colicky pains, and can be taken to ease nausea and diarrhoea (4).Externally, anise hyssop can be used as a poultice, compress or wash, to help heal burns and mild wounds, or reduce itching from stings and rashes. It can be made into an effective bath or foot bath to cool the skin, soothe sunburn, or treat fungal infections such as athletes foot or yeast overgrowth (2,5,6).

Anise hyssop leaves and flowers can be used as a culinary herb by adding to food (2). It can be chopped into salads or fruit, used in cakes and desserts, and added as an attractive and aromatic garnish to any meal (2,7). Simply chewing on the leaf or flower can be used as an effective breath freshener (5).

-

Into the heart of anise hyssop

Anise hyssop (Agastache foeniculum) Anise hyssop is characterised by the dominance of flavonoids and phenolic acids, as well as volatile compounds, particularly monoterpenes (6). Estragole appears to be the volatile compound found in the highest concentration in anise hyssop (6,8). Estragole is highly aromatic, contributing to the sweet, anise-like scent and flavour, and the antimicrobial and antioxidant actions (8).

The volatile oils are reputed to be useful for their varying antimicrobial action, a quality of anise hyssop which has research evidence to support (9). Whole extract of anise hyssop has antibacterial activity against several bacterial strains including Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus haemolyticus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Streptococcus pneumoniae (6). The essential oil extracted from anise hyssop has antimicrobial activity effects on some gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens, Listeria monocytogenes, Bacillus subtilis) and gram-negative bacteria (Salmonella sp., Proteus vulgaris, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginos, Pneumonia vulicans (6,10,11,12).

There are a range of phenolic constituents in anise hyssop, such as quercetin and genistein in the highest quantities (8). Phenolic compounds tend to be potent antioxidants, with a protective action on many structures of the body (13). Anise hyssop has high antioxidant activity against a range of free radicals, thereby reducing oxidative stress (6,8,14). Oxidative stress is known to influence various chronic degenerative diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, inflammatory diseases, ageing, carcinogenesis, or arthritis, and the balance between oxidants and antioxidants in the body can have a significant effect on human health (8).

The phenolic compounds in anise hyssop, specifically acacetin and ursolic acid, also have antispasmodic action (6). This spasmolytic action of ursolic acid and acacetin has been demonstrated in animal studies, showing a blockage of receptors on the intestinal wall and reduced intestinal spasms (15). Ursolic acid and acacetin also have an antinociceptive action, creating an analgesic effect comparable to the medication diclofenac, in mice (15). Estragole, the main component of the volatile oils, has muscle relaxant, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial properties, further contributing to the therapeutic action on the intestines (8).The gastroprotective effect can also be explained by anise hyssop causing an increased secretion of gastric mucus and the inhibition of inflammatory cells (6). The tannins found in anise hyssop have astringent and antimicrobial properties, supporting the gut lining and mediating diarrhoea (9).

Energetically, anise hyssop is warm and dry, used to clear excessive dampness from the stomach and spleen, and heaviness from the chest (5). Plants which are high in volatile oils tend to be warming, drying, and moving as they stimulate the senses and promote digestion (1). These energetic actions are directed at the lungs, dispersing energy and shifting stagnation in this organ (1).

As a flower essence is said to bring sweetness after the weight of guilt and shame, lightening the heart. It is useful as a post-trauma stabiliser, supporting body and soul integration and aiding the ability to forgive, and accept forgiveness.

-

Traditional uses

Anise hyssop (Agastache foeniculum) Anise hyssop is native to North America and is not mentioned in old European herbal texts, but it featured prominently in Native American ethnobotanical traditions. It was not known in European countries until recently, and only appears in a modest number of modern herbal resources. The earliest recorded uses come from Indigenous communities rather than European herbalists and pharmacopoeia’s. Many Indigenous tribes in America refer to the species as bear mint, horse mint, and elk mint, and used it as a tea for colds, coughs, and a weak heart (9).

Tribes such as the Cree, Cheyenne and Ojibwe used it for respiratory ailments, fevers, digestive support and as an external application on burns (7). An infusion of the leaves was specifically used to treat heart conditions and chest pain from coughing (7). It was also brewed as a calming tea, and used to sweeten foods (7). It was used in sweat lodge ceremonies, and in baths to reduce a fever by inducing sweating (7). Native Americans also included it in their medicine bundles, burning it as incense for protection (4).

In Western herbal practice the leaves have traditionally been used as a poultice for burns, fever, headaches, heatstroke and herpes (5). In traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) anise hyssop is used to treat nausea, vomiting, fever, headaches, colds, indigestion, poor appetite, diarrhoea, and externally for tinea (ringworm) on the hands and feet (7).

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

-

What practitioners say

Anise hyssop is largely missed from the authoritative herbal texts and modern pharmacopeia’s, and absent from many herbal dispensaries. It is a very pleasant tasting herb with a history of traditional use as an antibacterial, anti-emetic, antifungal, diaphoretic, expectorant and digestive stimulant (2,5).

Respiratory system

As with many of the mint-family herbs, anise hyssop is an effective herb for supporting the respiratory system. The aromatic oils give it the delightful aroma, and are antimicrobial and expectorant. This helps to clear catarrh and supports the mucus membranes in the upper respiratory tracts (5,16). In order to clear the sinuses and restore function to the delicate mucus membranes in the respiratory tracts, combine anise hyssop with ground ivy (Glechoma hederacea), plantain (Plantago lanceolata), and eucalyptus (Eucalyptus spp).

Anise hyssop is a useful herb to add to remedies for the common cold, congestion, flu, or a fever. It combines well with elderflower (Sambucus nigra), elderberry, peppermint (Mentha piperita), and yarrow (Achillea millefolium). It also works well for persistent coughs, combining well with hyssop and mullein (Verbascum thapsus) and liquorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra). Where there are any signs of infection in the chest or in cases of bronchitis, the antimicrobial action can be enhanced by combining with thyme (Thymus vulgaris), elecampane (Inula helenium), and ginger (Zingiber officinale).

Anise hyssop is a welcome addition to any remedy, particularly when feeling unwell with an acute illness, to bring sweetness along with the expectorant, antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory actions.

Digestive system

Anise hyssop is a wonderful herb to include in remedies for bloating, colic, diarrhoea, morning sickness, nausea, and poor appetite (5). Anise hyssop is an aromatic carminative due to the constituents within the aromatic oils, which have an antispasmodic and anti-inflammatory effect on walls of the alimentary canal (16). The antispasmodic effect on the intestinal tissues explaining its use in folk medicine for abdominal pain and other gastrointestinal diseases (6).

The gastroprotective effects are also linked to the increased secretion of gastric mucus and the inhibition of inflammatory cells (6). Together, the antispasmodic, anti-inflammatory and analgesic actions of the constituents in anise hyssop reinforce its use as a therapy for visceral pain in the digestive tract, as applied in traditional medicine (6,8,15). These gastroprotective effects support its use as a medicinal plant in the treatment of digestive disorders such as in acute gastritis, dyspepsia, nausea, and vomiting (6).

Anise hyssop makes a delicious tea to drink after meals, to aid digestion. It combines well with hyssop, fennel (Foeniculum vulgare), aniseed, and helps to take the edge off digestive bitter herbs like angelica (Angelica archangelica) or chicory root (Cichorium intybus). You can read more about digestive health here.

Skin health

The leaves of anise hyssop were traditionally used as a poultice for burns and herpes, and this is supported by modern research showing improved wound healing and reduced skin inflammation (17). Anise hyssop has high antioxidant activity against a range of free radicals, reducing oxidative stress (6,14). Chronic wounds are frequently hindered by high levels of reactive oxygen species, which perpetuate inflammation and delay healing (17). Antioxidants could mitigate oxidative stress, reduce inflammation and promote wound repair (17). Anise hyssop can be used as a wash from a strong infusion, or incorporated into creams and balms for wound healing. Explore our article on how to make herbal creams.

-

Research

Anise hyssop (Agastache foeniculum) There is a lack of clinical evidence from human trials to support the use of anise hyssop, and the indications for use are largely based on traditional use. There is some in vitro research to determine the plant constituents, and some in vivo animal studies of whole extracts and isolated constituents.

Changes in major bioactive compounds with antioxidant activity of Agastache foeniculum, Lavandula angustifolia, Melissa officinalis and Nepeta cataria: Effect of harvest time and plant species

This study identified the bioactive compounds in anise hyssop, as well as the developmental stage when these constituents are highest, and the optimum time of day to harvest. The study investigated the antioxidant activity and polyphenolic content of the anise hyssop extracts, prepared from plants harvested at two phenological phases of development (beginning of blooming and full bloom), and at two time points (11 am and 4 pm). There was a high phenolic acid and flavonoid content across the samples, and high antioxidant activity. The best stage for harvesting the plants to have maximum amount of bioactive compounds was at the beginning of blooming (the first period of June) and in the afternoon (14).

Comparative study of useful compounds extracted from Lophanthus anisatus by green extraction

This study determined the essential oil (EO) components in Agastache foeniculum (Lophanthus anisatus) extracted from different parts of the plant. The study compared different extraction processes: hydro-distillation (HD); bio-solvent assisted distillation (BiAD); and, supercritical fluid extraction with CO2 and ethanol co-solvent (SCFE). The EO yield values varied for the method of extraction, increasing for each method, respectively.

The different parts of the plant provided different amounts of EO, with the flowers giving the highest, followed by the leaves, then the whole aerial parts. The values were 0.62, 0.92, 1.26 g/100 g for the whole aerial plant, 0.75, 1.06, 2.04 g/100 g for the leaves, and 1.22, 1.60 and 2.51 g/100 g for the flowers, for HD, BiAD, and SCFE, respectively. The main EO constituents in anise hyssop were: Estragon (30–93%), limonene (8%), eugenol (30%), chavicol (14%), benzaldehyde, and pentanol. Antimicrobial effects were demonstrated against Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (11).

Effects of Agastache foeniculum essential oil on skin wound healing in mice

This study examined the effect of a topical application of anise hyssop (Agastache foeniculum) essential oil to wound healing, in mice. Over nine days, either Agastache foeniculum (AGS), sham (SH), or, soybean oil (SB) were applied to wounds, and the healing response measured until day 14. Compared to the control groups, the AGS group demonstrated significantly: Accelerated wound healing; higher total antioxidant capacity; lower markers of oxidative stress; elevated collagen deposition; reduced inflammation; and enhanced tissue remodelling. These findings indicate that anise hyssop essential oil supports wound healing through antioxidant and anti-inflammatory mechanisms, highlighting its therapeutic potential in wound management (17).

-

Did you know?

The genus name “Agastache” comes from the Greek word meaning “many spiked”, referring to the many-spiked storks and flower heads on the plant (5). The species name “foeniculum” derives from the Greek foenum, meaning “fragrant hay”, on account of the delightful aroma of the plant (5).

Additional information

-

Botanical description

Anise hyssop is a deciduous, herbaceous perennial in the mint family, with aromatic green, leafy upright stems, growing to 0.5–1 m tall (3). The dark green leaves are roughly textured and have soft, grey hairs on the underside (5).

The leaves are opposite along the stem, oval at the base, and pointed at the tip (5). It has slim, bottlebrush-like spikes of aromatic white, two-lipped tubular flowers, which appear from summer to autumn (3).

If the seedheads are left during the winter they provide architectural interest in flower borders, and a food source for birds and wildlife (3).

-

Common names

- Alabaster

- Blue giant hyssop

- Fragrant giant hyssop

- Lavender hyssop

- Liquorice mint

- Wonder honey plant

- Anise mint

- Bear mint

- Horse mint

- Elk mint

-

Safety

Anise hyssop is considered safe to consume.

When using the essential oil of anise hyssop it should not be taken internally or applied directly to the skin without being diluted in a carrier oil, cream, balm or wash (18).

-

Interactions

None known (5)

-

Contraindications

None known (5)

Herbs containing concentrations of essential oils should be avoided in pregnancy, and only consumed when breast-feeding under the guidance of a medical practitioner (19).

For further guidance, find a qualified medical herbal professional.

-

Preparations

- Infusion

- Tincture

- Essential oil*

* The essential oil should never be taken internally, and only applied to the skin when diluted in a carrier oil, cream, balm or wash (18).

-

Dosage

No formal pharmacopoeia dosing standards exist for anise hyssop. Recommendations are based on the traditional use and standard dosing for similar herbs.

- Tincture (1:3| 45%): 2–4 ml, three times per day

- Fluid extract (1:1 | 45%): 1–3 ml per day

- Infusion/decoction: 1–2 teaspoons (3–5 g) dried herb per cup, three times per day

The essential oil of anise hyssop should never be taken internally, and only applied to the skin when diluted in a carrier oil, cream, balm or wash (18).

-

Plant parts used

- Herba (above ground parts)

- Leaves and flowering tops

-

Constituents

- Polyphenols

- Flavonoids: Isoquercitrin, quercetin, acacetin, vanilin, genistein, hyperoside, rutin, rutoside, apigenin (6)

- Phenolic acids: Chlorogenic acid, rosmarinic acid, caffeic acid, p-coumaric acid, ursolic acid (6)

- Lignans: Agastinol, agastenol (8)

- Other polyphenols: Resveratrol, estragole, chavicol, eugenol, pentanol (6)

- Terpenes

- Monoterpenes: Limonene, menthone, 1,8-cineole, geraniol, and pulegone (6,11)

- Sesquiterpenes: β-caryophyllene, spathulenol, caryophyllene oxide (6)

- Other terpenes: Diterpenes (agastaquinone, agastol), triterpenes (betulin, betulinic acid, oleanolic acid), plant sterols including β-sitosterol and stigmasterol; carotenoids (8,10)

- Essential oil (0.9–1.8%)*: mostly monoterpenes and estragole (30–93%*) – limonene (8%), eugenol (30%), chavicol (14%), benzaldehyde, and pentanol (6,11,14)

* The different parts of the plant provide different amounts of EO, with the flowers giving the highest, followed by the leaves, then the whole aerial parts (11).

- Polyphenols

-

Habitat

Anise hyssop is native to North and Central America and Canada, growing primarily in the temperate biome (20,21). The Agastache genus includes 22 species which are almost exclusively native to North America (7). Anise hyssop has been introduced in Europe, growing in the wild in Austria and Germany, and widely cultivated in gardens across Europe (3,20).

It is widely cultivated and has naturalised in some areas outside its native range, but it is not considered invasive or ecologically disruptive (21). Anise hyssop naturally grows in prairies, dry upland forested areas, plains, and open fields, preferring well-drained soils and full sun to partial shade (21,22).

-

Sustainability

Anise hyssop does not have a globally recognised conservation status ranking by the International Union of Conservation of Nature, and does not appear on any National red lists (9,23,24). It is reported as “secure” by NatureServe since it is widespread, abundant, and not currently facing any significant threats across its native range of central and North America and parts of Canada (9,21). A

nise hyssop is not listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act or by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), and does not appear on the United Plant Savers list of threatened species (9,26). It is not listed by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), with no legislation regarding trade of the species (25).

Trade in the plant is considered to be minor, and because it grows readily and quickly from seed, it is presumed that if wild collection of this species increases in the future, the impact on wild populations could be offset rather easily by cultivation (9).

Read our articles on How to substitute endangered herbs, Herbal quality & safety: What to know before you buy and Sustainable sourcing of herbs to learn more about what to look for and questions to ask suppliers about sustainability.

-

Quality control

Herbal medicines are often very safe to take; however, their safety and efficacy can be jeopardised by quality issues. So, it is important to buy herbal medicines from a reputable supplier, from sources known to test their herbs to ensure there is no contamination, adulteration or substitution with incorrect plant matter, as well as ensuring that recognised marker compounds are at appropriate levels in the herbs.

Some important quality assurances to look for are certified organic labelling, the correct scientific/botanical name, and the availability of information from the supplier about ingredient origins. A supplier should be able to tell you where the herbs have come from, what contaminants are not in the herb, and what the primary compounds are.

-

How to grow

Propagation is by seed, cutting or division, in spring (3,22). The seeds require warmth and light to germinate (2). Sow in a greenhouse and lightly cover with perlite, and allow 1–3 months for germination (22). Prick out the seedlings into individual pots when they are large enough to handle, and grow them in the greenhouse for their first year before planting out in late spring or early summer (22). Division in spring is simple, as soon as the foliage starts to appear, and it is possible to plant straight out into their permanent position (22).

Basal cuttings can be taken from the young shoots in spring when they are about 10–15 cm tall, and potted in a greenhouse they should root within three weeks, and can be planted out in the summer or following spring (22).

Anise hyssop prefers well drained, fertile soil in full sun (3). It is not fully drought resistant but is considered low maintenance (3). The flower spikes can be removed through the summer to encourage more growth, but left in autumn provides seed heads for insects and wildlife (3). The best time to harvest for the optimal medicinal value is as the flowers begin to bloom, collecting them in the afternoon sun (3).

-

Recipe

Anise hyssop infused honey

This simple herbal infusion captures the aromatic, slightly sweet, floral, minty-anise, and liquorice-like flavour of anise hyssop. It is perfect to add to teas to add flavour or soothe sore throats and coughs. Or, it can be used as a culinary medicinal by adding to desserts, fruit, yogurt, pancakes or spreading on toast.

Ingredients

- Anise hyssop leaves and flowers. Fresh is ideal, but can be made with dried herb if necessary.

- Raw, local honey

How to make anise hyssop honey

- Take a clean, sterile jar and fill with fresh anise hyssop leaves and flowers, or fill halfway with dried herb. Lightly bruise the fresh herb to release the oils.

- Pour honey over the herbs until fully submerged. Use a spoon or knife to remove any air bubbles. This may need to be repeated over the next few days to ensure the herb remains covered and any air bubbles are released.

- Seal the jar and leave to infuse for 1–2 weeks in a warm, dark place. Turn or shake gently every few days.

- Strain through a fine sieve or cheesecloth into a clean jar. Label with date and ingredients.

- Store in the fridge and use within six months.

- Add to herbal teas or drizzle over food.

-

References

- Maier K. Energetic Herbalism: A Guide to Sacred Plant Traditions Integrating Elements of Vitalism, Ayurveda, and Chinese Medicine. Chelsea Green Publishing; 2021.

- McVicar, J. Jekka’s Complete Herb Book. Kyle Cathie Limited; 2009.

- Royal Horticultural Society. Agastache foeniculum: anise hyssop ‘Alabaster’. Accessed November 16, 2025. https://www.rhs.org.uk/plants/47316/agastache-foeniculum-alabaster/details

- Duda MM, Vârban DI, Muntean S, Moldovan C, Olar M. Use of species Agastache foeniculum (Pursh) Kuntze. Hop and Medicinal Plants. 2013; 21(1-2), 52–54. https://doi.org/10.15835/hpm.v21i1-2.10071

- Mars, B. The Desktop Guide to Herbal Medicine. Basic Health Publications Inc; 2007.

- Nechita MA, Toiu A, Benedec D, et al. Agastache Species: A Comprehensive Review on Phytochemical Composition and Therapeutic Properties. Plants (Basel). 2023;12(16):2937. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12162937

- Fuentes-Granados RG, Widrlechner MP, Wilson LA. An overview of Agastache research. Journal of Herbs, Spices & Medicinal Plants. 1998 Jan 1;6(1):69-97. https://doi.org/10.1300/J044v06n01_09

- Bălănescu F, Botezatu AV, Marques F, Busuioc A, Marincaş O, Vînătoru C, Cârâc G, Furdui B, Dinica RM. Bridging the Chemical Profile and Biological Activities of a New Variety of Agastache foeniculum (Pursh) Kuntze Extracts and Essential Oil. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023; 24(1):828. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24010828

- NatureServe explorer 2.0. Natureserve.org. Accessed November 16, 2025. https://explorer.natureserve.org/Taxon/ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.137289/Agastache_foeniculum

- Ivanov IG, Vrancheva RZ, Petkova NT, Tumbarski Y, Dincheva IN, Badjakov IK. Phytochemical compounds of anise hyssop (Agastache foeniculum) and antibacterial, antioxidant, and acetylcholinesterase inhibitory properties of its essential oil. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science. 2019;9(2):072-8. DOI: 10.7324/JAPS.2019.90210

- Stefan DS, Popescu M, Luntraru CM, et al. Comparative Study of Useful Compounds Extracted from Lophanthus anisatus by Green Extraction. Molecules. 2022;27(22):7737. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27227737

- Hashemi M, Ehsani A, Hassani A, Afshari A, Aminzare M, Sahranavard T, Azimzadeh Z. Phytochemical, antibacterial, antifungal and antioxidant properties of Agastache foeniculum essential oil.

- Pengelly A. The constituents of medicinal plants: an introduction to the chemistry and therapeutics of herbal medicine. CABI Publishing; 2004.

- Duda SC, Mărghitaş LA, Dezmirean D, Duda M, Mărgăoan R & Bobiş O. Changes in major bioactive compounds with antioxidant activity of Agastache foeniculum, Lavandula angustifolia, Melissa officinalis and Nepeta cataria: Effect of harvest time and plant species. Industrial Crops and Products, 2015; 77, 499-507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.09.045

- González-Trujano, M.E.; Ventura-Martínez, R.; Chávez, M.; Díaz-Reval, I.; Pellicer, F. Spasmolytic and Antinociceptive Activities of Ursolic Acid and Acacetin Identified in Agastache mexicana. Planta Medica. 2012, 78, 793–796. https://dio.org/10.1055/s-0031-1298416

- Hoffmann D. Medicinal Herbalism, The Science and Practice of Herbal Medicine. Healing Arts Press; 2003.

- Abbasi F, Jafarbeglou A, Davoodi F, et al. Effects of Agastache foeniculum essential oil on skin wound healing in mice. Tissue Cell. 2025;96:102995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tice.2025.102995

- Curtis S, Thomas P, Johnson F. Neal’s Yard Remedies Essential Oils: Restore, Rebalance, Revitalize, Feel the Benefits, Enhance Natural Beauty, Create Blends. Dorling Kindersley Ltd; 2016.

- Brinker, FJ. Herbal Contraindications & Drug Interactions: Plus Herbal Adjuncts with Medicines. Eclectic Medical Publications, 2010.

- Royal Botanical Gardens Kew (RBGK). Agastache foeniculum. Pursh. Plants of the Word Online (POWO). Accessed November 16, 2025. https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:6304-2

- USDA. United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. Agastache foeniculum (Pursh) Kuntze blue giant hyssop. PLANTS Database. Accessed November 16, 2025. https://plants.usda.gov/plant-profile/AGFO

- PFAF. Agastache foeniculum – (Pursh.)Kuntze. PFAF Plant Database. Accessed November 16, 2025. https://pfaf.org/user/plant.aspx?LatinName=Agastache+foeniculum

- IUCN red list of threatened species. Accessed November 16, 2025. https://www.iucnredlist.org/

- Cheffings C, Farrell L, (eds), Dines, T.D., Jones, R.A., Leach, S.J., McKean, D.R., Pearman, D.A., Preston, C.D., Rumsey, F.J., Taylor, I. The Vascular Plant Red Data List for Great Britain. Species Status No. 7. Joint National Conservation Committee. 2005. Accessed November 16, 2025. https://hub.jncc.gov.uk/assets/cc1e96f8-b105-4dd0-bd87-4a4f60449907

- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Accessed November 16, 2025. https://checklist.cites.org/#/en

- UpS list of herbs & analogs. United Plant Savers. Published May 14, 2021. Accessed November 16, 2025. https://unitedplantsavers.org/ups-list-of-herbs-analogs/