-

Herb overview

Safety

Can cause gastric irritation if not adequately processed

Sustainability

Low risk/Green

FairWild certified rosehips availableKey constituents

Vitamins

Flavonoids

PolyphenolsQuality

Native to Europe, Western Asia, and North Africa

Mostly wild-harvested

Risk of botanical substitution with other Rosa speciesKey actions

Immunomodulant

Anti-inflammatory

Astringent

AntioxidantKey indications

Cold and flu

Infection

Skin healthKey energetics

Cooling

AstringentPreperation and dosage

Fruit

10 g/per day

6–12 ml daily

-

How does it feel?

Rosehips have a dynamic taste profile with an initial sweet zing followed by a sour or sharp taste sensation. From a flavour perspective, they could be seen as a native schisandra (Schidandra chinensis) — a popular Chinese medicine also known as five flavour berry due to its dynamic taste profile. Rosehip is sweet, sour, salty, aromatic and astringent. As a tea, syrup or tincture — its taste is enjoyed by most, making it a fantastic remedy for all the family.

-

Into the heart of rosehip

Rosehip (Rosa canina) Energetically, rosehips are sweet and cooling. They also have an interestingly contrasting action upon the tissues. They have both toning, astringent qualities but are also soothing and demulcent.

The actions of astringent plants such as those found in the rose family (i.e. lady’s mantle (Alchemilla vulgaris), hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna) and rose flower (Rosa damascena) are all valuable for this strengthening effect on the mucous membranes. They have the ability to tone and moderate tension, improving the boundaries between the inner and outer regions. It is the additional mucilaginous quality of rosehips that also soothes, coats and protects the tissues (6).

Rosehips’ effects on the tissues are fairly neutral due to these contrasting actions. This means that it works as an amphoteric to bring balance. This may be applied where there is a loss of tone. Contrastingly, it may also be applied where there is an excess in tension, which is sometimes indicated by a spasmodic or excited tissue state or by a dry, irritated and inflamed state in the mucous membranes. A herbalist will use rosehip to balance and restore integrity in the tissues (6).

These actions are also understood to work on emotional boundaries. Rose has long been associated with the emotional heart and feelings of love. As a herb that works on the emotional heart, rosehip is also understood to bring healing in grief, loss and depressive states. Much like the flowering parts of rose, which are also used in herbal medicine.

The holistic understanding of the interconnectedness between the physical and emotional systems indicates that often where there is emotional tension, there is also physical tension. Rosehip (and rose alike) would, therefore, be a supportive choice to alleviate both.

In Ayurvedic medicine, there is a different model and understanding of what each organ does and how they connect. Ayurveda has its own unique philosophy and understanding of bodily systems and herbal qualities that have been built up over thousands of years of observation.

According to the Ayurvedic understanding of herbal energetics, rosehip is sour and astringent. The ayurvedic tradition describes rosehip as warming. . In terms of the doshas, rosehip is used to reduce excess vata and raise the qualities of kapha and pitta (7).

-

What practitioners say

Cardiovascular system

Cardiovascular systemRosehips’ antioxidant properties support and protect the heart and cardiovascular system. They enhance the integrity of the entire vascular system reducing capillary fragility and permeability. Rosehips are used for the long-term treatment of varicose veins and degenerative vascular diseases, such as atherosclerosis and hypertension (11. Rosehips have been shown to reduce LDL cholesterol, lower blood pressure and reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease (11).

Immune system

Due to the high levels of antioxidants, vitamin C and nutritive compounds in rosehip, it is used by herbalists to support and strengthen the immune system. It is also an immunomodulator, which is one of the ways by which it helps to lower the inflammatory effects of autoimmune conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis. Rosehips have also been shown to stimulate the production of white blood cells, help to improve immune resistance and protect against infections (12).

Musculoskeletal system

Rosehip has a number of indications for inflammatory conditions in the musculoskeletal system, such as rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Herbalists use rosehip to reduce inflammation and pain via a modulating effect on the immune system. Rosehip inhibits proinflammatory cytokines and NF-κB signaling and reduces C-reactive protein (13). Rosehip powder has also been effective in reducing pain and inflammation amongst patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis (13,14).

Urinary system

Rosehip has a diuretic action, which means that it can be used for conditions of the kidneys and lower urinary tract. It is highly antioxidant and also supports blood purification through the kidneys. Rosehip is an excellent medicine to support healing in the urinary tract during and after an acute urinary tract infection, providing the infection has been appropriately managed (3).

Digestive system

Rosehip infusion coats and soothes the mucous membranes, due to its mucilaginous properties. The mucilage coats the digestive tract, calming and protecting the digestive tissues after acute stomach illness, antibiotic use, dysentery, or giardia. The mucilaginous quality soothes the digestive tract and helps to alleviate constipation (15).

Skin health

A topical preparation of rosehip is used for a variety of skin complaints. Research suggests that it can aid in the healing of surgical wounds and ulcers. Rosehips have been shown to promote collagen synthesis and support skin repair and regeneration. The retinoids also facilitate skin cell turnover and reduce inflammation. This contributes to its use in skin care products to support ageing skin (5).

-

Rosehip research

Rosehip (Rosa canina) The effects of a standardised herbal remedy made from a subtype of Rosa canina in patients with osteoarthritis: A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial

This trial explored the effect an extract made from rosehip powder had on joint mobility, daily life, quality of life and pain in osteoarthritis patients. One hundred participants were included, with half receiving five doses of 0.5 g of rosehip powder extract twice daily for four months and the other half receiving placebo. The results showed significant improvement in joint mobility and a reduction in pain in the rosehip group compared to placebo (16).

Effects of daily Intake of rosehip extract on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and blood glucose levels: A systematic review

This systematic review analysed four randomised clinical trials that studied the impact of rosehips on lipid profiles and blood glucose levels. The dosages varied between 40 g powder to 100 mg to 750 mg in tablets taken once or twice daily for between 6–12 weeks. Results showed significant reductions in LDL cholesterol, fasting blood glucose and HbA1c. Secondary measures included reductions in body weight, systolic blood pressure, abdominal fat and cardiovascular risk scores. Rosehip was well tolerated with limited adverse effects (11).

Bioactive ingredients of rose hips (Rosa canina L) with special reference to antioxidative and anti-inflammatory properties

A review was carried out on a number of in vitro studies that investigated the effects of different compounds extracted from rosehips. A promising body of evidence is compiled which shows the actions of many compounds found in rosehips such as flavonoids, carotenes, polyphenols and essential fatty acids shows a clear evidence base for being anti-inflammatory and exhibiting antioxidant mechanisms in vitro. As these in vitro studies focus on extractions presented to cells in a test tube they lack true insight into how biologically complex whole plant extracts work in the human body. It is clear that further clinical trials with larger sample sizes are needed (12).

Rose hip herbal remedy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis — a randomised controlled trial

A double-blind placebo-controlled trial was carried out to investigate the effectiveness of rosehip on 89 patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Subjects were randomised to receive treatment with capsulated rose-hip powder at 5 g daily or with a placebo over a period of six months. The results show that the rosehip group made significant improvements in various pain measurements, as well as parameters that indicate quality of life. The placebo group, however, worsened. This indicates that rosehip is effective in treating patients with rheumatoid arthritis (18).

Does the hip powder of Rosa canina (rosehip) reduce pain in osteoarthritis patients? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials was carried out on rosehip powder for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Overall, three studies were evaluated with a cumulative study group of 306 patients. The studies showed a reduction in pain scores in the rosehip powder group when compared with the placebo group (19).

The effectiveness of a standardised rose hip powder, containing seeds and shells of Rosa canina, on cell longevity, skin wrinkles, moisture, and elasticity

During an eight week double blind study the effects of rosehip powder on skin ageing were investigated. A total of 34 healthy subjects, aged 35–65 years who received the rosehip displayed significant improvements in crow’s feet, wrinkles, skin moisture, and elasticity. The study concludes that rosehip taken internally has several anti-ageing properties (14).

Rosehip oil promotes excisional wound healing by accelerating the phenotypic transition of macrophages

Results showed that rosehip oil significantly promoted wound healing and effectively improved scars. This efficacy might have happened because of accelerating macrophage phenotypes transition to the wound. Macrophages are types of white blood cells that facilitate wound healing, and there are different types that release different chemical signals that facilitate the healing process. Rosehip was shown to increase this mechanism of action. The oil also helped with improving scars as it inhibited the process of epithelial-mesenchymal transition which is a tissue forming process which causes scars (19).

Effects of rose hip intake on risk markers of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease: a randomised, double-blind, cross-over investigation in obese persons

A randomised, double-blind, cross-over investigation was carried out to evaluate the effects of rosehip powder drink (40 g powder) on risk markers of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease in obese subjects. A total of 31 obese individuals with normal or impaired glucose tolerance were enrolled. The study results showed that six weeks of daily consumption of the rosehip drink resulted in a significant reduction of systolic blood pressure, total plasma cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and LDL/HDL ratios. The study concludes that rosehip powder can significantly reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease in obese people through the lowering of systolic blood pressure and plasma cholesterol levels (20).

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

Western energetics

-

What can I use rosehip for?

Rosehip (Rosa canina) Rosehips are a wonderful and simple foraged food and medicine that can be harvested in autumn and made into a wide range of medicines. Although it is important to note that one must firstly remove the hairy seeds as they are an irritant to the digestive system. The flesh is high in antioxidant compounds, vitamins and minerals making it a truly valuable nutritive tonic. It is thought to be one of most potent sources of vitamin C found in any fruit or vegetable, hence rosehips are often used in vitamin C supplements (1).

Rosehips’ medicinal properties are much attributed to their astringent and antioxidant actions. The tea is also beneficial as a demulcent for treating a sore throat. Rosehip can be an excellent support to the immune system for colds and acute viral infections. They can be used as a preventative throughout the early stages of a virus and to treat the symptoms throughout. They have been shown to exhibit antiviral properties by inhibiting viral replication (2). Rosehips are also an excellent tonic to help in the convalescence stages of such illnesses.

Their anti-inflammatory effects are useful as part of a supportive approach for rheumatic conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis (3). However, when treating more chronic, life-limiting conditions it is recommended to consult with a professional herbalist. In traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), rosehips are used to promote the movement of qi and blood in the lower abdomen and, therefore, are often used to alleviate painful and heavy menstruation (4).

Rosehips are renowned not only for internal use, but also externally as a popular cosmetic to support healthy, glowing skin. Its rich vitamin C and antioxidant content prevent oxidative stress on the skin cells, reduce scarring and support skin elasticity (5). It is often referred to as an anti-ageing agent, due to the moisturising effects of the fatty acids and presence of retinoids which promote skin regeneration (5).

-

Did you know?

Rosehips are one of the highest sources of bioavailable vitamin C in fruits and vegetables, with 426 mg per 100 g (21).

-

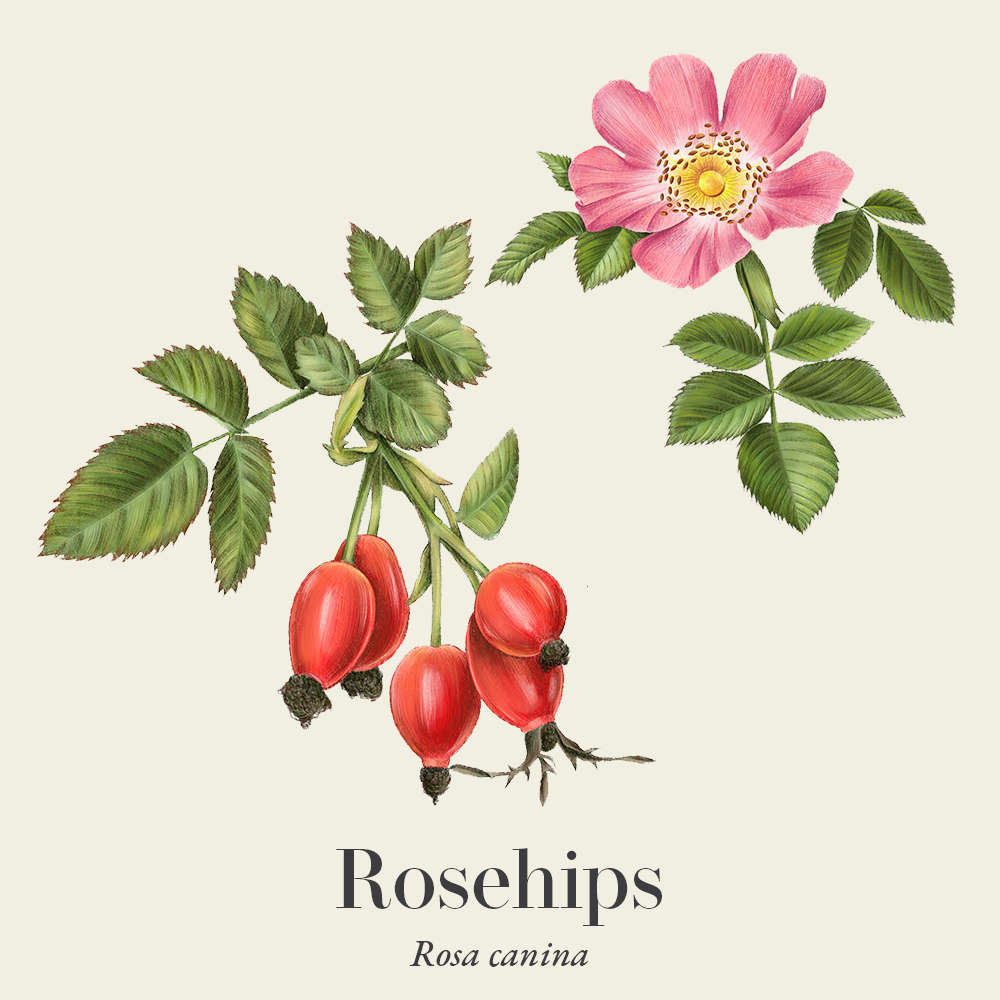

Botanical description

Rosa canina is a deciduous or semi-evergreen shrub or scrambling climber, usually with thorny arching stems bearing compound pinnate leaves and solitary or clustered flowers. It grows rapidly up to nine feet in height.

Flowers are single or small clusters with five-petals ranging in colour from white to pink appear in June and July and are followed by bright red persistent fruit or pseudo-fruit (hips) in September and October. The actual fruit is the small hairy structure within the hip that contains one seed (24).

-

Common names

- Hips

- Dog rose

- Dog brier

- Brier rose

- Apothecary rose

-

Habitat

Rosehips are native to Europe and are the most common Rosa species with the widest distribution in central Europe. The shrub is most often found in hedgerows, woodland edges and scrubland (25).

-

How to grow rosehip

Dog rose is a hardy shrub which is easy to grow. It will thrive in full to partial sun placed usually in the middle or back of a garden border or edge.It is advised to source a small bare-root plant through a local garden centre, although a more advanced gardener may grow a rose from seed or more commonly from hardwood cuttings.

Dog rose is best planted out in autumn but failing that, it can be planted in early spring.

Place your bare rooted rose directly into a moist but well-drained soil either straight in situ or in a large ceramic pot.

This species requires little feeding but will benefit from a feed in spring using an organic fertiliser. This will encourage good growth. Choose a fertiliser which is high in potash, such as tomato fertiliser.

Roses need watering occasionally during the warmer months, particularly in hotter climes.

To maintain its shape, prune back older stems to around 30 cm above ground level, from late autumn to early spring (29).

-

Herbal preparation of rosehip

- Fresh or dried

- Powder

- Decoction

- Infusion

- Syrup

- Tincture

- Topical: Cold pressed or infused oil

-

Plant parts used

- Flower

- Fruit

- Seed

- Root

See the rose monograph for detailed information on the use of the flower.

-

Dosage

- Tincture: Rosehip tincture can be made from fresh or dried material. Fresh (1:2 or 1:3, 70–95%) or dry (1:5, 50–60%); either can be taken between 2–4ml up to three times a day (22).

- Infusion/decoction: Add 2.5 teaspoons of cut rose hips (small hairs removed) into around one cup of water and simmer for 10 minutes. Strain off the rosehips through muslin and drink up to three times a day (22).

-

Constituents

- Flavonoids: Quercetin, rutin, hesperidin, kaempferol

- Essential fatty acids: Linoleic and α-linolenic acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids

- Polyphenols

- Vitamins: Rosehips are packed full of vitamin C, E and B vitamins (riboflavin, niacin)

- Carotenoids: Betacarotene, lutein

- Minerals: Phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, manganese, selenium and zinc

- Fibre

- Pectins

- Volatile oil: A complex mixture of alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, terpenoids, and esters (24)

-

Rosehip recipe

Rosehip syrup

Rosehip syrup is a popular recipe among herbalists and foragers. It is sweet, zingy, incredibly healthy and easy to make. This recipe uses honey instead of refined sugar. However, sugar can be used instead. To make a syrup using fruiting plant medicines, one must first make a decoction or infusion. Follow the steps below.

Ingredients

- Rosehips

- Honey or sugar

- Water

How to make rosehip syrup

- Gather the rosehips or source dried rosehips from a local health food shop or herbalist. Freshly gathered whole rosehips will need deseeding. This is easy enough to do by cutting rosehips in half and gently scooping out the hairy seeds with a spoon. Ensure to remove them all and the tiny hairs as they can be an irritant to the digestive tract.

- Place your processed rosehips in a sieve and give them a rinse after removing the seeds, this will help wash away any tiny hairs that are stuck to the fruit.

- Place rosehips into a pot adding water at a ratio of around one part rose hips to two parts water (1:2). Bring it to a boil, then reduce the heat and simmer for 15–20 minutes, or until the water has reduced by about half.

- Remove the decoction from the heat and leave to cool for 10 or so minutes allowing for that final extraction before straining out the plant material into a sterile bowl. This may be done using cheesecloth (a minimum of three layers — to remove any remaining hairs) on top of a fine mesh sieve.

- Take a good look, and if there are still tiny hairs floating around it’s a good idea to strain it once again, maybe with even more layers of cheesecloth.

- Measure the quantity of decoction and then return to a clean pan on very low heat.

- Measure out the honey, or sugar. Using no less than three parts honey to one part decoction (1:3) to effectively preserve your syrup. Stir through the honey until it has fully dissolved.

- If you have a large quantity of decoction, you may simmer it down for a further 20- 30 minutes before adding honey or choose to store some in the freezer.

- Bottle up the syrup into sterile glass bottles and store in the fridge. It should last for up to six months.

Adults can take 1–2 tablespoons of rosehip syrup 2–3 times a day as a daily nutritive tonic to support health, though if one is diabetic then high sugar levels should be avoided. It can also be taken at the onset of a cold or flu. Children aged over one year may take 1 tsp a day and those aged three and up, can take 2–3 tsp a day. Rosehip syrup can also be used in smoothies, as a drizzle over deserts or in cocktails and smoothies.

-

Safety

The tiny hairs in rosehips can be an irritant to the digestive tract so it is not advisable to eat them raw, and they must be cooked and processed effectively (22). Rosehip is a very safe medicine that may be used by all ages (over one). Rosehip may be taken during pregnancy and breastfeeding at the correct dose.

-

Interactions

None known (6,22,23)

-

Contraindications

None known (6,22,23)

-

Sustainability status of rosehip

The commercial supply of rosehips is obtained primarily from wild-harvested sources in Eastern Europe. According to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Plants Status wild populations of dog rose remain abundant and it is classified as ‘least concern’ (26).

Sustainable wild-collection of dog rose fruit requires harvesting in a way that does not destroy twigs and branches. Sustainable herbs program suggests that a minimum of 20% of any individual plant’s fruits should be left on the tree to facilitate regeneration (8). Controlled cultivation of rosehips along with improved organic agriculture rules in wild harvesting of this species means that for a large majority — the global demand for rosehips can still be met through sustainable production methods (27).

Habitat loss and over-harvesting from the wild are two of the biggest threats faced by medicinal plant species. There are an increasing number of well-known herbal medicines at risk of extinction. We must, therefore, ensure that we source our medicines with sustainability in mind.

The herb supplement industry is growing at a rapid rate and until recent years a vast majority of medicinal plant produce in global trade was of unknown origin. There are some very real and urgent issues surrounding sustainability in the herb industry. These include environmental factors that affect the medicinal viability of herbs, the safety of the habitats that they are taken from, as well as the welfare of workers in the trade.

The botanical supply chain efforts for improved visibility (transparency and traceability) into verifiably sustainable production sites around the world is now certificated through the emergence of credible international voluntary sustainability standards (VSS).

Read our article on Herbal quality & safety: What to know before you buy and Sustainable sourcing of herbs to learn more about what to look for and questions to ask suppliers about sustainability.

-

Quality control

Rose (Rosa centifolia) Older texts suggest that it is best to harvest rosehips after the first frost. The frost breaks down the cell walls of the fruit, thereby giving you more liquid once the fruit is cooked. However in many places where rosehip grows the first frost is long after the fruiting season. The fruits may well rot or be eaten by birds and insects before which time. As a solution, one can simply freeze rosehips for 24 hours to optimise the flavour before using (29).

Herbal medicines are often very safe to take; however, their safety and efficacy can be jeopardised by quality issues. So, it is important to buy herbal medicines from a reputable supplier, from sources known to test their herbs to ensure there is no contamination, adulteration or substitution with incorrect plant matter, as well as ensuring that recognised marker compounds are at appropriate levels in the herbs.

Some important quality assurances to look for are certified organic labelling, the correct scientific/botanical name, and the availability of information from the supplier about ingredient origins. A supplier should be able to tell you where the herbs have come from, what contaminants are not in the herb, and what the primary compounds are.

-

References

- Mármol I, Sánchez-de-Diego C, Jiménez-Moreno N, Ancín-Azpilicueta C, Rodríguez-Yoldi M. Therapeutic Applications of Rose Hips from Different Rosa Species. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017;18(6):1137. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18061137

- Negrean OR, Farcas AC, Nemes SA, Cic DE, Socaci SA. Recent advances and insights into the bioactive properties and applications of Rosa canina L. and its by-products. Heliyon. 2024;10(9):e30816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e30816

- Cohen M. Rosehip An evidence based herbal medicine for inflammation and arthritis. Australian Family Physician. 2012;41(7). Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.racgp.org.au/afp/2012/july/rosehip

- Chen JK, Chen TT, Crampton L. Chinese Medical Herbology and Pharmacology. Art Of Medicine Press, Inc; 2004.

- Patricia D, Mihaiela Cornea-Cipcigan, Mirela Irina Cordea. Unveiling the mechanisms for the development of rosehip-based dermatological products: an updated review. Frontiers in pharmacology. 2024;15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2024.1390419

- Mcintyre A. Complete Herbal Tutor : The Definitive Guide to the Principles and Practices of Herbal Medicine (Second Edition). Aeon Books Limited; 2019.

- Frawley D, Lad V. The Yoga of Herbs : An Ayurvedic Guide to Herbal Medicine. Lotus Press; 2008.

- Breverton T, Culpeper N. Breverton’s Complete Herbal : A Book of Remarkable Plants and Their Uses. Lyons Press; 2011.

- Grieve M. A Modern Herbal. www.botanical.com. Published 1931. https://www.botanical.com/botanical/mgmh/mgmh.html

- Popović‐Djordjević J, Špirović-Trifunović B, Pećinar I, et al. Fatty acids in seed oil of wild and cultivated rosehip (Rosa canina L.) from different locations in Serbia. Industrial Crops and Products. 2023;191:115797-115797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.115797

- Malachy Belkhelladi. Effects of Daily Intake of Rosehip Extract on Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Blood Glucose Levels: A Systematic Review. Cureus. Published online December 28, 2023. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.51225

- Winther K, Campbell-Tofte J, Vinther Hansen AS. Bioactive ingredients of rose hips (Rosa canina L) with special reference to antioxidative and anti-inflammatory properties: in vitro studies. Botanics: Targets and Therapy. Published online February 2016:11. https://doi.org/10.2147/btat.s91385

- Pekacar S, Bulut S, Özüpek B, Orhan DD. Anti-Inflammatory and Analgesic Effects of Rosehip in Inflammatory Musculoskeletal Disorders and Its Active Molecules. Current Molecular Pharmacology. 2021;14(5):731-745. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874467214666210804154604

- Christensen R, Bartels EM, Altman RD, Astrup A, Bliddal H. Does the hip powder of Rosa canina (rosehip) reduce pain in osteoarthritis patients? – a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 2008;16(9):965-972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2008.03.001

- Odriozola-Serrano I, Danielle Pires Nogueira, Esparza I, et al. Stability and Bioaccessibility of Phenolic Compounds in Rosehip Extracts during In Vitro Digestion. Antioxidants. 2023;12(5):1035-1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox12051035

- Warholm O, Skaar S, Hedman E, Mølmen HM, Eik L. The Effects of a Standardized Herbal Remedy Made from a Subtype of Rosa canina in Patients with Osteoarthritis: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Current Therapeutic Research. 2003;64(1):21-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0011-393x(03)00004-3

- Willich SN, Rossnagel K, Roll S, et al. Rose hip herbal remedy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis – a randomised controlled trial. Phytomedicine. 2010;17(2):87-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2009.09.003

- Phetcharat L, Wongsuphasawat K, Winther K. The effectiveness of a standardized rose hip powder, containing seeds and shells of Rosa canina, on cell longevity, skin wrinkles, moisture, and elasticity. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2015;10:1849-1856. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S90092

- Lei Z, Cao Z, Yang Z, Ao M, Jin W, Yu L. Rosehip Oil Promotes Excisional Wound Healing by Accelerating the Phenotypic Transition of Macrophages. Planta Medica. 2019;85(7):563-569. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0725-8456

- Andersson U, Berger K, Högberg A, Landin-Olsson M, Holm C. Effects of rose hip intake on risk markers of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease: a randomized, double-blind, cross-over investigation in obese persons. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2011;66(5):585-590. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2011.203

- Andaç Öztürk S, Yaman M. Investigation of bioaccessibility of vitamin C in various fruits and vegetables under in vitro gastrointestinal digestion system. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization. Published online June 13, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11694-022-01486-z

- Thomsen M. Phytotherapy Desk Reference. 6th ed. Aeon Books; 2022.

- Miljković VM, Nikolić L, Mrmošanin J, et al. Chemical Profile and Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity of Rosa canina L. Dried Fruit Commercially Available in Serbia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024;25(5):2518. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25052518

- Gardenia. Rosa canina (Dog Rose). Gardenia.net. https://www.gardenia.net/plant/rosa-canina

- Royal Botanical Gardens Kew. Rosa canina L. | Plants of the World Online | Kew Science. Plants of the World Online. https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:731955-1

- Khela S. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Rosa canina. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Published May 30, 2012. Accessed August 28, 2025. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/203447/2765713

- Engels G, Brinckmann J. Dog Rose Hip – American Botanical Council. www.herbalgram.org. Published 2016. https://www.herbalgram.org/resources/herbalgram/issues/111/table-of-contents/hg111-herbpro-rosehip/

- Adamant A. Foraging Rose Hips (& Ways to Use Them). Practical Self Reliance. Published September 18, 2023. https://practicalselfreliance.com/rose-hips/

- Thompson T. How to grow and care for dog rose. BBC Gardeners World Magazine. Published 2025. https://www.gardenersworld.com/how-to/grow-plants/how-to-grow-and-care-for-dog-rose/