-

How does it feel?

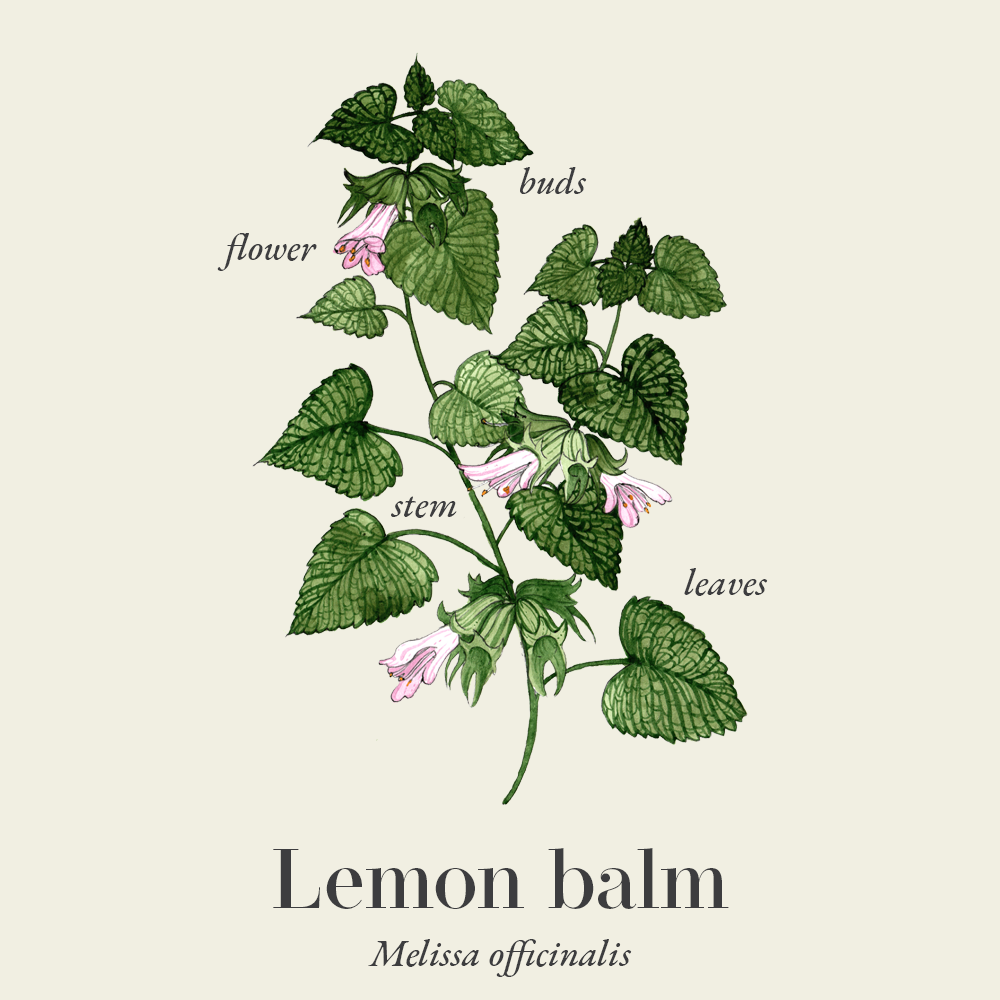

Lemon balm grows widely in gardens and makes a great plant for anyone to grow themselves, even in a window box. Look out for its characteristic light green leaves: picking and sniffing a leaf will tell you immediately you have the right plant. There is that wonderful aromatic lemony aroma. Chew a piece and the bright, citrusy taste comes through straightaway: the strong aromatic lemon flavour is combined with subtle hints of mint; the slight lemon acidity and tannic astringency combined with a real sweetness.

Lemon balm delivers its properties immediately. This is clearly a gentle, soothing yet uplifting remedy, acceptable to everyone from the very youngest of age.

-

What can I use it for?

Lemon balm is of particular use where a digestive upset is exacerbated by stress and anxiety. It is great for children, who may prefer the taste to chamomile.

Lemon balm is of particular use where a digestive upset is exacerbated by stress and anxiety. It is great for children, who may prefer the taste to chamomile.This relaxant effect has also been useful where stress affects the chest and heart, with symptoms like palpitations and hyperventilation: these in turn may be associated with acid reflux, hiatus hernia, associated symptoms that can arise when the digestion is stressed.

Lemon balm tea also has a gentle lifting effect that can be very comforting in low moods. Indicated in anxiety, tension and mild-depression it also used for conditions characterised by nervous pain such as fibromyalgia but also in neuralgia and numbness (11).

A primary herb of the nervous system, lemon balm is an excellent herb of choice for stress and anxiety. Like chamomile, it can be used where nervous tension causes digestive symptoms such as indigestion, flatulence and IBS (11).

It is an effective vasodilator ad diaphoretic, which can be used to gently support circulation in the periphery. These actions are also well applied in the management of a fever (13).

Lemon balm essential oil, or highly concentrated extracts have demonstrated benefits in relieving the symptoms of oral herpes infections or cold sores. However this effect is unlikely to be found with the herb on its own.

-

Into the heart of lemon balm

Lemon balm is both sour and sweet, with aromatic and bitter qualities. Energetically, lemon balm is cooling, a classic action of a herb with sour/ sweet/ bitter taste qualities. A herb that has a dynamic sensory profile, that engages our nervous system on multiple levels.

Lemon balm is both sour and sweet, with aromatic and bitter qualities. Energetically, lemon balm is cooling, a classic action of a herb with sour/ sweet/ bitter taste qualities. A herb that has a dynamic sensory profile, that engages our nervous system on multiple levels.As a primary herb of the nervous system, lemon balm is an excellent herb of choice for stress and anxiety. Like chamomile, it can be used where nervous tension causes digestive symptoms such as indigestion, flatulence and IBS. However, it will be less appropriate where metabolic excess in the stomach is the cause of digestive problems. A herbalist would always assess the full picture of health to gain an understanding of the root cause and prescribe accordingly.

Lemon balm works well in a tense, ‘excited’ tissue state- this patient will often have a sharp, tense possibly irregular pulse, palpitations, raised blood pressure and brightly red or pink tongue. This symptom picture often indicates sympathetic nervous system (SNS) excess in a patient- often caused by prolonged exposure to stress (see ‘nervous system’ under ‘What practitioners say’ for more information on SNS excess).

As often found with aromatic herbs of the mint family, lemon balm improves mental clarity. All herbs with aromatic chemistry will have a direct effect on the emotional axis of the brain, due to the relationship between the parts of the brain that process smell and the part the processes emotions (the olfactory system and the limbic system).

Lemon balm is cold in the second degree by the Galenic classification; qualifying the heat of the stomach, aiding digestion; abating to the heat of a fever; and ‘to refresh the spirits almost suffocating’. A ‘relaxant’ which is less than sedative and unlikely to depress, yet able to create a sense of calm and uplift.

The blend of its powerful aromatic compounds and grounding cooling bitters are able to reassure the gentleness of its calming and cooling actions. A truly beautiful balance for one of the most reliably calming family remedies that can be safely used by anyone, with a flavour that is widely enjoyed by all ages.

In the Ayurvedic understanding, lemon balm is a wonderful cooling remedy for excess pitta. A great medhya herb, enhancing memory and circulation, excellent for disturbance of sadhaka pitta causing anxiety, fear of failure, low self-esteem and insomnia. It clears excess pitta from rasa and rakta dhatus, calming the heart and cooling heat in eyes and mutravahasrotas. Anulomana; a good remedy for stress related digestive problems.

-

Traditional uses

Lemon balm was originally one of the stand-by remedies for the home-management of fever. Many of its modern uses apply the same characteristics: safe, gently calming, vasodilatory (opening the peripheral blood circulation) and antispasmodic properties.

Lemon balm was originally one of the stand-by remedies for the home-management of fever. Many of its modern uses apply the same characteristics: safe, gently calming, vasodilatory (opening the peripheral blood circulation) and antispasmodic properties.Lemon balm was described by Culpepper as a herb that ‘causes the mind and heart to become merry and reviveth the heart’. This can be said to be applied to both the physical and emotional heart. Lemon balm is well-known for its uplifting effect which can be applied in depressive emotional states, lifting states of gloom and despair.

Lemon balm is also traditionally used to support fertility and has long been used in love potions for fertility and as an aphrodisiac. Lemon balm has a strong sexual connotation, especially for women who have experienced sexual trauma, believed to help reconnect with a sense of femininity, rebuilding a sense of integrity and wholeness.

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

Western energetics

-

What practitioners say

Digestive system

Lemon balm has carminative and antispasmodic properties and is indicated in flatulence, dyspepsia, spasms and generalised indigestion; particularly where this is exacerbated by anxiety and stress. It can be helpful for heartburn and indigestion, assisting the absorption of nutrients, particularly fatty foods (as with many herbs from the mint family).

Cardiovascular system

It is a gentle circulatory tonic that dilates the peripheral blood vessels, lowers high blood pressure and relieves stress-related symptoms such as palpitations or angina.

It is the effects of lemon balm on the sympathetic nervous system (see notes under ‘nervous system’ below) that produce its therapeutic effects on the heart, particularly where an increased heart rate and blood pressure are a result of sympathetic overactivity) (14).

Nervous system

Lemon balm is an important herb for the nervous system, particularly where there is sympathetic excess. The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) is a branch of the Automatic nervous system (ANS) that governs ‘stress hormones’ such as adrenaline and cortisol- which through periods of prolonged stress exposure lead to excessive sympathetic function.

The SNS controls blood pressure, pulse rate, gut motility and almost all of our internal organs, where ‘action and alertness’ are involved (13, 14).

Indicated in anxiety, tension and mild-depression, also in conditions characterised by nervous pain such as fibromyalgia but also in neuralgia and numbness.

Respiratory system

Used as a relaxant remedy for asthma and spasmodic coughs. A herb that is often used during viral respiratory infections to manage fever symptoms, by increasing sweat production and reducing a viral fever (11).

Immune system

Lemon balm is an effective treatment for herpes simplex virus (cold sores). The essential oil (diluted) or cream of lemon balm can be applied to the affected area (10). Taken as a tea or tincture orally, lemon balm may also help with the virus systemically but for topical treatment of cold sores, an essential oil-based preparation must be used.

Metabolism

Lemon balm looks to be a promising long-term complement to dietary control of the metabolic syndrome that often merges into late onset diabetes (7).

-

Research

Nervous system

Nervous systemIn modern support of lemon balm’s traditional reputation, 55 sufferers from regular bouts of palpitation who took 14- day of treatment with 500 mg of lyophilized aqueous extract of lemon balm leaves, in comparison to the placebo reduced frequency of their palpitation episodes and significantly reduced anxiety (1). Two double-blind crossover studies evaluated the mood-affecting and cognitive effects of a standardised lemon balm preparation administered in a beverage and in yoghurt. In each study, a cohort of healthy young adults’ self-rated aspects of mood were measured before and after a multi-tasking framework administered one hour and three hours following one of four treatments. Both active lemon balm treatments were generally associated with improvements in mood and/or cognitive performance (2).

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, balanced crossover experiment, 18 healthy volunteers received two separate single doses of a standardized lemon balm extract (300 mg, 600 mg) and a placebo, on separate days separated by a 7-day washout period. 600 mg of lemon balm ameliorated the negative mood effects of a laboratory stress test, with significantly increased self-ratings of calmness and reduced self-ratings of alertness. In addition, a significant increase in the speed of mathematical processing, with no reduction in accuracy, was observed after ingestion of the 300-mg dose (3).

In an earlier study 20 healthy, young participants received single doses of 600, 1000, and 1600 mg of dried lemon balm, or a matching placebo, at 7-day intervals. Cognitive performance and mood were assessed just before and up to 6 hours after, using an established computerised assessment battery and visual analogue scales. The most notable cognitive and mood effects were for the highest (1600 mg) dose: it improved memory performance and increased ‘calmness’ up to 6 hours after taking the herb. However, improved memory task performance and visual information- processing increased with decreasing dose (4).

Inhaling the essential oil of lemon balm has also been shown to reduce agitation, in this case in a double blind controlled study among care home residents with severe dementia (5).

In Germany, an analysis of compounds in lemon balm showed significant central nervous system calming activity. Germans made reference to psychological- autonomic imbalance, such as that which is produces symptoms of excitability, restlessness, headaches and palpitations; in a double blind clinical trial demonstrated a clear clinical improvement in participants symptoms (13).

Cardiovascular system

In an other research direction, randomized, placebo-controlled trial with 62 patients received either 700 mg/day of lemon balm capsules or placebo for 12 weeks. Those taking the herb found significant differences in serum blood sugar, HbA1c, pancreatic β-cell activity lipid profile, inflammatory markers, and systolic blood pressure (6). The same team had earlier shown promising benefits on other markers of cardiovascular health relevant to the management of diabetes (7).

Similar cardiovascular benefits were found among patients with chronic angina (8). 3 g daily over 8 weeks of lemon balm also reduced depression, anxiety, stress, and sleeplessness in this group of patients (9).

Immune system

The reputation of concentrated lemon balm extracts in treating oral herpes simplex virus were tested in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised trial with a standardised lemon balm cream (a dried 70:1 extract of lemon balm leaves) with 66 patients with at least four episodes per year or with placebo. The cream was applied to the affected area four times daily over five days. A combined symptom score of the values for complaints, at day 2 of therapy was formed as the primary target parameter. There was a significant difference in size of affected area and number of blisters in those taking the lemon balm (10).

Pharmacology

Lemon balm contains high quantities of rosmarinic acid, a compound also found in tulsi, sage and, of course, rosemary. This renowned chemical is thought to enhance the volume of the GABA neurotransmitter making it more bioavailable in the nervous system. It is thought to be the mechanism by which lemon balm induces feelings of calmness (12).

Lemon balms bee-attracting essential oils, replicate the nasonov pheromone which is given off by bees to help orient the worker bees back to the colony. The oils have well-studied effects on the oral herpes virus. Some of these oils are geranial and neral, b-caryophyllene, linalool, geraniol, nerol, citronellal further contributing to the digestive and calming effects too (12).

The monoterpenes in Lemonbalm have been found to have central nervous system calming effects. The volatile oils are responsible for the antiseptic activity (13).

-

Did you know?

The volatile oils have been closely investigated in Germany where the plant is the main ingredient of a popular medicine known as ‘Melissengeist’.

Additional information

-

Botanical description

Lemon balm is a member of the mint family native to Southern Europe, though now growing around the world. It will grow in natural wasteland at a range of different elevations and environmental conditions. The leaves produce a characteristically ‘lemony’ scent when rubbed. The plant can grow to a variety of heights, from just a few inches to a few meters, depending upon the space it has to spread. The leaves are petiolate, decussate, ovate, dentate, and arise from erect square stems, branching little at first, but much more at flowering. The small white flowers grow in cymes of 3-5 in the upper leaf axils: they are typically labiate ie. two-lipped, with 4 curved stamens and a 5-toothed calyx. The roots do not ‘creep’ in stolons like other mints.

-

Common names

- Melissa

- Bee balm

- Honeyplant (Eng)

- Mélisse (Fr)

- Toronjil (Sp)

- Zitronenmelisse (Ger)

-

Safety

Lemon balm is safe to use in pregnancy and breastfeeding

-

Interactions

Moderate: Taking lemon balm seems to decrease how well thyroid hormone works in the body. Taking lemon balm with thyroid hormone might decrease the effects of the thyroid hormone. Use cautiously or under professional guidance.

-

Contraindications

None known

-

Preparations

- Fresh herb tea

- Dried herb tea

- Tincture

- Essential oil

- Cream

- Hydrolat

- Spagyric tincture

-

Dosage

- Capsules: Take 300 to 500 mg dried lemon balm, 3 times daily or as needed.

- Tea: 3g – 12g grams (1/4 to 1 tsp.) of dried lemon balm herb in hot water. Steep and drink up to 4 times daily. For fresh herb – use 1x handful infused in hot water

- Tincture (1:5 in 40%): Take 2-6ml three times daily.

- Topical: Apply topical cream to affected area, 3 times daily or as directed

-

Plant parts used

- Leaf

- Flower

-

Constituents

- Rosmarinic acid and other hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives (eg. caffeic and chlorogenic acids).

- Volatile oil: monoterpenes, citral, geraniol and neral, b-caryophyllene, linalool, geraniol, nerol, citronellal

- Tannins

- Flavonoids principally luteolin derivatives and apigenin

- Triterpenes (ursolic and oleanolic acid).

- Caffeic acid

- Tannins

- Bitters

-

Habitat

Lemon balm is a member of the mint family native to Southern Europe, though now growing around the world. It will grow in natural wasteland at a range of different elevations and environmental conditions.

-

Sustainability

Find FairWild certified producers for lemon balm. Although classified as a protected species in Croatia, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) European Red List of Medicinal Plants assigns M. officinalis to the conservation category of least concern, meaning that the species is not threatened in Europe.

However, the situation is different in parts of Asia. In Iran, wild M. officinalis is reportedly threatened due to habitat destruction, land use changes, and overharvesting (15).

-

Quality control

Melissa has tiny levels of essential oils (hence the expense), it loses much of its delightful smell on drying, and doesn’t fare much better as a tincture. Lemon balm is a herb that many herbalists can agree is best used fresh. Using fresh leaves picked from the garden for tea or tinctured from fresh in a good sweet brandy.

-

How to grow

For best results, sow indoors in spring. Scatter the seeds on the surface (or carefully place in plug trays), cover with a very thin layer of soil and tamp down. It can take several weeks to germinate so be patient and keep the soil moist (12).

Lemon balm is susceptible to frost damage, especially when young, so avoid planting out until you are confident that last frost has been and gone. Or – if you do plant out early – keep an eye on the weather forecast and cover the plants with fleece if there is a risk of overnight frost.

Once established, lemonbalm may become prolific, so it is best kept in containers or small beds.

-

Recipe

‘Let there be joy’ Tea

‘Let there be joy’ TeaNot all of life’s experiences are easy, but this tea will help you digest them with this blend of ‘instant-happiness-herbs’.

Ingredients:

- Lemon balm 3g

- Limeflower 3g

- Lavender flower 2g

- Rosemary leaf 1g

- St John’s wort flowering top 1g

- Rose water 1 tsp per cup

- Honey – a dash per cup

This will serve 2 cups of happiness.

Method:

- Put all of the ingredients in a pot (except for the rose water and honey).

- Add 500ml (18fl oz) freshly boiled filtered water. Leave to steep for 10–15 minutes, then strain.

- Add the rose water and honey to taste, then sip for joy.

Melissa’s magic tea

Growing in almost every garden, melissa officinalis, also commonly known as lemon balm, is not only popular with bees but is an excellent herb for children. Why not make a large pot of tea for the whole family and enjoy our Melissa’s magic tea whenever you want to relax and raise your spirits.

Ingredients:

- Fresh lemon balm leaf 2 sprigs (the top 8cm/31/4in with 4–6 leaves) This will serve 1 cup of magical tea.

Method:

- Put the lemon balm in a cup. Add 250ml (9fl oz) freshly boiled filtered water.

- Leave to steep for a few minutes and enjoy with the leaves still in your cup.

- Pick fresh lemon balm before it flowers for the sweetest cup. If you don’t have access to any fresh lemon balm then use 1 tsp of good quality dry leaf.

These recipes are from Cleanse, Nurture, Restore by Sebastian Pole

-

References

- Alijaniha F, Naseri M, Afsharypuor S, et al. (2015) Heart palpitation relief with Melissa officinalis leaf extract: double blind, randomized, placebo controlled trial of efficacy and safety. J Ethnopharmacol. 164: 378-384

- Scholey A, Gibbs A, Neale C, et al. (2014) Anti-stress effects of lemon balm-containing foods. Nutrients. 6(11): 4805-4821

- Kennedy DO, Little W, Scholey AB. (2004) Attenuation of laboratory-induced stress in humans after acute administration of Melissa officinalis (Lemon Balm). Psychosom Med. 66(4): 607-613

- Kennedy DO, Wake G, Savelev S, et al. (2003) Modulation of mood and cognitive performance following acute administration of single doses of Melissa officinalis (Lemon balm) with human CNS nicotinic and muscarinic receptor- binding properties. Neuropsychopharmacology. 28(10): 1871-1881

- Ballard CG, O'Brien JT, Reichelt K, Perry EK. (2002) Aromatherapy as a safe and effective treatment for the management of agitation in severe dementia: the results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial with Melissa. J Clin Psychiatry. 63(7): 553-558

- Asadi A, Shidfar F, Safari M, et al. (2019) Efficacy of Melissa officinalis L. (lemon balm) extract on glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes: A randomized, double-blind, clinical trial. Phytother Res. 33(3): 651-659

- Asadi A, Shidfar F, Safari M, et al. (2018) Safety and efficacy of Melissa officinalis (lemon balm) on ApoA-I, Apo B, lipid ratio and ICAM-1 in type 2 diabetes patients: A randomized, double-blinded clinical trial. Complement Ther Med. 40: 83-88

- Javid AZ, Haybar H, Dehghan P, et al. (2018) The effects of Melissa officinalis (lemon balm) in chronic stable angina on serum biomarkers of oxidative stress, inflammation and lipid profile. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 27(4): 785-791

- Haybar H, Javid AZ, Haghighizadeh MH, et al. (2018) The effects of Melissa officinalis supplementation on depression, anxiety, stress, and sleep disorder in patients with chronic stable angina. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 26: 47-52

- Koytchev R, Alken RG, Dundarov S. (1999). Balm mint extract (Lo-701) for topical treatment of recurring herpes labialis. Phytomedicine. 6(4): 225-230

- E. Brooke (1998). A Womans Book of Herbs. The Woman’s Press Ltd. Berkshire, England.

- Earthsong Seeds. (n.d.). Lemon Balm. [online] Available at: https://earthsongseeds.co.uk/shop/seeds/lemon-balm/ [Accessed 14 Jul. 2022].

- Mills, S.Y. (1993). The essential book of herbal medicine. Editorial: Penguin.

- Wood, M. (2004). The practice of traditional western herbalism : basic doctrine, energetics, and classification. Berkeley, Calif.: North Atlantic Books, Cop.

- www.herbalgram.org. (n.d.). Lemon Balm – American Botanical Council. [online] Available at: https://www.herbalgram.org/resources/herbalgram/issues/115/table-of-contents/hg115-herbprofile/.

Lemon balm is of particular use where a digestive upset is exacerbated by stress and anxiety. It is great for children, who may prefer the taste to chamomile.

Lemon balm is of particular use where a digestive upset is exacerbated by stress and anxiety. It is great for children, who may prefer the taste to chamomile. Lemon balm is both sour and sweet, with aromatic and bitter qualities. Energetically, lemon balm is cooling, a classic action of a herb with sour/ sweet/ bitter taste qualities. A herb that has a dynamic sensory profile, that engages our nervous system on multiple levels.

Lemon balm is both sour and sweet, with aromatic and bitter qualities. Energetically, lemon balm is cooling, a classic action of a herb with sour/ sweet/ bitter taste qualities. A herb that has a dynamic sensory profile, that engages our nervous system on multiple levels. Lemon balm was originally one of the stand-by remedies for the home-management of fever. Many of its modern uses apply the same characteristics: safe, gently calming, vasodilatory (opening the peripheral blood circulation) and antispasmodic properties.

Lemon balm was originally one of the stand-by remedies for the home-management of fever. Many of its modern uses apply the same characteristics: safe, gently calming, vasodilatory (opening the peripheral blood circulation) and antispasmodic properties.

Nervous system

Nervous system

‘Let there be joy’ Tea

‘Let there be joy’ Tea