-

Herb overview

Safety

Generally safe and well tolerated

Sustainability

Low risk/Green

FairWild certified sources availableKey constituents

Iridoid glycosides

Flavonoids

TanninsQuality

Native across Europe and parts of north Africa

Predominantly wild harvested

Low adulteration/ contamination risksKey actions

Lymphatic

Diuretic

Depurative

Anti-inflammatoryKey indications

Eczema

Rheumatism

Infection

AcneKey energetics

Cooling

MoisteningPreperation and dosage

Aerial parts

Succus: 5–15 ml per day

Tincture (1:5| 25%): Take between 12–24 ml daily

-

How does it feel?

A cold infusion made using spring water and freshly foraged cleavers is one of the finest tastes of spring. Cleavers deliver a crisp, clean cucumber-like taste which is a delight to drink. When making an infusion with cleavers, the fresh herb is always best due to its high water content, and much of the herb mass and the medicinal potency is lost on drying. The tincture of cleavers is similar to the taste — with smooth and grassy tones.

-

Into the heart of cleavers

Energetically, cleavers are cooling and demulcent. Cleavers improves the movement and flow in the lymphatic system, reducing stagnation in the tissues. This action allows for better removal of toxins and, therefore, it also allays inflammation and restores balanced function in tissues throughout the body.

The removal of toxins and congestion produces a systemic cooling action. This indicates cleavers in the treatment of hot, inflamed or chronic inflammatory disorders where a cooling and decongestant action would be beneficial — such as fluid retention, excess phlegm and rheumatic conditions (4).

-

What practitioners say

Immune system

Immune systemCleavers are a primary herb of the lymphatic system, an integral part of the immune system responsible for fluid balance. This makes cleavers a highly useful medicine for almost all treatment protocols, due to the importance of these functions in holistic herbalism. Part of the lymphatic system’s function is to transport white blood cells (immune cells) around the body. Therefore, when working to support the immune system, it is wise to also consider lymphatic support (1,3).

Improving the function of the lymphatic system assists with the removal of toxins and reduces congestion anywhere in the body. Cleavers also enhance the immune function, increasing one’s resilience to illness. Cleavers can directly enhance the immune response by increasing the production of key immune cells including splenocytes, activating natural killer (NK) activity and increasing cytokines (7).

Cleavers may be prescribed in the treatment of conditions affecting the lymphatic system, such as lymphoedema, mumps, tonsilitis, glandular fever or fluid retention, which is often observed in systemic inflammatory conditions (1,4).

Cancer

Cleavers may be used by herbalists as part of an integrated approach for cancer patients and for those in remission. It offers many benefits to the immune system, whilst supporting cellular detoxification through improved lymphatic drainage. Cleavers are rich in antioxidant compounds, such as flavonoids and tannins. This makes them an excellent support to help maintain cellular health and avoid damage caused by free radicals (8,9). However, for treating such serious conditions it is advised to work with a medical herbalist alongside doctors and oncologists, to ensure all healthcare providers are aware of potential herb–drug interactions.

Urinary system

Cleavers has a gentle yet powerful, soothing diuretic action that is used to increase the flow of urine. Due to these actions, cleavers would be appropriate for use where there is irritation and inflammation in the bladder, urethra, or vas deferens in the testes (8,10).

Cleavers are a valuable remedy for cystitis, benign prostatic hyperplasia, prostatitis, epididymitis, urethritis, chronic UTIs, and interstitial cystitis. They are used in combination with soothing urinary demulcents such as corn silk (Zea mays) and marshmallow leaf (Althaea officinalis) (8,9,11).

The mechanism of action for cleavers as a demulcent healer of the mucous membranes, such as those in the urinary tract, is due to the presence of silica, which strengthens weak connective tissue and improves its structure and function (10).

Skin health

Cleavers should always be considered for conditions of the skin, particularly those of a dry nature, such as psoriasis or dry eczema. It can be taken internally to support the underlying inflammation and to support the elimination of cellular toxins and waste products (1,2).

A herbalist’s approach to the treatment of inflammatory skin conditions will usually include support for the systems of elimination, such as the hepatic (liver) and renal (kidney) systems. This is because, in many cases, these systems are observed to be under-functioning.

This poor eliminatory function is understood to result in an excess of toxins in circulation. As a system of elimination, when the liver, kidneys and lymphatic system are overburdened, excess toxicity may be processed via the skin. As cleavers supports all of these systems, it is an invaluable herb to include in any prescription for an individual with a chronic skin condition (9,11).

Nervous system

Cleavers are also well referenced as a herb for the nervous system. Matthew Wood specifies indications for cleavers as “nervousness, sympathetic excess, skin irritability/ itchiness, an unsettled feeling, insatiability and nervous irritability”. Cleavers can be used alongside other nervine herbs such as oat straw (Avena sativa), lemon balm (Melissa officinalis) or vervain (Verbena officinalis) for these presentations (12,13).

-

Cleavers research

Cleavers (Galium aperine) There is a surprising lack of research for cleavers, despite its long and successful history of use in herbal medicine. Some available in vitro studies showing the mechanism of action using extracts and certain compounds in cleavers have, however, been included. Clinical trials in human subjects are the most relevant and reliable form of evidence. Most clinical trials are carried out using ‘whole plant’ extracts that better validate the effects of a full spectrum of active herbal compounds.

Phytochemical profiles and in vitro immunomodulatory activity of ethanolic extracts from Galium aparine L.

In this in vitro study, the chemical composition and immunomodulatory activities of cleavers ethanolic extracts were analysed. The extracts were obtained at three different strengths by maceration with 20%, 60% or 96% ethanol. All of the extracts showed that they helped stimulate the transformational activity of immunocompetent blood cells (cells that mediate the immune response). Overall, the 96% ethanol extract was shown to be most active when supporting immune response (14).

Evaluation of diverse antioxidant activities of Galium aparine spectrochimica acta part A: molecular and biomolecular spectroscopy

This study investigated the immunostimulatory activity and antioxidant potential of a raw infusion and different bioactive fractions. It was shown that cleavers caused significant immunostimulatory and antioxidant scavenging activities with the strongest effect seen in the aqueous fraction. The butanol fraction contained the highest phenolic and flavonoid content. The study concluded that the antioxidant activity could indicate cleavers in the treatment of a variety of oxidative stress-related diseases, such as cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases and diabetes (15).

Effects of Galium aparine extract on the cell viability, cell cycle and cell death in breast cancer cell lines

This in vitro study was conducted on methanolic extracts of cleavers to evaluate its activity on human breast cancer cells and healthy breast epithelial cells. Galium aparine was tested at various concentrations and time points (up to 72 hours) and the cytotoxicity, cell cycle effects and cell death pathways were evaluated. The results showed that the extract induced apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells (human breast cancer, triple negative), necrosis in MCF-7 cells (human breast cancer, oestrogen receptor positive) and G1 cell cycle arrest after 72 hours of treatment.

Results show that the extract was cytotoxic against the cancer cells, killing cancer cells yet sparing normal healthy cells. These findings support the therapeutic potential of cleavers as an adjunct to cancer care. More research is required to evaluate whether these results translate into humans (19).

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

-

What can I use cleavers for?

Cleavers (Galium aperine) Cleavers is a spring cleansing medicine. The herb supports the lymphatic system and assists with clearing congestion, such as with spring colds. They can be used as a daily tonic throughout spring to clear stagnation built up throughout the winter. This medicine is safe for all the family and is best used as a fresh herb, foraged in early to mid spring (1).

Cleavers directly support immune function by promoting lymphatic drainage and can be used to help reduce the symptoms of seasonal viruses and bacterial infections (2). By enhancing lymphatic drainage cleavers helps to reduce congestion in the tissues and support microcirculation, aiding in the removal of metabolic waste as well as delivering essential nutrients throughout the body.

The anti-inflammatory and lymphatic qualities of cleavers are effective in supporting conditions of the upper respiratory tract by reducing swelling and resolving congestion. In promoting effective lymphatic function, cleavers helps to reduce mucus build up and breathing difficulties (3). Cleavers supports chronic skin conditions such as eczema, acne, psoriasis through its cleansing and detoxifying properties (1,3).

The season to harvest cleavers is short, and as they are best used fresh, a great way to use the herb is to make a succus (or juice), which can then be frozen into ice trays for extended use (see below for instructions).

-

Did you know?

Cleavers belongs to the same family as coffee. The seeds of cleavers can be roasted and used as a coffee substitute. They contain small amounts of caffeine and are easily foraged in abundance.

-

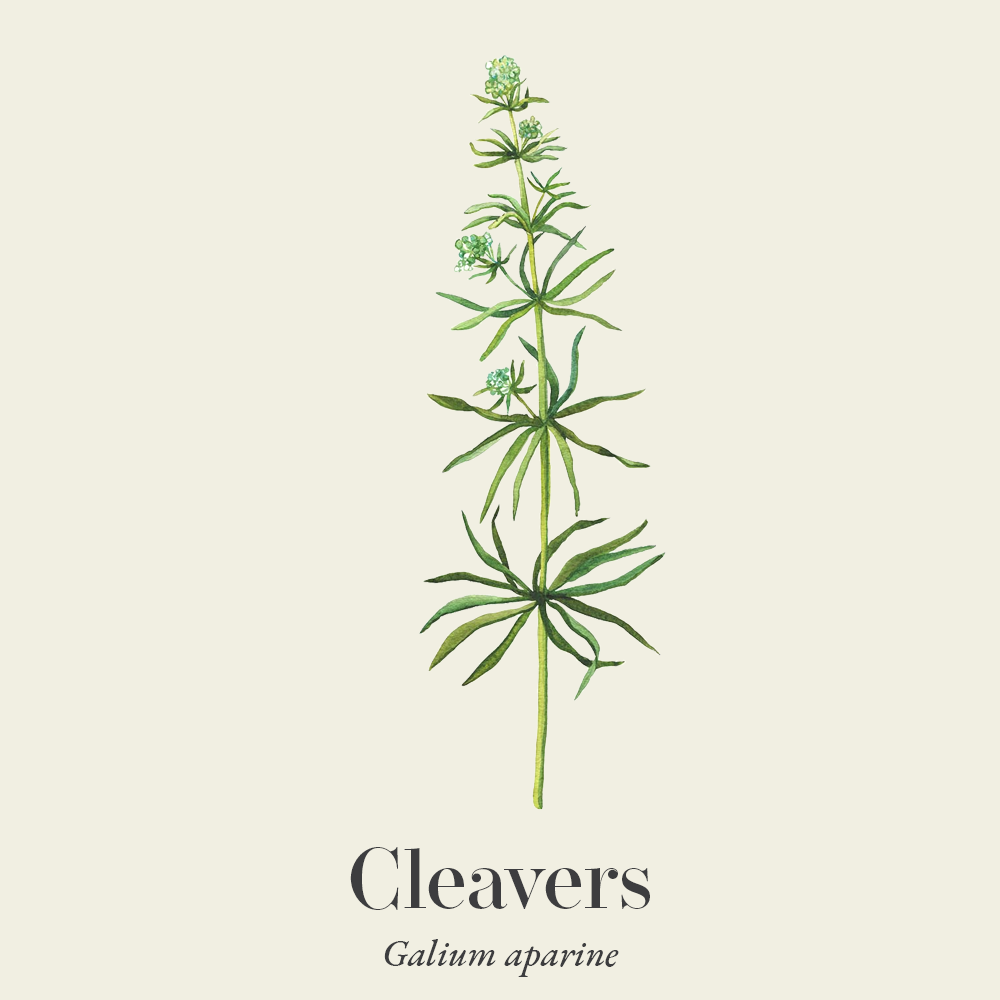

Botanical description

Cleavers are well known for their sticky leaves and stems. They consist of weak, sprawling stems, of up to 1 m (39 inches) long. They bear whorls of 6–8 mm long, slender green leaves with a prominent central vein.

Tiny greenish-white flowers are borne in branching clusters between May to August and develop into round, green (later brown/purple) fruits between 3–5 mm in diameter.

Stems, leaves and seed have stiff hooked hairs and are sticky or velcro like (3).

-

Common names

- Clivers

- Goosegrass

- Sticky willy

- Sticky weed

- Hedgeriff

-

Habitat

Cleavers are widespread and native across the United Kingdom, Europe and parts of north Africa. It can be found in a range of habitats including hedgerows, cultivated land, riverbanks, shingle, waste ground and woodland edges (18,19).

-

How to grow cleavers

Cleavers are commonly thought of as weeds. They are extremely easy to grow and sometimes can become a little over-populated in the garden. It’s worth noting that they will self seed easily and start popping up. Making medicine as fresh cleavers cold infusions (recipe above) helps to control the abundant populations.

Cleavers prefer a loose moist leafy soil but can tolerate some dry soil. Seeds are best sown outside directly into the garden soil as soon as the seed is ripe in late summer. The seed can also be sown in spring, though it may be very slow to germinate (22).

-

Herbal preparation of cleavers

- Fresh herb

- Hot or colds infusion

- Succus

- Tincture

- Fluid extract

-

Plant parts used

Aerial parts

-

Dosage

- Tincture (ratio 1:5| 25%): Take between 4–8ml three times a day.

- Fluid extract (1:1 | %): Take between 2–4ml in a little water three times a day.

- Infusion/decoction: Cleavers can be made into a hot or cold infusion by infusing around a handful of fresh herb or 2–3tsp of dried herb in either a pint of hot or cold water. Cold water infusions should be infused for between 24–48 hours. Hot infusions should be infused for up to 15 minutes. Strain and drink up to three times daily.

- Succus: The fresh juice of cleavers can also be frozen in ice cubes. Take between 5–15ml per day (3).

-

Constituents

- Phenolic acid: Caffeic; p- coumarin, gallic, p-hydroxybenzoic, salicylic, citric

- Coumarins

- Iridoid glucosides: Monotropein, asperuloside, rubichloric acid and aucubin

- Tannins: Up to 5% of the condensed type

- Phenols

- Flavonoids: Quercetin, hesperidin, luteolin (3)

-

Cleavers recipe

Cleavers cold infusion

Ingredients

- Cleavers

- Spring water

How to make a cleavers cold infusion

- Simply harvest a handful of fresh cleavers in spring.

- Chop them up a little to open up the surface for a deeper medicine or simply place into a pint glass or jug of spring water.

- Infuse the cleavers in the refrigerator for between 24–48 hours.

- Then pour off the refreshing cold infusion into a clean glass and drink freely throughout the day.

-

Safety

There is a lack of reliable data for the safety of cleavers during pregnancy and breastfeeding. It is advised to consult a medical herbalist for further guidance in these instances (1,2,3,17).

-

Interactions

Cleavers has strong diuretic properties, and should, therefore, be used with caution by individuals with diabetes or other conditions where fluid balance is controlled using medications (1,2,3,17).

-

Contraindications

None known (1,2,3,17)

-

Sustainability status of cleavers

According to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Plants Status cleavers are classified as ‘least concern’ due to its widespread distribution, stable populations and no major threats (20). Cleavers grow abundantly in the hedgerows in the spring and, as such, are not considered at risk or threatened (21).

Habitat loss and over-harvesting from the wild are two of the biggest threats faced by medicinal plant species. There are an increasing number of well-known herbal medicines at risk of extinction. We must, therefore, ensure that we source our medicines with sustainability in mind.

The herb supplement industry is growing at a rapid rate and until recent years a vast majority of medicinal plant produce in global trade was of unknown origin. There are some very real and urgent issues surrounding sustainability in the herb industry. These include environmental factors that affect the medicinal viability of herbs, the safety of the habitats that they are taken from, as well as the welfare of workers in the trade.

The botanical supply chain efforts for improved visibility (transparency and traceability) into verifiably sustainable production sites around the world is now certificated through the emergence of credible international voluntary sustainability standards (VSS).

Read our article on Herbal quality & safety: What to know before you buy and Sustainable sourcing of herbs to learn more about what to look for and questions to ask suppliers about sustainability.

-

Quality control

Cleavers may be harvested just before and as they begin to flower, and throughout their short flowering period. Once they begin to go to seed, they are no longer ideal for medicine making.

The fresh herb is always best with cleavers due to its high water content. Much of the herb mass is lost during drying. A fluid extract is typically made using fresh herb, rather than dried. However, the gold standard for this plant is used fresh or as succus (juice) made in spring. The succus can be poured into ice cube trays and frozen for later use (21).

Herbal medicines are often very safe to take; however, their safety and efficacy can be jeopardised by quality issues. So, it is important to buy herbal medicines from a reputable supplier, from sources known to test their herbs to ensure there is no contamination, adulteration or substitution with incorrect plant matter, as well as ensuring that recognised marker compounds are at appropriate levels in the herbs.

Some important quality assurances to look for are certified organic labelling, the correct scientific/botanical name, and the availability of information from the supplier about ingredient origins. A supplier should be able to tell you where the herbs have come from, what contaminants are not in the herb, and what the primary compounds are.

-

References

- Mcintyre A. Complete Herbal Tutor : The Definitive Guide to the Principles and Practices of Herbal Medicine (Second Edition). Aeon Books Limited; 2019.

- Thomsen M. Phytotherapy Desk Reference. 6th ed. Aeon Books; 2022.

- Fisher C. Materia Medica of Western Herbs. Aeon Books; 2018.

- Holmes P. The Energetics of Western Herbs . Snow lotus press; 2020.

- Grieve M. A Modern Herbal. Tiger Books International; 1994.

- King J, Wickes Felter H, Lloyd JU. King’s American Dispensatory. Ohio Valley Co; 1909.

- Lee S, Park S, Park H. Immuno-Enhancing Effects of Galium aparine L. in Cyclophosphamide-Induced Immunosuppressed Animal Models. Nutrients. 2024;16(5):597-597. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16050597

- Menzies-Trull C. Herbal Medicine Keys to Physiomedicalism Including Pharmacopoeia. Faculty Of Physiomedical Herbal Medicine (Fphm; 2013.

- Bone K, Mills S. Principles and Practice of Phytotherapy: Modern Herbal Medicine. 2nd ed. Edinburgh Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier; 2013.

- Brooke E. A Woman’s Book of Herbs. Aeon Books; 2018.

- Hoffmann D. Medical Herbalism : The Science and Practice of Herbal Medicine. Healing Arts Press; 2003.

- Wood M. The Practice of Traditional Western Herbalism. North Atlantic Books; 2013.

- Easley T, Horne SH. The Modern Herbal Dispensatory: A Medicine-Making Guide. North Atlantic Books; 2016.

- Ilina T, Kashpur N, Granica S, et al. Phytochemical Profiles and In Vitro Immunomodulatory Activity of Ethanolic Extracts from Galium aparine L. Plants. 2019;8(12):541. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants8120541

- Bokhari J, Khan MR, Shabbir M, Rashid U, Jan S, Zai JA. Evaluation of diverse antioxidant activities of Galium aparine. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2013;102:24-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2012.09.056

- Atmaca H, Bozkurt E, Cittan M, Dilek Tepe H. Effects of Galium aparine extract on the cell viability, cell cycle and cell death in breast cancer cell lines. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2016;186:305-310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2016.04.007

- Natural Medicines Database. Clivers. Therapeuticresearch.com. Published 2025. Accessed September 1, 2025. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/Data/ProMonographs/Clivers#safety

- The Wildlife Trust. Cleavers | The Wildlife Trusts. www.wildlifetrusts.org. https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/wildlife-explorer/wildflowers/cleavers

- Royal Botanical Gardens Kew. Galium aparine L. | Plants of the World Online | Kew Science. Plants of the World Online. https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:30007294-2

- Khela S. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Galium aparine. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Published May 30, 2012. Accessed September 26, 2022. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/203459/2765924

- James. Cleavers (Gallium aparine) Identification. Totally Wild UK. Published April 29, 2020. https://totallywilduk.co.uk/2020/04/29/identify-cleavers/

- RHS. Cleavers. www.rhs.org.uk. https://www.rhs.org.uk/weeds/cleavers