-

Herb overview

Safety

Avoid in pregnancy, lactation, anaemia or diarrhoea.

Sustainability

Low risk

Key constituents

Flavonoids

Phenolic acids

Tannins

NutrientsQuality

Northern hemisphere

Wild harvestedKey actions

Anti-inflammatory

Diuretic

Astringent

AntiproliferativeKey indications

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH)

Urinary tract infections

Diarrhoea

NocturiaKey energetics

Dry

Tonifying

Sour

AstringentPreperation and dosage

Aerial parts

5–9 g per day

-

How does it feel?

An infusion of the leaves and flowers smells sour with notes of citrus and a hint of apple. The taste is sour, sharp, and citrus which hits the back of the tongue and makes the cheeks pucker slightly. Despite the sharp sourness there are fruity hints of lemon, apple and pear, which makes it refreshing and uplifting to drink.

Initially the mouth feels watery and moist from the sourness, but this is quickly replaced by dryness from the astringent tannins. The sour taste indicates the presence of the polyphenols and flavonoids which account for the antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial activity (1,2).

The tannins are responsible for the dry, puckering sensation, and this drying effect extends across the mucous membranes throughout the digestive system. The sensations are grounding as it moves through the system. There is a sense of clarity and clearing as the mind feels sharper, clearer, brighter and slightly invigorated. Overall, rosebay willowherb makes a pleasant infusion which feels fresh, crisp, uplifting and mildly invigorating without being overly stimulating.

-

Into the heart of rosebay willowherb

Rosebay willowherb (Epilobium angustifolium) The polyphenols (flavonoids and phenolic acids) have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial activity (5). The tannins have astringent, anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative properties which can have a positive effect on prostate health (5). The mucilage constituents contribute to the soothing and demulcent action on mucous membranes, particularly the digestive and urinary tracts.

The diuretic action of rosebay willowherb increases the flow of urine from the kidneys through the urinary tract to the bladder, both aiding with excretion of metabolites during an infection, as well as facilitating the delivery of the herbs to get to where they are needed. The astringent and toning actions make this herb suited to tissue states of relaxation or atrophy (2).

The flower essence can help to release the tight muscles which arise from unexpressed anger (2). It provides grounding in times of major upheaval which can feel disorientating and confusing (6). It provides balance between willpower and anger, helping an individual to master wild and angry thoughts (2). In children, the flower essence will calm those that are overactive, wild and angry, and strengthen those who are timid and shy (2).

-

What practitioners say

Digestive system

Digestive systemRosebay willowherb is an astringent, tonic, emollient, and demulcent, which has a specific influence on the intestinal mucous membranes (9). It is useful in cases of acute or chronic diarrhoea, with an action similar to agrimony (Agrimonia eupatoria), herb robert (Geranium robertianum) and rose geranium (Pelargonium graveolens). It is a strong astringent and anti-inflammatory, soothing irritation throughout the gastrointestinal tract.

The tannins and anti-inflammatory constituents in rosebay willowherb help to soothe and restore normal function to the intestinal canal (9). It is a supportive herb to include in any formula where the individual needs a tonic effect on the mucous membranes of any part of the intestines. This could be from an acute bout of gastroenteritis or to heal ulceration in more chronic conditions such as coeliacs, ulcerative colitis, or Crohn’s disease. Read more about chronic conditions of the digestive system.

Urinary system

It is a specific remedy for prostate problems, including benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH), helping to shrink tissues, arrest cell proliferation and normalise urinary function (7). BPH is a non-cancerous increase in size of the prostate gland which surrounds the urethra — the tube that carries urine from the bladder out of the body (10). The Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC) concluded that, based on traditional and long-standing use, rosebay willowherb can be used by patients with BPH for the relief of lower urinary tract symptoms such as difficulty starting or frequent urination (10).

Clinical evidence suggests rosebay willowherb extract supplements can improve symptoms and quality of life in patients with BPH, by reducing urinary retention and urinary frequency, particularly nocturia (3). Laboratory research suggests that rosebay willowherb may influence prostate cell proliferation and exhibits notable anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antioxidant, antitumor, and antiandrogenic properties (5,10). These effects on the prostate and urethra improve micturition problems, supporting the use of rosebay willowherb in cases of BPH (3,5). You can read more about prostate health, including holistic and herbal solutions, here.

Although it is popular as a remedy for prostate function, it is also an effective astringent for toning the bladder in both men and women (7). The astringent and diuretic properties both tone and detoxify the urinary tract (7). It can be used in cases of urinary tract infections (UTI’s), incontinence or interstitial cystitis, combining well with other urinary herbs to specifically treat the individual symptoms. For ailments of the urinary system it is recommended to take herbal medicines as an infusion to increase the flow of urine from the kidneys through the urinary tract to the bladder. This provides a detoxification encouraging elimination and also making sure the herbs are delivered to the area where they’re required.

-

Rosebay willowherb research

Rosebay willowherb (Epilobium angustifolium) There is minimal clinical evidence to support the use of rosebay willowherb, and the indications for use are based on traditional use, in vitro research to determine the plant constituents, and the known actions of the constituents.

Epilobium angustifolium L. extract with high content in oenothein B on benign prostatic hyperplasia: A monocentric, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial

This clinical trial of 128 adult men with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) investigated rosebay willowherb extract (standardized to contain ≥ 15% oenothein B), in the form of gastric-resistant capsules (500 mg) daily for six months. The participants were randomly assigned to receive either the herb (N = 70) or placebo (N = 58). In the herb group, but not the placebo group, there was a significant decrease in urinary retention (measured by post-void residual), nocturia (night time urination), International Prostate Specific Score (IPSS) and quality of life. There were no adverse effects of the rosebay willowherb intake. The authors concluded that rosebay willowherb extract can be used in subjects with BPH, to improve their quality of life and general renal function (3).

Extracts of various species of Epilobium inhibit proliferation of human prostate cells

This in vitro study examined the antiproliferative effect of various Epilobium species on human prostatic epithelial cells. The extracts inhibited DNA synthesis in the prostate cells, inhibiting the progression of the cell cycle. The results suggest the herbal extracts inhibit proliferation of human prostate cells in vitro, providing some biological plausibility for the use of Epilobium extracts in BPH b (11).

Extracts from Epilobium sp. herbs induce apoptosis in human hormone-dependent prostate cancer cells by activating the mitochondrial pathway

This laboratory study explored the effect of rosebay willowherb extract on hormone-dependent prostate cancer cells. Exposure of the cancer cells to the extracts resulted in a significant increase in the level of apoptotic cells by up to 86.6%. The authors concluded that the herb extract was active against prostate cancer cells by increasing the apoptotic activity. This biological activity was attributed to the high phenolic concentration (oenothein B) of the plant material (12).

Evaluation of the therapeutic effect against benign prostatic hyperplasia and the active constituents from Epilobium angustifolium L.

This study provided both in vitro cell-line data and in vivo evidence using an animal model (rats). In vitro, the rosebay willowherb extracts demonstrated anti-BPH activity by inhibiting hyperplasia of benign prostatic epithelial cells, and suppressing prostate specific antigen (PSA) secretion by prostate epithelial cells. In vivo, rats with testosterone-induced BPH were orally administered the extracts at doses of 100-400 mg/kg for 28 days.

The extract exhibited therapeutic effects against the BPH by down-regulating of the androgen level, suppressing inflammatory cytokines (NF-κB) and alleviating the inflammatory responses and oxidative stress. The authors concluded from this pre-clinical study that rosebay willowherb extract has therapeutic potential against BPH, and the active compounds may be a candidate for the treatment of BPH (5).

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

-

What can I use rosebay willowherb for?

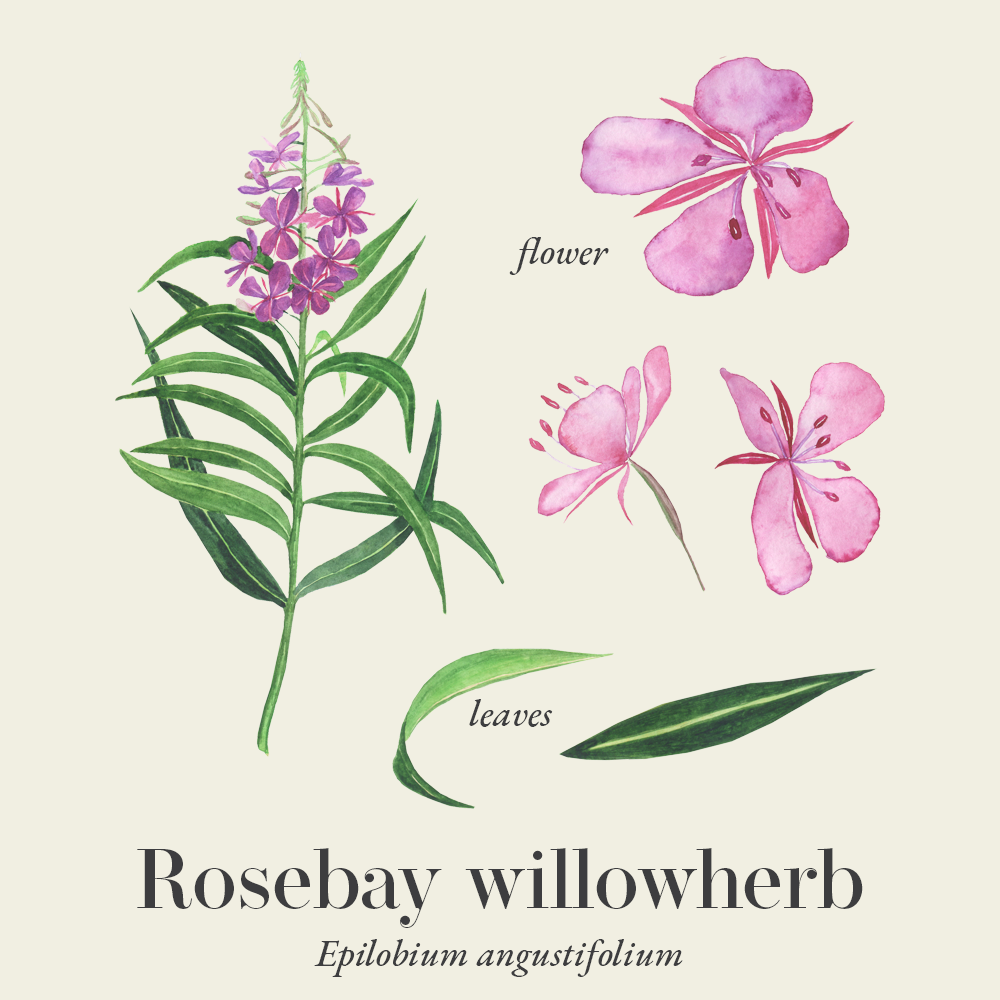

Rosebay willowherb (Epilobium angustifolium) The bright pink blooms appear prolifically in the wild spaces along riverbanks, roadsides and railways throughout July and August in the UK. The leaves and flowers of this abundant herb can be harvested throughout the later spring and summer.

It is a strong astringent, anti-inflammatory, and nutritive tonic, used to soothe irritation throughout the gastrointestinal tract. It is an effective remedy to be used in cases of acute or chronic diarrhoea, soothing and toning the mucous membranes and helping to promote a return to normal function (2). The astringent effect of the tannins throughout the digestive tract can heal wounds and ulcers, tighten the gut wall to improve absorption, and improve loose stools.

Rosebay willowherb is highly indicated for issues with the urinary system. Specifically, it is effective for treating prostate issues, particularly benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), as well as urinary tract infections, cystitis and kidney or bladder problems (2,3).

As a topical application, an infusion can be used as a wash for ulcers and wounds to dry up any discharges and aid healing. It can also be used as a mouth rinse or gargle for mouth ulcers, sore throats, tonsilitis or gum inflammation. A poultice made can be applied to burns, skin sores, swellings, boils and ulcers (3).

As a culinary herb, rosebay willowherb can be consumed as a vegetable, the young shoots eaten like asparagus by stripping the leaves and blanching (4). The leaves and flowers can also be added to salads in the spring, or used to make soup (see recipe below).

-

Did you know?

The genus name, Epilobium, comes from the Greek words epi (upon) and lobos (a pod) As the flowers stand up on the top of long thin pods like seed capsules, appearing like thick flower stems (4). The name willowherb comes from the willow-like shape of the leaves (4).

-

Botanical description

Rosebay willowherb (Chamaenerion angustifolium) or traditionally referred to as Epilobium angustifolium is a perennial flowering plant, abundant and widespread in the wild in the UK. The reddish-pink stems are usually simple, erect and smooth, growing to 0.5–2 metres, with scattered alternate leaves in a spiral arranged along the stem (15). The leaves are entire, narrowly lanceolate, and pinnately veined (15).

The inflorescence is a symmetrical terminal raceme in a striking spike of purple-pink flowers that bloom progressively from bottom to top (16). The flowers are 2 to 3 centimetres in diameter, slightly asymmetrical, with four magenta to pink petals (rose-purple) set in pink sepals (4,15).

The reddish-brown long seed pods split and curl open, bearing 300 to 400 minute brown seeds about per capsule, 80,000 per plant (17). The seeds have silky-downy hairs to aid wind dispersal and are easily spread by the wind, often becoming a weed and a dominant species on disturbed ground (7,17). Once established, the plants also spread extensively by underground roots and individual plants eventually form large patches (18).

-

Common names

- Fireweed

- Great willowherb

- Bombweed

- Bay willow

- Blooming willow

- Burntweed

- French willow

- French willowherb

- Herb wickopy

- Moose tongue

- Persian willow

- Pigweed

- Purple rocket

- Rose bay

- Rose elder

- Wickup

- Wickop

-

Habitat

The native range of rosebay willow is the Northern Hemisphere to Mexico and Morocco, growing primarily in the temperate biome (19).

Rosebay willowherb is often abundant in wet and slightly acidic soils in open fields, pastures, and particularly burnt lands (18). It quickly colonises open areas with little competition, such as the sites of forest fires and forest clearings (18). The name “fireweed” originates from the plant’s remarkable tendency to thrive in areas scorched by forest fires and other ecological disruptions, often becoming one of the first species to recolonise such landscapes (2).

Once seedlings are established, the plant quickly reproduces and covers the disturbed area via seeds and rhizomes (4). It will continue to grow and flower as long as there is open space and plenty of light, appearing conspicuously along riverbanks and railway verges from July to September.

-

How to grow rosebay willowherb

Rosebay willowherb is prolific in the wild, naturally occurring on a wide range of soils in open places such as verges or waste ground (16). It spreads easily so may need controlling if cultivated in a small space or home garden (16). During the spring and summer, before the seeds develop, if the stem is broken off, new side shoots will grow so leaves and flowers can be collected from the same plant several times during the year (7).

Propagation is by seed or division in spring or autumn, and does not require pruning, although deadheading will reduce self-seeding (16).

-

Herbal preparation of rosebay willowherb

- Infusion (Tea)

- Culinary

-

Plant parts used

Aerial parts – leaf and flower

-

Dosage

- Infusion/decoction: 1.5–3 g (1 teaspoon) dried herb per cup (250 ml) of boiling water, 2–3 times per day (7,10)

- Capsules: 500 mg extract per day (3)

- Topical: Wash using infusion, poultice or compress.

-

Constituents

- Flavonoids: Quercetin; kaempferol, rutin, myricetin, miquelianin (2,3,12)

- Phenolic acids: Gallic acid, ellagic acid, chlorogenic and caffeic acid (3,12)

- Tannins: Ellagitannins (oenothein A & B) (3,12)

- Mucilage (2,4)

- Nutrients: Vitamin C, carotenoids, calcium, magnesium, potassium (2)

-

Rosebay willowherb recipe

Springtime soup

The soup is packed with protein, vitamins and minerals from the fresh green herbs arriving in the spring. It is ideal to make with fresh spring herbs as they appear at the start of spring. It is nutritious and refreshing for the system after the stagnancy of winter.

Ingredients

- 25 g butter

- 2 onions – finely chopped

- 1 celeriac – peeled and diced

- 10 large handfuls of young nettle (Urtica dioica) leaves

- 4 handfuls of fresh rosebay willowherb leaves

- 4 handfuls of fresh lovage (Levisticum officinale) leaves

- 850 ml stock

- Juice of half a lemon (Citrus limonum)

- Optional: 1 teaspoon nutmeg (Myristica fragrans), ginger (Zingiber officinale), chilli (Capsicum minimum).

- Salt and pepper to taste

How to make a delicious spring soup with rosebay willowherb

- Melt the butter in a pan and gently sauté the onions and diced potatoes until soft.

- Add the chopped nettle, rosebay and lovage leaves and cook for one minute.

- Add the stock and bring to the boil, add your chosen spices and season with salt and pepper and leave to simmer for 20 minutes.

- Puree through a liquidiser and add the lemon juice.

- Serve hot or cold and garnish with chopped lovage leaves.

-

Safety

Rosebay willowherb is approved by the Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC) and is considered safe for long term use (10). A clinical trial using 500 mg/d of rosebay willowherb extract reported no adverse effect in 128 adult men with BPH, taken daily for six months (3).

No fertility data is available and use during pregnancy and when breastfeeding should only be under the guidance of a medical practitioner (10,13). Find a find qualified medical herbal professionals.

-

Interactions

None known (13)

-

Contraindications

Rosebay willowherb should be avoided, or only taken under the guidance of a medical herbalist in cases of constipation, iron deficiency anaemia or malnutrition (14). Prolonged use should be avoided due to the high tannin content which can inhibit mineral absorption (14).

-

Sustainability status of rosebay willowherb

The conservation status of rosebay willowherb was globally assessed in 2016 and given the status ranking of “least concern”, and does not appear on any regional red lists (20,21,23). A species is “least concern” when it has been evaluated against the criteria and does not qualify for critically endangered, endangered, vulnerable or near threatened (21). The species is widespread and abundant across North America, Europe and Asia, with stable subpopulations, and there are currently no major threats reported (20).

Rosebay willowherb is not listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act or by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), and does not appear on the United Plant Savers list of threatened species (23,24). Rosebay willowherb is not listed by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), with no legislation regarding trade of the species (22).

Habitat loss and over-harvesting from the wild are two of the biggest threats faced by medicinal plant species. There are an increasing number of well-known herbal medicines at risk of extinction. We must, therefore, ensure that we source our medicines with sustainability in mind.

The herb supplement industry is growing at a rapid rate and until recent years a vast majority of medicinal plant produce in global trade was of unknown origin. There are some very real and urgent issues surrounding sustainability in the herb industry. These include environmental factors that affect the medicinal viability of herbs, the safety of the habitats that they are taken from, as well as the welfare of workers in the trade.

The botanical supply chain efforts for improved visibility (transparency and traceability) into verifiably sustainable production sites around the world is now certificated through the emergence of credible international voluntary sustainability standards (VSS).

Read our articles on How to substitute endangered herbs, Herbal quality & safety: What to know before you buy and Sustainable sourcing of herbs to learn more about what to look for and questions to ask suppliers about sustainability.

-

Quality control

Herbal medicines are often very safe to take; however, their safety and efficacy can be jeopardised by quality issues. So, it is important to buy herbal medicines from a reputable supplier, from sources known to test their herbs to ensure there is no contamination, adulteration or substitution with incorrect plant matter, as well as ensuring that recognised marker compounds are at appropriate levels in the herbs.

Some important quality assurances to look for are certified organic labelling, the correct scientific/botanical name, and the availability of information from the supplier about ingredient origins. A supplier should be able to tell you where the herbs have come from, what contaminants are not in the herb, and what the primary compounds are.

-

References

- Maier K. Energetic Herbalism: A Guide to Sacred Plant Traditions Integrating Elements of Vitalism, Ayurveda, and Chinese Medicine. Chelsea Green Publishing; 2021.

- Wood M. The Earthwise Herbal Volume 2: A Complete Guide to New World Medicinal Plants. North Atlantic Books; 2008.

- Esposito C, Santarcangelo C, Masselli R, Buonomo G, Nicotra G, Insolia V, D’Avino M, Caruso G, Buonomo AR, Sacchi R, Sommella E. Epilobium angustifolium L. extract with high content in oenothein B on benign prostatic hyperplasia: A monocentric, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2021;138:111414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111414

- Grieve M, Leyel CF, Marshall M. A Modern Herbal. the Medicinal, Culinary, Cosmetic and Economic Properties, Cultivation and Folk-Lore of Herbs, Grasses, Fungi, Shrubs & Trees with All Their Modern Scientific Uses. Dover Publications; 1982.

- Deng L, Zong W, Tao X, Liu S, Feng Z, Lin Y, Liao Z, Chen M. Evaluation of the therapeutic effect against benign prostatic hyperplasia and the active constituents from Epilobium angustifolium L. Journal of ethnopharmacology. 2019;232:1-0. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2018.11.045

- Yorkshire Flower Essences. Rosebay willowherb. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://www.yorkshirefloweressences.com/products/rosebay-willowherb

- Burton-Seal J. and Seal M. Hedgerow Medicine: harvest and make your own herbal remedies. Merlin Unwin Books; 2014.

- Felter HW and Lloyd JU. Kings American Dispensary; 18th Edit; 1898. Reprinted on Henritttas Herbpages. Accessed September 29, 2025. https://www.henriettes-herb.com/eclectic/kings/epilobium.html

- Ellingwood F. The American Materia Medica, Therapeutics and Pharmacognosy; 1919. Reprinted on Henritttas Herbpages. Accessed September 29, 2025. https://www.henriettes-herb.com/eclectic/ellingwood/epilobium.html

- European Committee on Herbal Medicine Products (HMPC). Epilobii herba (Willow herb) – herbal medicinal product: European Medicines Agency. Accessed: 30 September, 2025. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/herbal/epilobii-herba

- Vitalone A, Guizzetti M, Costa LG, Tita B. Extracts of various species of Epilobium inhibit proliferation of human prostate cells. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2003;55(5):683-90. https://doi.org/10.1211/002235703765344603

- Stolarczyk M, Naruszewicz M, Kiss AK. Extracts from Epilobium sp. herbs induce apoptosis in human hormone-dependent prostate cancer cells by activating the mitochondrial pathway. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2013;65(7):1044-54. https://doi.org/10.1111/jphp.12063

- Natural Medicines Professional Database (NatMed). Therapeutic Research Centre. Fireweed Professional Monograph. Published 12 April, 2024. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/

- Brinker, FJ. Herbal Contraindications & Drug Interactions: Plus Herbal Adjuncts with Medicines. Eclectic Medical Publications, 2010.

- Francis-Baker T. Concise Foraging Guide. The Wildlife Trusts. Bloomsbury; 2021.

- Royal Horticultural Society. Chamaenerion angustifolium; rosebay willowherb. Accessed September 28, 2025. https://www.rhs.org.uk/plants/210071/chamaenerion-angustifolium/details

- Blamey M, Fitter R, Fitter AH. Wild Flowers of Britain and Ireland: 2Nd Edition. A & C Black; 2013.

- Kitchener GD, Stroh PA, Humphrey TA, Burkmar RJ, Pescott OL, Roy DB, & Walker, KJ. Chamaenerion angustifolium (L.) Scop. in BSBI Online Plant Atlas 2020. Accessed 28/09/2025. https://plantatlas2020.org/atlas/2cd4p9h.7fqgbm

- Royal Botanical Gardens Kew (RBGK). Epilobium angustifolium L. Plants of the Word Online (POWO). Accessed September 28, 2025. https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:92411-2

- Maiz-Tome L. Epilobium angustifolium. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016. Accessed 28 September 2025. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T164212A78457042.en.

- Cheffings C, Farrell L, (eds), Dines, T.D., Jones, R.A., Leach, S.J., McKean, D.R., Pearman, D.A., Preston, C.D., Rumsey, F.J., Taylor, I. The Vascular Plant Red Data List for Great Britain. Species Status No. 7. Joint National Conservation Committee. 2005. Accessed September 28, 2025. https://hub.jncc.gov.uk/assets/cc1e96f8-b105-4dd0-bd87-4a4f60449907

- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Accessed September 28, 2025. https://checklist.cites.org/#/en

- NatureServe explorer 2.0. Natureserve.org. Accessed September 28, 2025. https://explorer.natureserve.org/Taxon/ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.146640/Chamerion_angustifolium

- UpS list of herbs & analogs. United Plant Savers. Published May 14, 2021. Accessed September 28, 2025. https://unitedplantsavers.org/ups-list-of-herbs-analogs/